(The Caltech Archives)

“Here in Pasadena, it is like Paradise. Always sunshine and clear air, gardens with palms and pepper trees and friendly people who smile at one and ask for autographs.” – Albert Einstein (U.S. Travel Diary, 1930-31, p. 28)

Albert Einstein is often associated with Princeton, where he spent his later years as a towering intellectual figure, and with Switzerland, where he worked as a young patent clerk in Bern. It was in that spartan, dimly lit office, far from the great universities of the time, that Einstein quietly transformed the world. In 1905, his annus mirabilis or “miracle year,” he published a series of four groundbreaking papers that upended physics and reshaped humanity’s understanding of space, time, and matter. With his insights into the photoelectric effect, Brownian motion, special relativity, and the equivalence of mass and energy (remember E=mc2?), he not only laid the foundation for quantum mechanics and modern physics but also set in motion technological revolutions that continue to shape the future. Pretty good for a guy who was just 26.

Albert Einstein spent his later years as a world-famous scientist traveling the globe and drawing crowds wherever he went. His letters and travel diaries show how much he loved exploring new places, whether it was the mountains of Switzerland, the temples of Japan, or the intellectual circles of his native Germany. In 1922, while on his way to accept the Nobel Prize, he and his wife, Elsa, arrived in Japan for a six-week tour, visiting Tokyo, Kyoto, and Osaka.

But of all the places he visited, one city stood out for him in particular. Pasadena, with its warm weather, lively culture, and, most importantly, its reputation as a scientific hub, had a deep personal appeal to Einstein. He visited Pasadena during the winters of 1931, 1932, and 1933, each time staying for approximately two to three months. These stays were longer than many of his other travels, giving him time to fully immerse himself in the city. He spent time at Caltech, exchanging ideas with some of the brightest minds in physics, and fully embraced the California experience, rubbing elbows with Hollywood stars (Charlie Chapman among them), watching the Rose Parade, and even tutoring local kids. Einstein may have only been a visitor, but his time in Pasadena underscores how deeply rooted science was in the city then, and how strongly that legacy endures today. Pasadena remains one of the rare places in the country where scientific inquiry and creative spirit continue to thrive side by side. Pasadena was among the earliest cities to get an Apple Store, with its Old Pasadena location opening in 2003.

Few scientists have received the public adulation that Einstein did during his winter stays in Pasadena. As a hobbyist violinist, he engaged in one-on-one performances with the conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Local artists not only painted his image and cast him in bronze but also transformed him into a puppet figure. Frank J. Callier, a renowned violin craftsman, etched Einstein’s name into a specially carved bow and case.

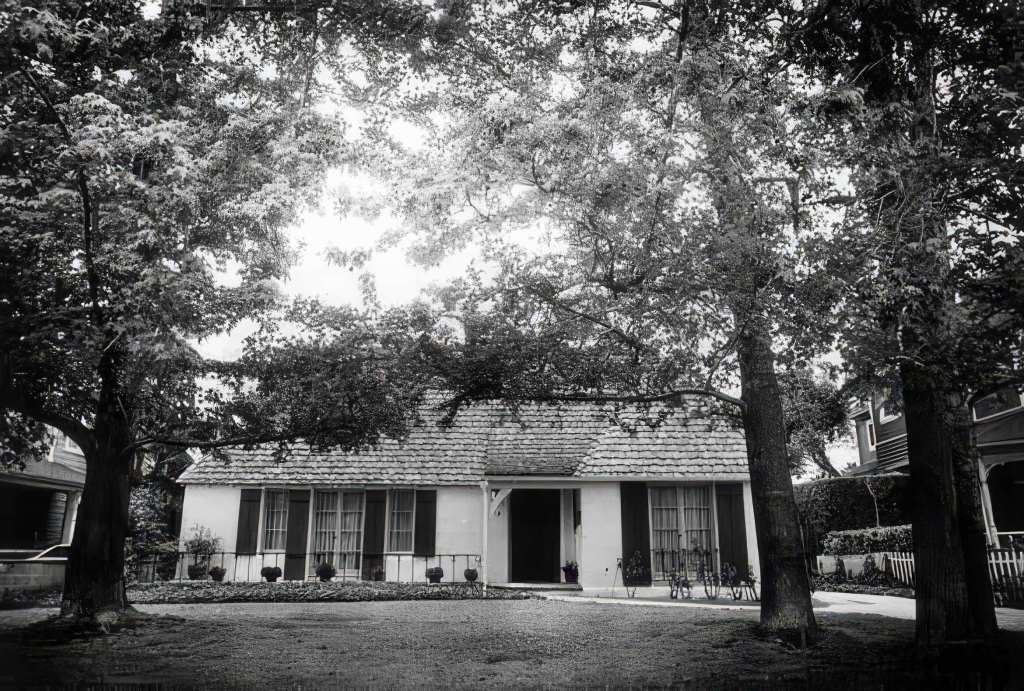

During his first winter of residence in 1931, Einstein lived in a bungalow at 707 South Oakland Avenue. During the following two winters, he resided at Caltech’s faculty club, the Athenaeum, a faculty and private social club that is still there today.

