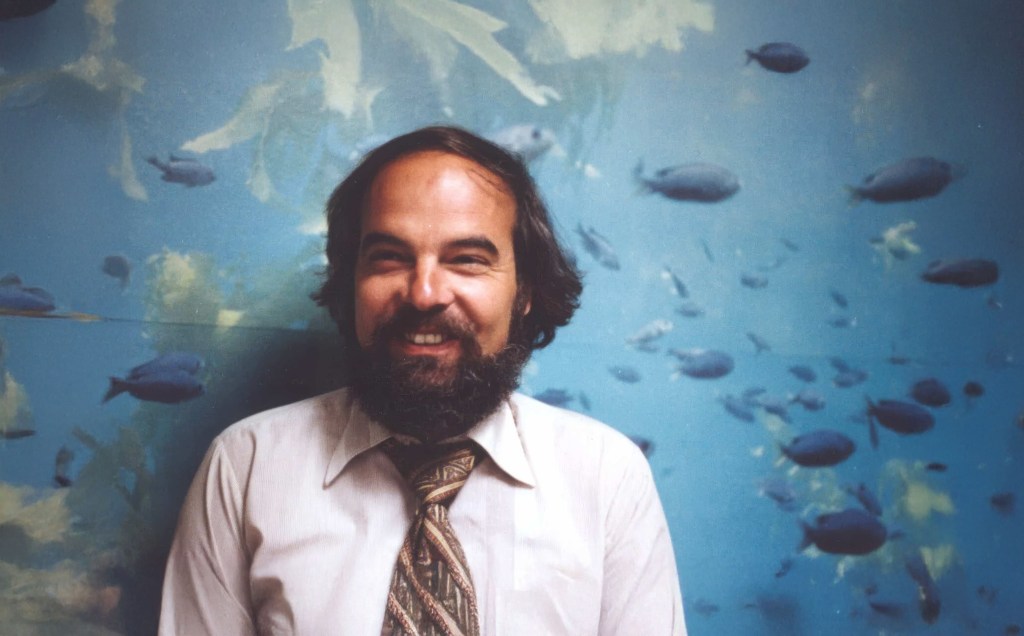

I recently took two scuba diving trips out to the Channel Islands to investigate and help remove ghost lobster traps: abandoned or lost gear that poses a serious threat to marine life. While out there, I also had a chance to explore the marine protected areas surrounding Anacapa and Santa Cruz Islands, getting a firsthand look at how these underwater reserves are helping to restore ocean health and marine life (another story on that coming). Diving in the Channel Islands is a great way for certified divers to experience the incredible biodiversity of California’s coastal waters, even if the water is cold as hell.

The Channel Islands are actually relatively close to the California mainland, just 12 miles from Ventura in the case of Anacapa. But the wild and windswept chain feels like a world apart. On a clear day, you can see them from Ventura or Santa Barbara, but oddly, few people actually visit. Compared to other national parks, they remain relatively unknown, which only adds to their quiet allure. Sometimes called the “Galápagos of North America,” these eight islands are a refuge for wildlife and a place where evolution unfolds before your eyes.

(Photo: Erik Olsen)

(Here’s a cool bit of history: there are eight Channel Islands today, but 20,000 years ago, during the last ice age when sea levels were much lower, four of them—San Miguel, Santa Rosa, Santa Cruz, and Anacapa—were connected as a single landmass called Santarosae.)

For scientists and nature lovers, the Channel Islands are more than just scenic, they’re a natural laboratory. Each island has its own shape, size, and ecological personality, shaped by millions of years of isolation. That makes them an ideal setting for the study of island biogeography, the branch of biology that looks at how species evolve and interact in isolated environments. What happens here offers insight into how life changes and adapts not just on islands, but across the planet.

