How a gathering of the world’s top genetic scientists helped create a roadmap for responsible biology.

In 1975, amidst the California coastal dunes of Asilomar near Monterey, a groundbreaking conference was held that would influence the direction of biotechnology and the course of scientific research for decades to come. This was the Asilomar Conference on Recombinant DNA, an assembly marked by both controversy and consensus. Its aim was not just to debate the scientific merits of a new and potentially groundbreaking technology but also to discuss its potential impacts on society and the environment. (Berg and others had met as Asilomar before in 1973, but that initial meeting resulted in little more than a realization there would have to be more discussion).

Among the seventy-five participants from sixteen countries were Paul Berg, a Nobel laureate, Maxine Singer, a prominent molecular biologist, and many others, each bringing their own perspective and expertise to the table. They recognized the vast potential that recombinant DNA (rDNA) technology, the process of combining DNA from different species, had to offer but were equally cognizant of the potential risks involved.

Berg was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on nucleic acids, with a focus on recombinant DNA. Berg had first-hand experience with the transformative potential and risks of the technology. His ground-breaking experiments with recombinant DNA in 1972 and subsequent calls for a moratorium on such work had spurred the idea of the conference.

Maxine Singer, another significant contributor, was known for her advocacy for scientific responsibility and ethical considerations. She played a crucial role in drafting the initial letter to the journal “Science” advocating for a voluntary halt on certain types of rDNA research until its potential risks could be better understood. In 2002, Discover magazine recognized her as one of the 50 most important women in science.

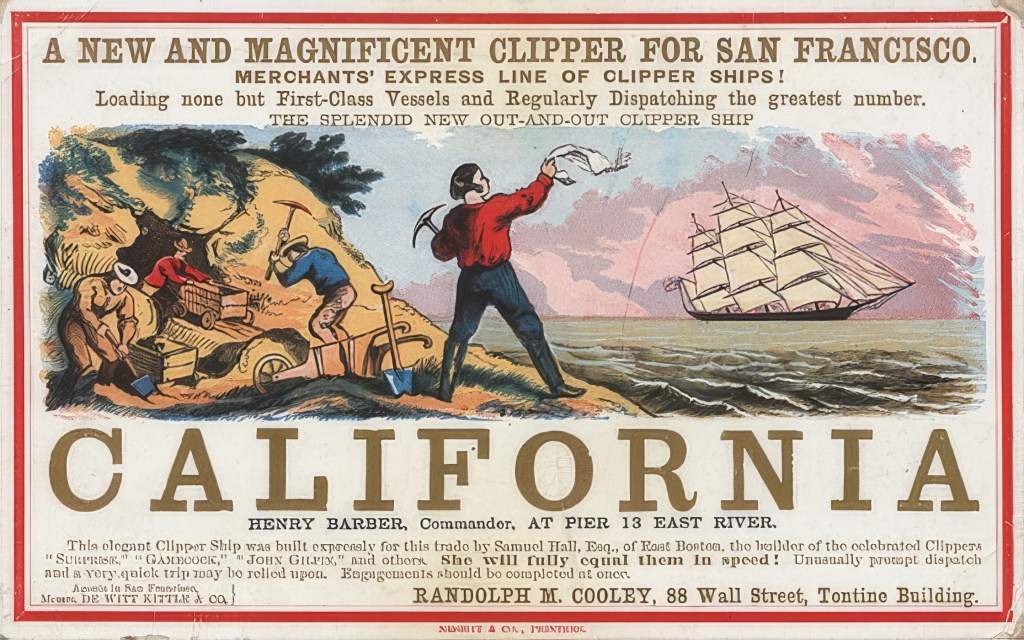

Purchase stunning art prints of iconic California scenes.

Check out our Etsy store.

