How tectonics, sediment, and water created one of the most productive landscapes on Earth.

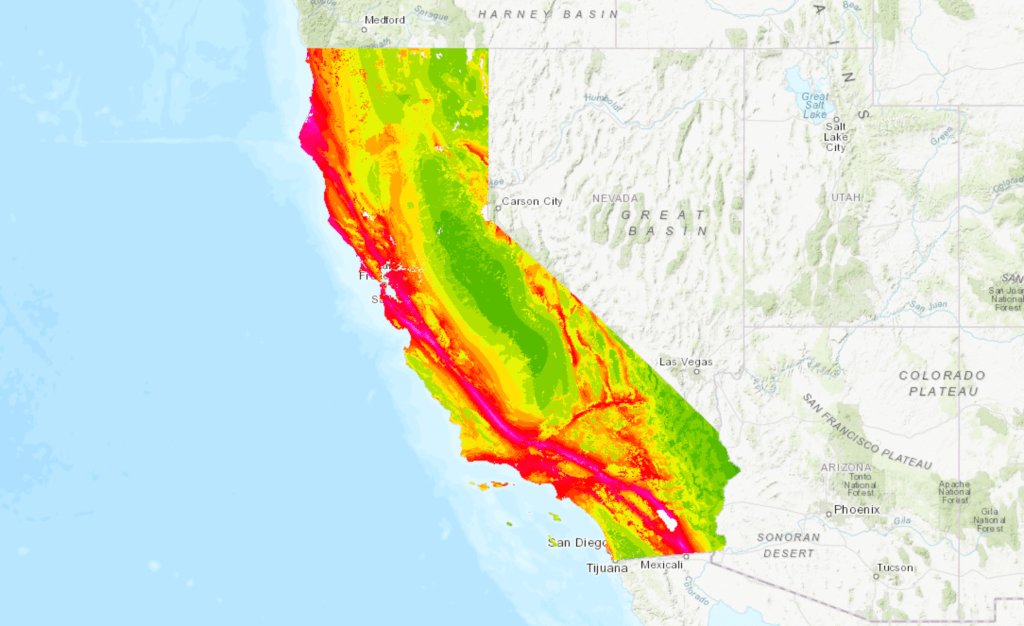

I love California’s bizarre, complicated geology. For many years, I had a wonderful raised-relief map of the state on my wall made by Hubbard Scientific (it hangs on my son’s bedroom wall today). On the map, color and molded plastic contours reveal the state’s diverse and often startling geological formations. I loved staring at it, touching it, imagining how those landscapes came to be over geologic time.

There is so much going on here geologically compared to almost any other state that geologists often describe California as one of the best natural laboratories on Earth, a place so rich and varied that entire careers have been built trying to understand how all its pieces fit together. As the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) puts it, nearly every major force that shapes the Earth’s crust is visible here, from plate collision and volcanism to basin formation and mountain uplift. Some of my favorite writers, like John McPhee, have described California as a collage of geological fragments, assembled piece by piece over deep time, in a way that more closely resembles an entire continent than a single region.

But when we think about California’s geology, most of us probably imagine the Sierra Nevada’s towering granite peaks, the pent-up force of the San Andreas Fault, or the fact that Lassen Peak is still an active volcano. Those places grab our attention. Yet when it comes to a geological feature that has quietly shaped daily life in California more than almost any other, we should consider the Central Valley, arguably the state’s most important geological masterpiece.

Sure, the valley is flat as a tabletop, stretching out for mile after mile as you drive Interstate 5 or Highway 99 (one of my favorites), but once you consider how it formed and what lies beneath the surface, the Central Valley reveals itself as a truly remarkable place on the planet, another superlative in our state, which, of course, is already full of them.

