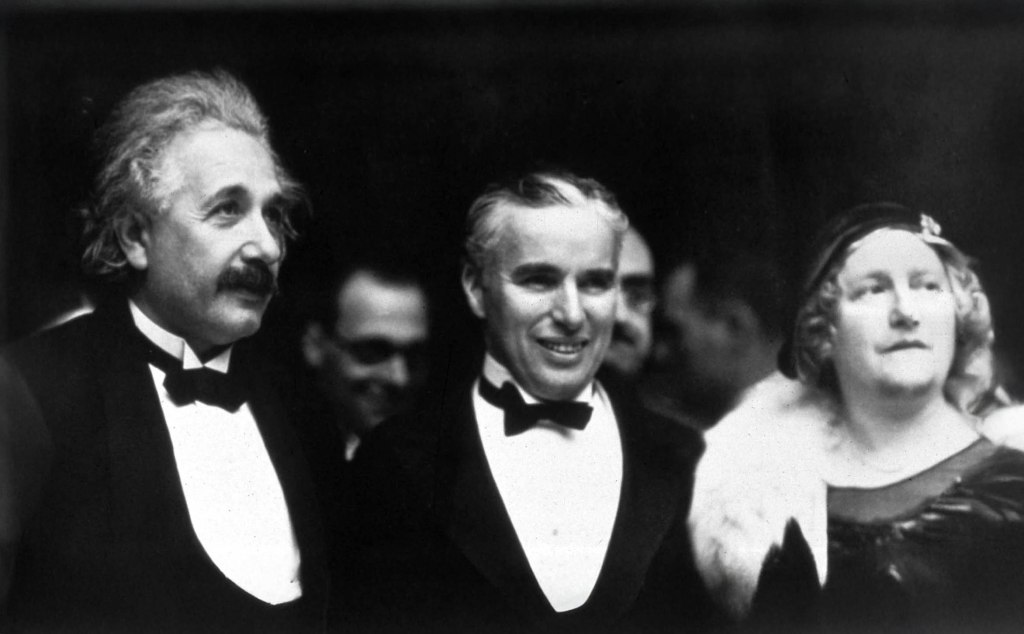

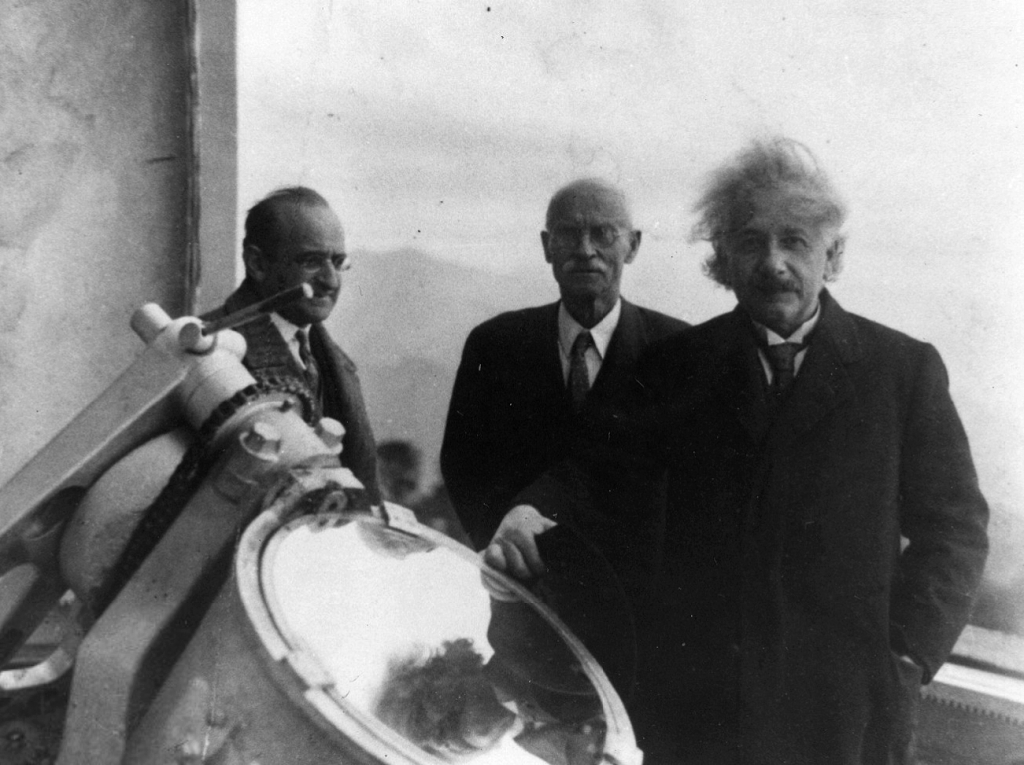

We wrote a piece a while back about the three winters Albert Einstein spent in Pasadena, a little-known chapter in the life of a man who changed how we understand the universe. It was our way of showing how Einstein, often seen as a figure of European academia and global science, formed a real affection for California and for Pasadena in particular. It’s easy to picture him walking the streets here, lost in thought or sharing a laugh with Charlie Chaplin. The idea of those two geniuses, one transforming physics and the other revolutionizing comedy, striking up a friendship is something worth imagining.

