Today’s newsletter is a little different. Instead of one big story focused on a single topic, I put together a short list of some of my favorite California science and nature videos. I keep a long, slightly chaotic bookmark folder of things I come across online and save for later, often pulling ideas from it when I am stuck or just need a spark.

As a long-time nonfiction video producer, there are a few things I always look for when I watch a video story. First and most simply: did I learn something? It sounds obvious, but it’s also kind of rare. If a video teaches me a new idea, fact, or helps me see the world differently, I’ll often bookmark it. Then, since I shoot and edit myself, I look for production value. There are so many approaches now, from lavish documentaries with gimbals, sliders, drones, and RED cameras, to clean explainers built entirely out of motion graphics. Some people go in the opposite direction and keep things crude and minimal, and sometimes that works, too, as you’ll see in one of my recs below. Getting both the substance and the storytelling right is difficult, and only a small fraction of what I watch pulls it off.

All of this is to say that California is overflowing with incredible science and nature stories, many of which are perfectly suited to video. I have been back here for nearly a decade after working as a video producer in Berlin and NYC, and I was born and raised in California to begin with. Even so, I feel like I have barely scratched the surface and new stories emerge every day. (One documentary I am looking forward to is Out of Plain Sight, a film about the long-hidden dumping of chemical waste off the coast near Catalina Island and the slow, unsettling process of uncovering what was left behind on the seafloor, but it has not yet come to streaming.)

So today I am turning things over to a few people who, in my view, have done an excellent job telling stories of discovery, curiosity, and place in California, and doing it through video in a way that works well.

I hope they spark the same sense of wonder in you as they did for me!

The Farthest – PBS and Crossing the Line Productions

The Farthest is one of those rare science documentaries that nails both of the things I mention above almost perfectly. It tells the story of the Voyager missions, the tiny spacecraft launched in the 1970s that are still traveling through interstellar space today, carrying with them a record of who we are/were (remember the golden records?) and an example of humanity’s aspirations to understand not just nearby planets, but what lies beyond them. Much of the film unfolds at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in La Cañada Flintridge, one of those quietly extraordinary places in California where we bring to bear science and technology to hurtle past the limits of the known world. I have visited several times, and, in fact, it’s quite close to my home. The documentary is thoughtful, beautifully produced, and deeply nourishing in the best sense. It leaves you with a feeling of awe, not just at the vastness and mystery of the universe, but at the human curiosity, innovation and persistence that help us understand our place within it. I loved it and have gone back to watch parts of it a few times.

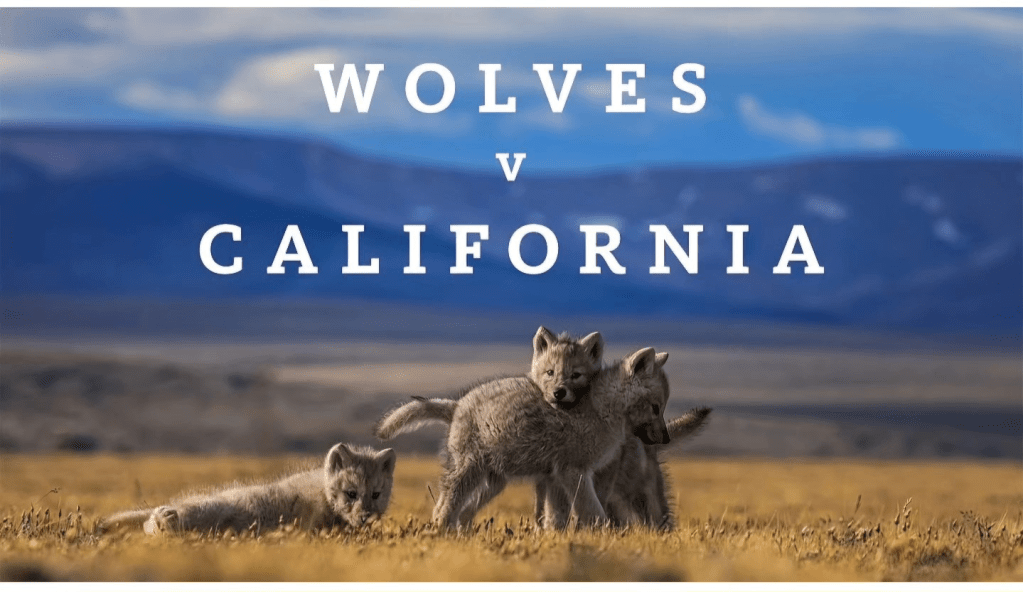

Wolves v California – Source: The California Department of Fish and Wildlife / Independent Documentary

This is a gripping look at an important conservation story that many people are probably unaware of: the return of gray wolves to California after nearly a century of absence (spoiler: we were not nice to them). The documentary is interesting because it examines the history of wolves in the region, but also the human side: the tension and the hope shared by ranchers, scientists, and environmentalists. It’s well-shot and explores how a top predator’s presence can reshape an entire ecosystem and what “coexistence” looks like in the 21st century.

