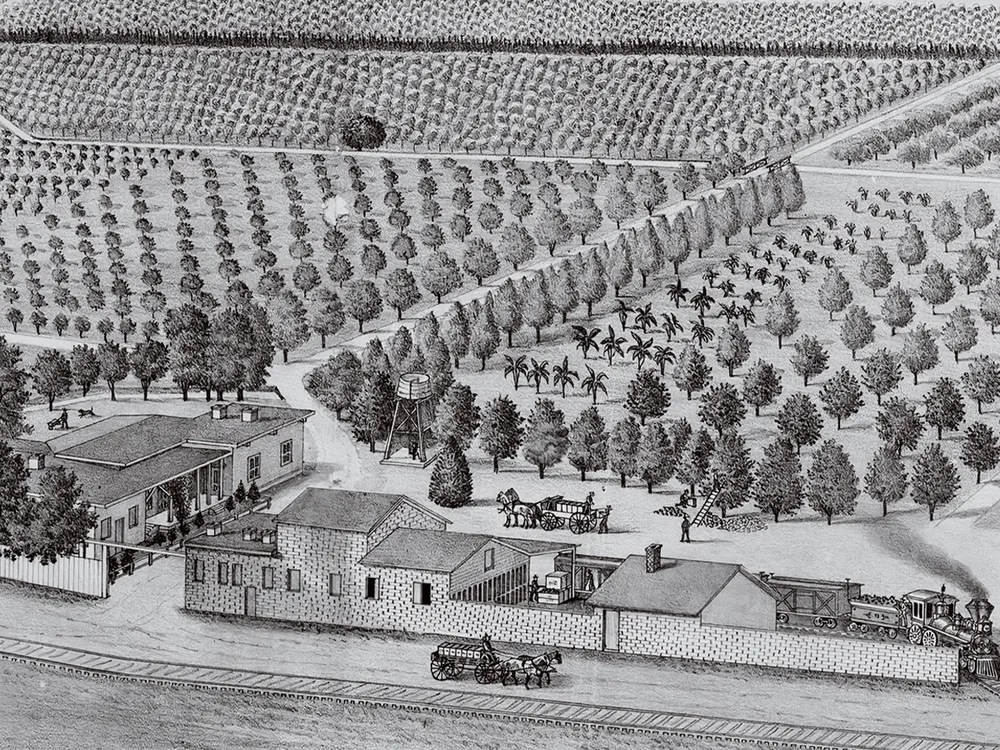

Monterey Canyon stretches nearly 95 miles out to sea, plunging over 11,800 feet into the depths—one of the largest submarine canyons on the Pacific Coast, hidden beneath the waves. (Courtesy: Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute MBARI)

Standing at Moss Landing, a quaint coastal town known for its fishing heritage, bustling harbor, and the iconic twin smokestacks of its power plant, you might never guess that a massive geological feature lies hidden beneath the waves. From this unassuming spot on the California coast, Monterey Canyon stretches into the depths, a colossal submarine landscape that rivals the grandeur of the Grand Canyon itself.

Monterey Canyon, often called the Grand Canyon of the Pacific, is one of the largest and most fascinating submarine canyons in the world. Stretching over 95 miles from the coast of Monterey, California, and plunging to depths exceeding 3,600 meters (11,800 feet), this underwater marvel rivals its terrestrial counterpart in size and grandeur. Beneath the surface of Monterey Bay, the canyon is a hotspot of geological, biological, and scientific exploration, offering a window into Earth’s dynamic processes and the mysterious ecosystems of the deep sea.

(Courtesy: Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute MBARI)

Monterey Canyon owes its impressive scale and structure to the patient yet powerful forces of geological time. Formed over millions of years, Monterey Canyon has been shaped by a range of geological processes. One prevailing theory is that the canyon began as a river channel carved by the ancestral Salinas River, which carried sediments from the ancient Sierra Nevada to the ocean. As sea levels fluctuated during ice ages, the river extended further offshore, deepening the canyon through erosion. Another hypothesis points to tectonic activity along the Pacific Plate as a significant factor, creating fault lines and uplifting areas around the canyon while subsidence allowed sediment to accumulate and flow into the deep. These forces, combined with powerful turbidity currents—underwater landslides of sediment-laden water—worked in tandem to sculpt the dramatic contours we see today. Together, one or several of these processes forged one of Earth’s most dramatic underwater landscapes.