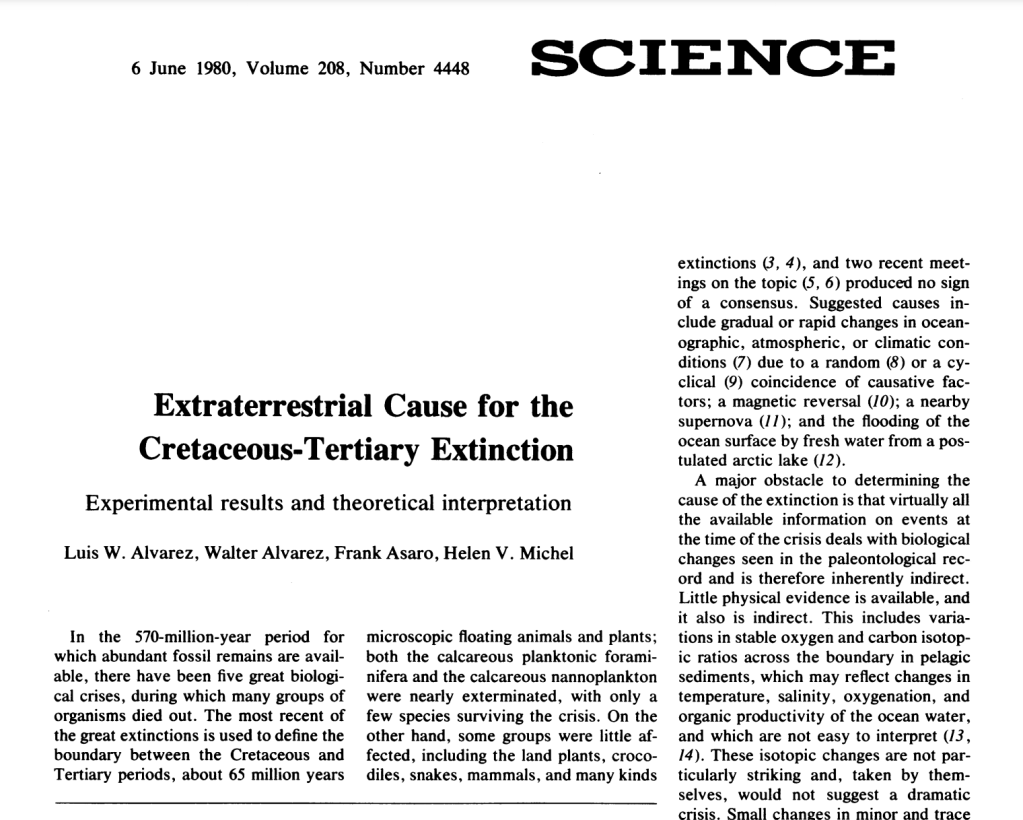

Island biogeography is anchored in the theory proposed by E.O. Wilson and Robert MacArthur in the 1960s. Their theory, focusing on the balance between immigration and extinction of species on islands, is brilliantly exemplified in the Channel Islands.

The Channel Islands’ rich mosaic of habitats, from windswept cliffs and rocky shores to chaparral-covered hillsides and dense offshore kelp forests, provides an ideal setting for studying how species adapt to varied and changing conditions. Each island functions like a separate ecological experiment, shaped by isolation, resource limits, and time. Evolution has had free rein here, tweaking species in subtle ways and, occasionally, producing striking changes.

One of the most significant studies conducted in the Channel Islands focused on the island fox (Urocyon littoralis), a species found nowhere else on Earth. Research led by the late evolutionary biologist Robert Wayne at UCLA and others showed that the fox populations on each of the six islands they inhabit have evolved in isolation, with distinct genetic lineages and physical traits. This makes them a remarkable example of rapid evolution and adaptive divergence, core processes in island biogeography.