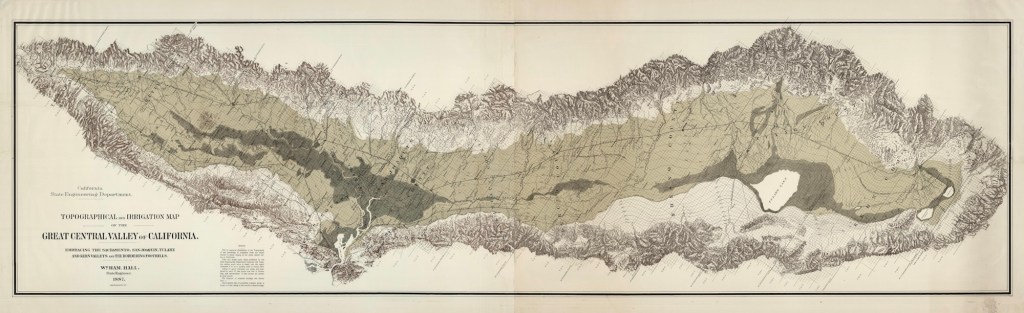

The Central Valley was formed when tectonic forces lowered a broad swath of California’s crust between the rising Sierra Nevada to the east and the Coast Ranges to the west, creating a long, subsiding basin that slowly filled with sediment eroded from those mountains over millions of years. For thousands of years, the southern end of the valley was dominated by Lake Tulare, a mega-freshwater lake that was once the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi. You might remember that just a few years ago, Lake Tulare briefly reappeared after a series of powerful atmospheric river storms. I went up there and flew my drone because I was working on a story about the construction of California’s long-troubled high-speed rail, which had halted construction because of the new old lake.

On the other side in the west, the Coast Ranges rise up, hemming in the valley and basically holding it in place, forming something like a gigantic, hundreds-of-miles-long bathtub. One popular Instagrammer commented that it looks as if someone used a huge ice cream scoop to dig out the valley. As the surrounding mountains continued to rise, rain, snowmelt, and wind carried untold tons of silt and sediment downslope, steadily depositing them into this enormous basin over millions of years.

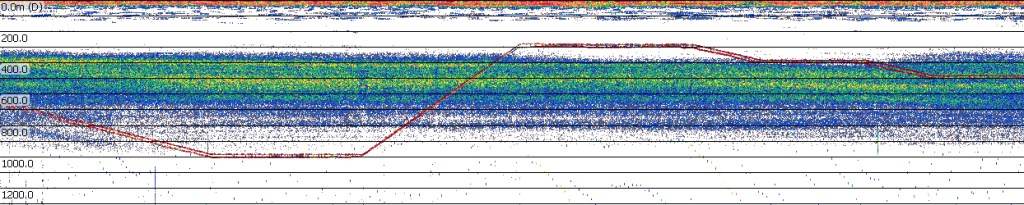

This process created what geologists call the Great Valley Sequence, a staggering accumulation of sedimentary material that, in some western portions of the basin, reaches a depth of 20,000 meters, or approximately 66,000 feet. Ten MILES.

This long, slow process produced what geologists call the Great Valley Sequence, an immense stack of sedimentary rock built up over tens of millions of years as the basin steadily subsided and filled. In some western portions of the valley, that accumulated package reaches a depth of 20,000 meters in thickness, about 66,000 feet, or close to ten miles of layered geological history lying beneath the surface. That’s kind of mind-blowing.