While the geology is awe-inspiring, the biology of Monterey Canyon makes it a living laboratory for scientists. The canyon is teeming with life, from surface waters to its darkest depths. Near the top, kelp forests and sandy seafloors support a wide variety of fish, crabs, and sea otters, while the midwater region, known as the “twilight zone,” is home to bioluminescent organisms like lanternfish and vampire squid that generate light for survival. Lanternfish, for example, employ bioluminescence to attract prey and confuse predators, while vampire squid use light-producing organs to startle threats or escape unnoticed into the depths. In the canyon’s deepest reaches, strange and hardy creatures thrive in extreme conditions, including the ghostly-looking Pacific hagfish, the bizarre gulper eel, and communities of tube worms sustained by chemical energy from cold seeps.

operated vehicle (ROV) Tiburon in the outer Monterey Canyon at a depth of approximately

770 meters. (Courtesy: Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute MBARI)

The barreleye fish, captured in stunning video footage by MBARI, is one of the canyon’s most fascinating inhabitants. This deep-sea fish is known for its’ domed transparent head, which allows it to rotate its upward-facing eyes to track prey and avoid predators in the dimly lit depths. Its unique adaptations highlight the remarkable ingenuity of life in the deep ocean. Countless deep-sea creatures possess astonishing adaptations and behaviors that continue to amaze scientists and inspire awe. Only in recent decades have we gained the technology to explore the depths and begin to uncover their mysteries.

The canyon’s rich biodiversity thrives on upwelling currents that draw cold, nutrient-rich water to the surface, triggering plankton blooms that sustain a complex food web. This process is vital in California waters, where it supports an astonishing array of marine life, from deep-sea creatures to surface dwellers like humpback whales, sea lions, and albatrosses. As a result, Monterey Bay remains a crucial habitat teeming with life at all levels of the ocean.

operated vehicle (ROV) Tiburon in the outer Monterey Canyon at a depth of 1,200 meters.

(Courtesy: Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute MBARI)

What sets Monterey Canyon apart is the sheer accessibility of this underwater frontier for scientific exploration. The canyon’s proximity to the shore makes it a prime research site for organizations like the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI). Using remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and advanced oceanographic tools, MBARI scientists have conducted groundbreaking studies on the canyon’s geology, hydrology, and biology. Their research has shed light on phenomena like deep-sea carbon cycling, the behavior of deepwater species, and the ecological impacts of climate change.

This animation, the most detailed ever created of Monterey Canyon, combines ship-based multibeam data at a resolution of 25 meters (82 feet) with high-precision autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) mapping data at just one meter (three feet), revealing the canyon’s intricate underwater topography like never before.

MBARI’s founder, the late David Packard, envisioned the institute as a hub for pushing the boundaries of marine science and engineering, and it has lived up to this mission. Researchers like Bruce Robison have pioneered the use of ROVs to study elusive deep-sea animals, capturing stunning footage of creatures like the vampire squid and the elusive giant siphonophore, a colonial organism that can stretch over 100 feet, making it one of the longest animals on Earth.

Among the younger generations of pioneering researchers at MBARI, Kakani Katija stands out for her groundbreaking contributions to marine science. Katija has spearheaded the development of FathomNet, an open-source image database that leverages artificial intelligence to identify and count marine animals in deep-sea video footage, revolutionizing how researchers analyze vast datasets. Her work has also explored the role of marine organism movements in ocean mixing, revealing their importance for nutrient distribution and global ocean circulation. These advancements not only deepen our understanding of the deep sea but also showcase how cutting-edge technology can transform our approach to studying life in the deep ocean.

Two leading scientists at MBARI, Steve Haddock and Kyra Schlining, have made groundbreaking discoveries in Monterey Canyon, expanding our understanding of deep-sea ecosystems. Haddock, a marine biologist specializing in bioluminescence, has revealed how deep-sea organisms like jellyfish and siphonophores use light for communication, camouflage, and predation. His research has uncovered new species and illuminated the role of bioluminescence in the deep ocean. Schlining, an expert in deep-sea video analysis, has played a key role in identifying and cataloging previously unknown marine life captured by MBARI’s remotely operated vehicles (ROVs). Her work has helped map the canyon’s biodiversity and track environmental changes over time, shedding light on the delicate balance of life in this hidden world.

vehicles. (Courtesy: Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute MBARI)

Monterey Canyon continues to inspire curiosity and collaboration. Its unique conditions make it a natural laboratory for testing cutting-edge technologies, from autonomous underwater vehicles to sensors for tracking ocean chemistry. The canyon also plays a vital role in education and conservation efforts, with institutions like the Monterey Bay Aquarium engaging visitors and raising awareness about the importance of protecting our oceans.

As we venture deeper into Monterey Canyon—an astonishing world hidden just off our coast—we find ourselves with more questions than answers. How far can life push its limits? How do geology and biology shape each other in the depths? And how are human activities altering this fragile underwater landscape? Yet with every dive and every discovery, we get a little closer to unraveling the mysteries of one of Earth’s last great frontiers: the ocean.