Genetic analyses revealed that each island’s fox population carries unique genetic markers, shaped by long-term separation and adaptation to local environments. These differences aren’t just genetic, they’re physical and behavioral too. Foxes on smaller islands, for instance, tend to be smaller in body size, likely an evolutionary response to limited resources, a phenomenon known as insular dwarfism. Variations in diet, foraging behavior, and even coat coloration have been documented, offering scientists an unparalleled opportunity to study evolutionary processes in a real-world, relatively contained setting.

This phenomenon of insular dwarfism isn’t unique to the island fox. One of the most striking examples from the Channel Islands is the pygmy mammoth (Mammuthus exilis), whose fossilized remains were discovered on Santa Rosa Island. Evolving from the much larger Columbian mammoth, these ancient giants shrank to about half their original size after becoming isolated on the islands during the last Ice Age. Limited food, reduced predation, and restricted space drove their dramatic transformation, a powerful illustration of how isolation and environmental pressures can reshape even the largest of species.

Furthermore, the Channel Islands have been instrumental in studying plant species’ colonization and adaptation. Due to their isolation, the islands host a variety of endemic plant species. Research by Kaius Helenurm, including genetic studies on species such as the Santa Cruz Island buckwheat (Eriogonum arborescens) and island mallow (Malva assurgentiflora), has shown how these plants have adapted to the islands’ unique environmental pressures and limited gene flow.

The islands have been a scientific boon to researchers over the decades because they are not only home to many diverse and endemic species, but their proximity to the urban centers and the universities of California make them amazingly accessible. It’s been suggested that if Darwin had landed on the Channel Islands, he arguably could have come up with the theory of natural selection off of California, rather than happening upon the Galapagos. A 2019 book about the islands, titled North America’s Galapagos: The Historic Channel Islands Biological Survey recounts the story of a group of researchers, naturalists, adventurers, cooks, and scientifically curious teenagers who came together on the islands in the late 1930s to embark upon a series of ambitious scientific expeditions never before attempted.

The Channel Islands are renowned for their high levels of endemism — species that are found nowhere else in the world. This is a hallmark of island biogeography, as isolated landmasses often lead to the development of unique species. Darwin’s On the Origin of Species was one of the first extensive efforts to describe this phenomenon. For example, as mentioned above, the Channel Islands are home to the island fox (Urocyon littoralis), a small carnivore found only here. Each island has its own subspecies of the fox, differing slightly in size and genetics, a striking example of adaptive radiation, where a single species gives rise to multiple different forms in response to isolation and environmental pressures. That said, the foxes are also incredibly cute, but can be rather annoying if you are camping on the islands because they will ransack your food stores if you do not keep them tightly closed.

Bird life on the Channel Islands also reveals remarkable diversity and endemism. Much like the finches of the Galápagos, these islands are home to distinct avian species shaped by isolation and adaptation. The Santa Cruz Island Scrub Jay, for instance, is noticeably larger and more vividly colored than its mainland relatives, a reflection of its unique island habitat. Also, jays in pine forests tend to have longer, shallower bills, while those in oak woodlands have shorter, deeper bills. Evolutionary adaptations right out of the Darwinian playbook. Likewise, the San Clemente House Finch has evolved traits suited to its specific environment, illustrating how even common species can diverge dramatically when given time and separation.

The impacts of invasive species on island ecosystems, another critical aspect of island biogeography, are also evident in the Channel Islands. The islands have been an superb laboratory for the practice of conservation and human-driven species recovery. For example, efforts to remove invasive species, like pigs and rats, and the subsequent recovery of native species, like the island fox, provide real-time insights into ecological restoration and the resilience of island ecosystems.

These efforts at conservation and species recovery extend beyond the island fox. In 1997, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service identified that 13 plant species native to the northern Channel Islands in California were in dire need of protection under the Endangered Species Act. This need arose due to several decades of habitat degradation, primarily attributed to extensive sheep grazing. These conservation efforts have yielded good news. For instance, the island bedstraw (Galium buxifolium) expanded from 19 known sites with approximately 500–600 individuals in 1997 to 42 sites with over 15,700 individuals. Similarly, the Santa Cruz Island dudleya (Dudleya nesiotica) population stabilized at around 120,000 plants. As a result of these recoveries, both species were removed from the federal endangered species list in 2023, coinciding with the 50th anniversary of the Endangered Species Act.