The conference was the outcome of dramatic advances in molecular biology that took place mid-century. In the atomic age of the 1950s and ’60s, biology was not left behind in the wave of transformation. A pioneering blend of structural analysis, biochemical investigation, and informational decoding began to crack open the mystery of classical genetics. Central to this exploration was the realization that genes were crafted from DNA, and that this intricate molecular masterpiece held the blueprints for replication and protein synthesis.

This was a truth beautifully crystallized in the DNA model, a triumph of scientific collaboration that arose from the minds of James Watson, Francis Crick, and the often under-appreciated Rosalind Franklin. Their collective genius propelled a cascade of theoretical breakthroughs that nudged our understanding from mere observation to the brink of manipulation.

The crowning achievement of this era was the advent of recombinant DNA technology – a tool with the potential to rearrange life’s building blocks at our will. As the curtain lifted on this new stage of biological exploration, the promise and peril of our increasing control over life’s code started to unfurl.

The ability to manipulate genes marked nothing less than a seismic shift in the realm of genetics. We had deciphered a new language. Now, it was incumbent upon us to assure ourselves and all others that we possessed the requisite responsibility to utilize it.

As Siddhartha Mukherjee put it in his excellent book The Gene: An Intimate History, “There is an illuminated moment in the development of a child when she grasps the recursiveness of language: just as thoughts can be used to generate words, she realizes, words can be used to generate thoughts. Recombinant DNA had made the language of genetics recursive.”

The conference served as a forum to deliberate the safety measures that would be needed to prevent accidental release of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) into the environment, the ethical considerations of manipulating the genetic code, and the potential implications for biological warfare. It was as much about the science as it was about its potential impact on society, mirroring aspects of the Pugwash Conferences that discussed nuclear arms control during the Cold War.

Much like the Pugwash Conferences in Pugwash, Nova Scotia, Canada, brought together scientists from both sides of the Iron Curtain to discuss the implications of nuclear technology, the Asilomar Conference sought to bridge the divide between the proponents and critics of genetic engineering. Just as nuclear technology held the promise of unlimited power and the threat of unparalleled destruction, recombinant DNA offered the allure of potential solutions for numerous diseases and the specter of unforeseen consequences.

Another analogy might be the two-page letter written in August 1939 by Albert Einstein and Leo Szilard to alert President Roosevelt to the alarming possibility of a powerful war weapon in the making. A “new and important source of energy” had been discovered, Einstein wrote, through which “vast amounts of power . . . might be generated.” “This new phenomenon would also lead to the construction of bombs, and it is conceivable . . . that extremely powerful bombs of a new type may thus be constructed. A single bomb of this type, carried by boat and exploded in a port, might very well destroy the whole port.”

The Asilomar Conference reached a consensus that with proper containment measures, most rDNA experiments could be conducted safely. This resulted in a set of guidelines that differentiated experiments based on their potential biohazards and suggested appropriate containment measures. This framework, later adopted by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the United States, provided the bedrock for the safe and ethical use of rDNA technology.

The decisions made at Asilomar had far-reaching implications for both science and society. By promoting a culture of responsibility and precaution, the conference effectively prevented a public backlash against the nascent field of genetic engineering, allowing it to flourish. Moreover, it set a precedent for scientists to take an active role in the ethical and societal implications of their work.

“The most important lesson of Asilomar,” Berg said, “was to demonstrate that scientists were capable of self-governance.” Those accustomed to the “unfettered pursuit of research” would have to learn to fetter themselves.

Today, the spirit of Asilomar lives on in the field of synthetic biology and discussions around emerging technologies such as CRISPR and gene drives. It underscores the importance of scientific self-regulation, public dialogue, and transparent communication in navigating the ethical minefields that technological advancements often present.

The Asilomar Conference was a milestone in scientific history, a demonstration that scientists are not merely the creators of knowledge but also its stewards. It showed that with open dialogue, proactive self-regulation, and a deep sense of responsibility, we can both harness the promise of scientific breakthroughs and mitigate their potential risks.