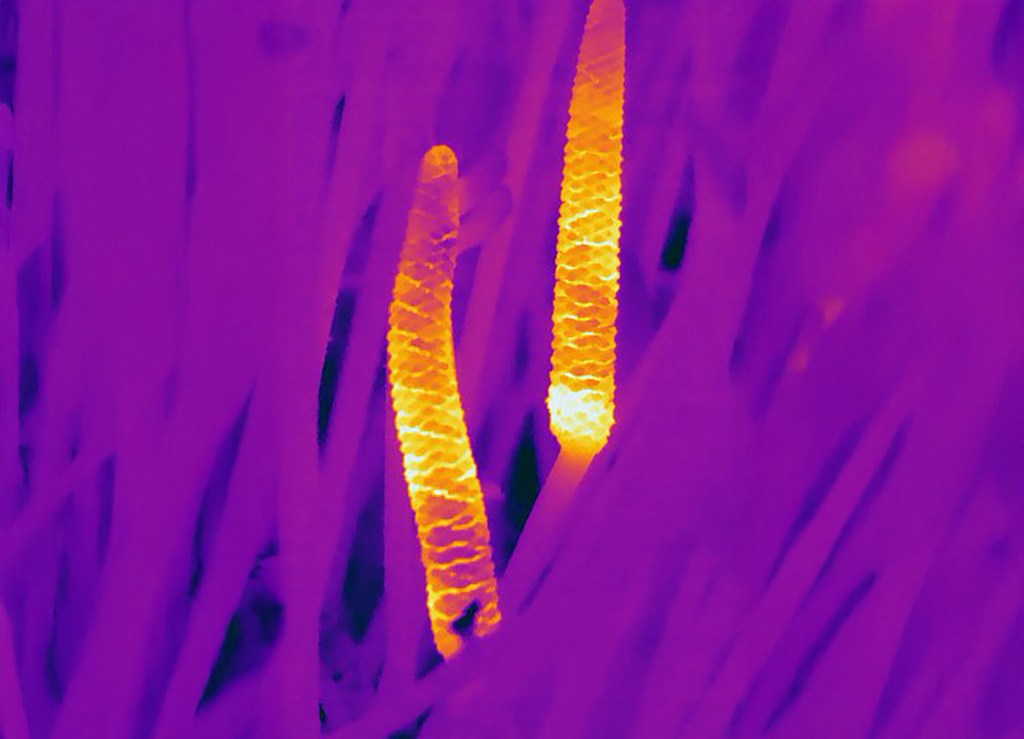

It’s not just “dirt”; it’s a ridiculously deep, nutrient-rich record of California’s geologic history. There are the remains of trillions of diatoms, or microscopic plankton, whose organic remains were crushed into oil shales that are home to significant petroleum deposits. During the late Pleistocene and into the Holocene, the southern end of the valley was dominated by Lake Tulare, mentioned above, a vast freshwater lake that in wet periods spread across 600 to 800 square miles, making it the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi. As the water evaporated and drained, the valley floor became exceptionally flat, similar to what we see today.

Most valleys are narrow corridors carved by a single river, but the Central Valley is a vast, enclosed catchment shaped by many rivers, trapping minerals and sediments from surrounding mountains rather than letting them wash quickly out to sea. This mix created near-ideal conditions for agriculture. For the uninitiated, the Central Valley is typically divided into two major sections: the northern third, known as the Sacramento Valley, and the southern two-thirds, known as the San Joaquin Valley. That lower region can be further broken down into the San Joaquin Basin to the north and the Tulare Basin to the south.

Today, because of all that fertility, the Central Valley is one of the world’s most productive agricultural regions, growing over 230 different crops. It produces roughly a quarter of the nation’s food by value, supplies about 40 percent of U.S. fruits, nuts, and vegetables, and dominates global markets for crops like almonds, pistachios, strawberries, tomatoes, and table grapes. Truly a global breadbasket.

Of course, none of this would have been possible without water. The real turning point in California’s story was learning how to capture it, move it, and store it. From mountain snowpack to canals and reservoirs, controlling water has been the quiet engine behind much of the state’s success. When human engineering intervened in the 20th century through the Central Valley Project and the State Water Project, it essentially redirected a geological process that was already in place, replacing seasonal floods and ancient lakes with a controlled system of dams and canals.

Alas, this productivity is not without geological limits, and we’ve done a pretty good job over-exploiting the valley’s resources, particularly groundwater, to achieve these things. The same porous sediments that store our life-giving groundwater are susceptible to compaction. In parts of the San Joaquin Valley, excessive pumping has caused the land to subside, sinking by as much as 28 feet in some locations, causing the soil to crack and the landscape to physically lower as the water is withdrawn. How we deal with that is a whole other story. Recent storms have helped California’s water supply tremendously, but the state seems destined to remain in a permanently precarious state of drought.

But when you talk geology, you talk deep time. You talk about eons and erosion, mountain ranges that rise and are slowly worn down, sometimes leaving behind something as breathtaking as the granite domes of Yosemite.Against that scale, the Central Valley can seem almost plain, but as I hope I’ve made the case here, when you look a little closer at even the most mundane things, you realize there is magnificence there, and few places on this planet are as magnificent as the state of California.