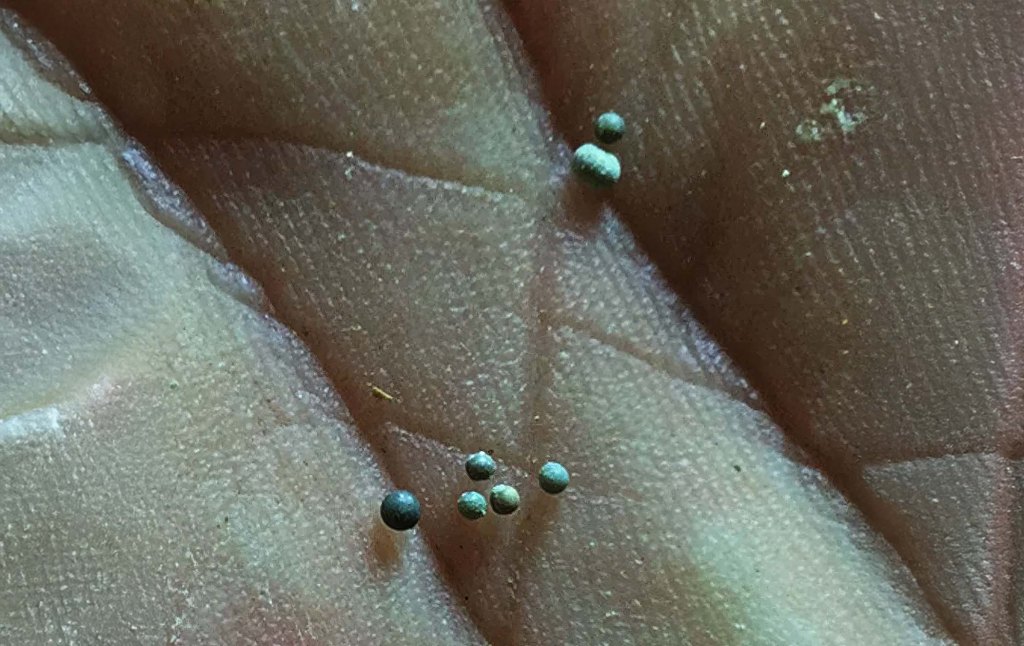

Conservation efforts at the Channel Islands extend beneath the waves, where marine protected areas (MPAs) have played a crucial role in restoring the rich biodiversity of the underwater world. I’ve seen the rich abundance of sea life firsthand on several dives at the Channel Islands, where the biodiversity feels noticeably greater than at many mainland dive sites in Southern California.

The Channel Islands Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), established in 2003, were among the first of their kind in California. The MPAs around Anacapa, Santa Cruz, and other islands act as refuges where fishing and other extractive activities are limited or prohibited, allowing marine ecosystems to recover and thrive. Over the past two decades, scientists have documented increases in the size and abundance of key species such as kelp bass, lobsters, and sheephead, alongside the resurgence of lush kelp forests that anchor a vibrant web of marine life. These protections have not only benefited wildlife but have also created living laboratories for researchers to study ecological resilience, predator-prey dynamics, and the long-term impacts of marine conservation, all taking place in the context of island biogeography.

What makes all of this possible is the remarkable decision to keep these islands protected and undeveloped. Unlike much of the California coast, the Channel Islands were set aside, managed by the National Park Service and NOAA as both a national park and a marine sanctuary. These protections have preserved not just the landscapes, but the evolutionary stories still unfolding in real time. It’s a rare and precious thing to have a living laboratory of biodiversity right in our backyard, and a powerful reminder of why preserving wild places matters.