Yet, the FBI was keeping a watchful eye on Einstein as well. He was one of just four German intellectuals, including Wilhelm Foerster, Georg Nicolai, and Otto Buek, to sign a pacifist manifesto opposing Germany’s entry into World War I. Later, Einstein aligned himself with Labor Zionism, a movement that supported Jewish cultural and educational development in Palestine, but he opposed the formation of a conventional Jewish state, instead calling for a peaceful, binational arrangement between Jews and Arabs.

(Courtesy of the Caltech Archives.)

After his annus mirabilis in 1905, Einstein’s influence grew rapidly. In 1919, his theory of relativity was confirmed during a solar eclipse by the English astronomer Sir Arthur Eddington. The announcement to the Royal Society made Einstein an overnight sensation among the general public, and in 1922, he was awarded the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics. While teaching at the University of Berlin in 1930, Arthur H. Fleming, a lumber magnate and president of Caltech’s board, successfully persuaded him to visit the university during the winter. The visit was intended to remain a secret, but Einstein’s own travel arrangements inadvertently made it public knowledge.

(Courtesy of the Caltech Archives)

After arriving in San Diego on New Year’s Eve 1930, following a month-long journey on the passenger ship Belgenland, Einstein was swarmed by reporters and photographers. He and his second wife, Elsa, were greeted with cheers and Christmas carols. Fleming then drove them to Pasadena, where they settled into the bungalow on S Oakland Ave.

During their first California stay, the Einsteins attended Charlie Chaplin’s film premiere and were guests at his Beverly Hills home. “Here in Pasadena, it is like Paradise,” Einstein wrote in a letter. He also visited the Mt. Wilson Observatory high in the San Gabriel Mountains. Einstein’s intellectual curiosity extended far beyond his scientific endeavors, leading him to explore the Huntington Library in San Marino, delighting in its rich collections. At the Montecito home of fellow scientist Ludwig Kast, he found comfort in being treated more as a tourist than a celebrity, relishing a brief respite from the spotlight.

In Palm Springs, Einstein relaxed at the winter estate of renowned New York attorney and human rights advocate Samuel Untermeyer. He also embarked on a unique adventure to the date ranch of King Gillette, the razor blade tycoon, where he left with a crate of dates and an intriguing observation. He noted that female date trees thrived with nurturing care, while male trees fared better in tough condition: “I discovered that date trees, the female, or negative, flourished under coddling and care, but in adverse conditions the male, or positive trees, succeeded best,” he said in a 1933 interview.

Purchase stunning coffee mugs and art prints of California icons.

Check out our Etsy store.

Not exactly relativity, but a curiosity-driven insight reflecting his ceaseless fascination with the world.

During his three winters in Pasadena, Einstein’s presence was a source of intrigue and inspiration. Students at Caltech were treated to the sight of the disheveled-haired genius pedaling around campus on a bicycle, launching paper airplanes from balconies, and even engaging in a heated debate with the stern Caltech president and Nobel laureate, Robert A. Millikan, on the steps of Throop Hall. Precisely what they debated remains a mystery. (Maybe something about the dates?)

During his final winter in California, a near-accident led the couple to move into Caltech’s Athenaeum. His suite, No. 20, was marked with a distinctive mahogany door, a personal touch from his sponsor, Fleming. In 1933, as Nazi power intensified in Germany, Einstein began searching for a safe place to continue his work. Although Caltech made an offer, it was Princeton University‘s proposal that ultimately won him over. Einstein relocated to Princeton that same year, where he played a significant role in the development of the Institute for Advanced Study and remained there until his death in 1955.

Today, a large collection of Einstein’s papers are part of the Einstein Papers Project at Caltech. And Einstein’s suite at Caltech’s Athenaeum, still displaying the mahogany door, serves as a physical reminder of his visits.

During his third and final visit to Caltech in 1933, Hitler rose to power as Chancellor of Germany. Realizing that, as a Jew, he could not safely return home, Einstein lingered in Pasadena a little longer before traveling on to Belgium and eventually Princeton, where he received tenure. He never returned to Germany, or to Pasadena. Yet he often spoke fondly of the California sunshine, which he missed, and in its own way, the sunshine seemed to miss him too.