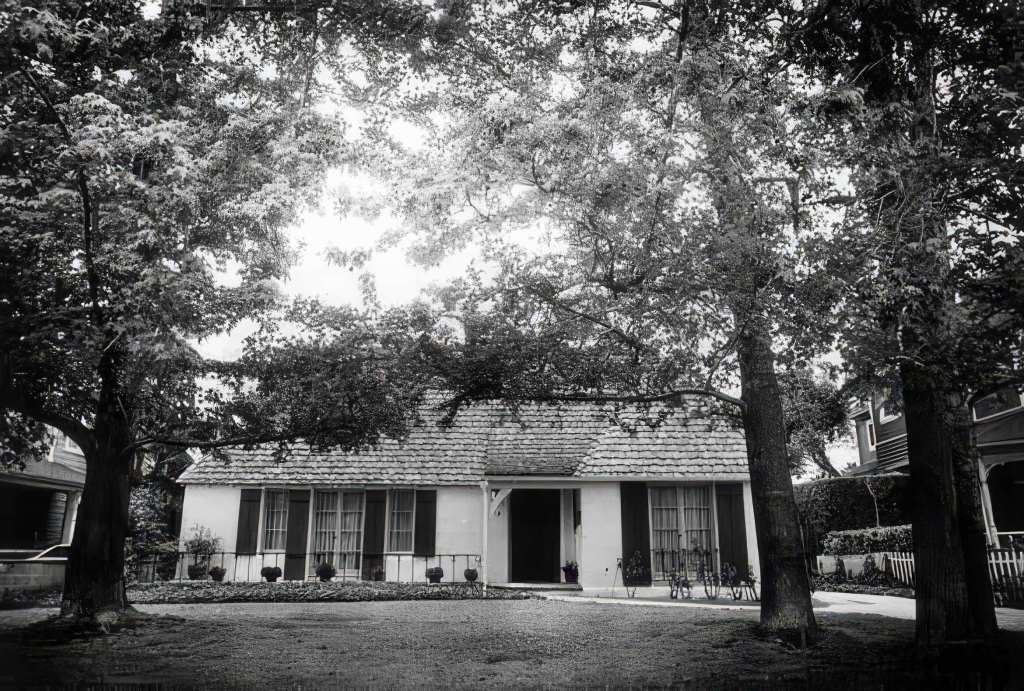

But Einstein’s connection to Pasadena didn’t end there. It lives on in a small, nondescript building near the Caltech campus, where a group of researchers continues to study and preserve the legacy he left behind.

The Einstein Papers Project (EPP) at Caltech is one of the most ambitious and influential scientific archival efforts of the modern era. It’s not just about preserving Albert Einstein’s work—it’s about opening a window into the mind of one of the most brilliant thinkers in history. Since the late 1970s, a dedicated team of scholars has been working to collect, translate, and annotate every significant document Einstein left behind. While the project is headquartered at the California Institute of Technology, it collaborates closely with Princeton University Press and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, which houses the original manuscripts.

(The Caltech Archives)

The idea began with Harvard physicist and historian Gerald Holton, who saw early on that Einstein’s vast output—scientific papers, personal letters, philosophical musings—deserved a meticulously curated collection. That vision became the Einstein Papers Project, which has since grown into a decades-long effort to publish The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, now spanning over 15 volumes (and counting). The project’s goal is as bold as Einstein himself: to assemble a comprehensive record of his life and work, from his earliest student notebooks to the letters he wrote in the final years of his life.

Rather than being stored in a traditional library, these documents are carefully edited and presented in both print and online editions. And what a treasure trove it is. You’ll find the famous 1905 “miracle year” papers that revolutionized physics, laying the foundation for both quantum mechanics (which Einstein famously derided) and special relativity. You’ll also find handwritten drafts, scribbled calculations, and long chains of correspondence—sometimes with world leaders, sometimes with lifelong friends. These documents don’t just chart the course of scientific discovery; they reveal the very human process behind it: doubt, revision, flashes of inspiration, and stubborn persistence.

Some of the most fascinating material involves Einstein’s attempts at a unified field theory, an ambitious effort to merge gravity and electromagnetism into one grand framework. He never quite got there, but his notebooks show a mind constantly working, refining, rethinking—sometimes over decades.

But the project also captures Einstein the person: the political thinker, the pacifist, the refugee, the cultural icon. His letters reflect a deep concern with justice and human rights, from anti-Semitism in Europe to segregation in the United States. He corresponded with Sigmund Freud about the roots of violence, with Mahatma Gandhi about nonviolent resistance, and with presidents and schoolchildren alike. The archive gives us access to the full spectrum of who he was, not just a scientist, but a citizen of the world.

One of the most exciting developments has been the digitization of the archive. Thanks to a collaboration with Princeton University Press, a large portion of the Collected Papers is now freely available online through the Digital Einstein Papers website. Students, teachers, historians, and science nerds around the globe can now browse through Einstein’s original documents, many of them translated and annotated by experts. The most recent release, Volume 17, spans June 1929 to November 1930, capturing Einstein’s life primarily in Berlin as he travels across Europe for scientific conferences and to accept honorary degrees. The volume ends just before his departure for the United States. Princeton has a nice story on the significance of that particular volume by EPP Editor Josh Eisenthal.

For scholars, the project is a goldmine. It’s not just about Einstein—it’s about the entire intellectual climate of the 20th century. His collaborations and rivalries, his responses to global upheaval, and his reflections on science, faith, and ethics all provide insight into a remarkable era of discovery and change. His writings also show a playful, curious side—his love of music, his wit, and his habit of thinking in visual metaphors.

Caltech’s role in all this goes beyond simple stewardship. The Einstein Papers Project is a reflection of the institute’s broader mission: to explore the frontiers of science and human understanding. For decades, Caltech has been a breeding ground for great minds. As of January 23, 2025, there are 80 Nobel laureates who have been affiliated with Caltech, making it the institution with the highest number of Nobelists per capita in America. By preserving and sharing Einstein’s legacy, Caltech helps keep alive a conversation about curiosity, responsibility, and the enduring power of ideas.