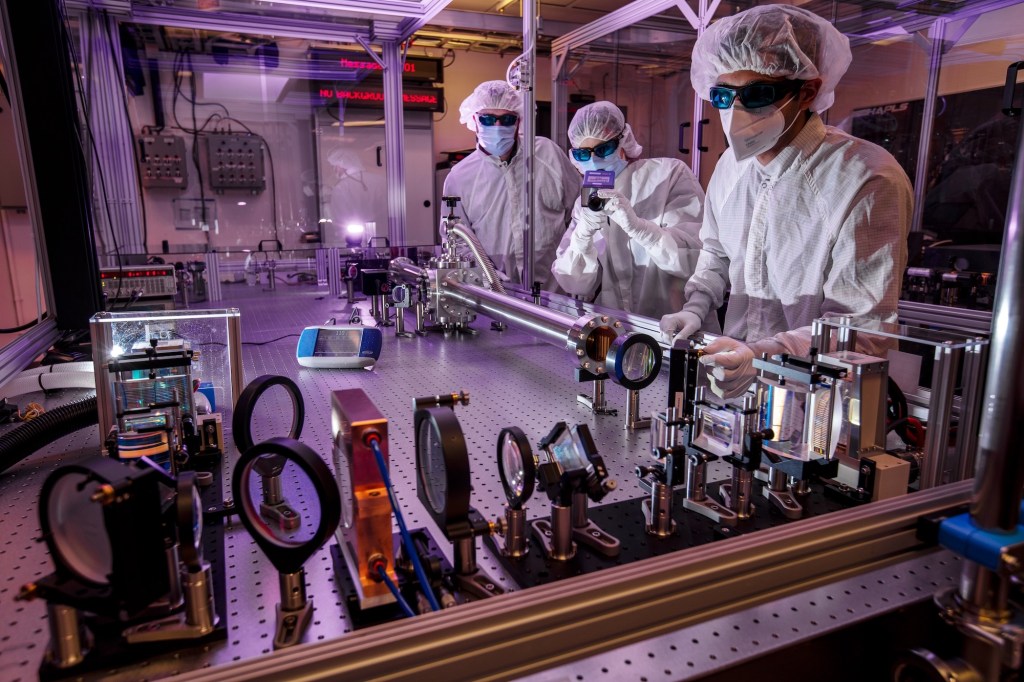

JPL and the Space Age (16 episodes) – Source: NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL)

As I mentioned above, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) is one of the most important scientific institutions in the world, and is nestled in the foothills of Los Angeles near the Arroyo Seco in La Canada Flintridge. The breadth of work that goes on there is mind-blowing, and the place uniquely deserves its own documentary series. And so, Voila!

Produced by JPL itself and the legendary Emmy Award-winning documentarian Blaine Baggett, it uses rare archival footage to document the early, high-stakes days of space exploration. There are a lot of episodes and some are better than others. You can start with the first one about the origin story of JPL, or perhaps better, watch the one on Mars. Depending on your specific interests in space exploration you will probably find cool tidbits in all of them. Spread them out, watch one while eating lunch or in your downtime. The series is fascinating because it conveys the incredible ingenuity and the “fail-fast” mentality of engineers in La Canada and Pasadena (CalTech) who have turned science fiction into reality. It’s as much a human drama as it is a strict science documentary.

This Toxic, Drying U.S. Lake Could Turn Into the ‘Saudi Arabia of Lithium’ – Source: The Wall Street Journal (WSJ)

The Wall Street Journal provides a sharp, investigative look at the Salton Sea, a place often associated with environmental disaster, that may now hold the key to the green energy revolution. (Spoiler…or maybe not: we’re going to need a LOT of lithium). The story of how the Salton Sea came to be is kind of bizarre. The doc explains how “white gold” (lithium) extracted from geothermal brine could transform the U.S. battery supply chain, making it essential viewing for anyone interested in the intersection of climate change and global business, and California is once again a key player. It is also nicely shot and produced, providing a powerful sense of the desolation and weird beauty of the place.

Lost LA: Wild L.A. – Source: KCET / PBS

“Lost LA” is an excellent series for understanding the layers of history beneath our feet, even deep history. This specific episode on “Wild L.A.” is a particularly interesting to me because it reminds us that Los Angeles was not always a sprawling concrete jungle. I’ve written a few pieces on LA’s distant past, and am always fascinated by the diverse flora and fauna that used to live here. All sorts of crazy animals. The video explores how the city was built over incredibly diverse ecosystems and how wildlife like mountain lions and hawks still cruise around this urban sprawl. The production quality is also top-notch, blending expert interviews with narrative visuals that let you see the city in a new light.

Fire Among Giants: What Happened after the Redwoods Burned? – Source: Parks California / Save the Redwoods League

After the devastating wildfires of recent years, many wondered if our ancient giants, like the redwoods and sequoia, would survive (check out our story on them). This video provides a scientific, but also emotional, look at what’s at stake. If you’ve ever visited either of these superlative trees in California, as I have (I’ve even climbed one of the largest sequoias in the world), it’s mind-blowing to think that after all the time they’ve lived, humans could be the cause of their demise (or maybe not). That said, it’s a great watch because it focuses on resilience; it shows the fascinating ways redwoods have evolved to live with fire. The footage of new green growth sprouting from blackened trunks is moving, hopeful, and provides a necessary perspective on the regenerative power of California’s most iconic forests.

EARTH FOCUS: San Clemente Island – Source: Link TV / Earth Focus

We kind of ripped this one off for a recent article and video we did, but I am posting it anyway because it’s far more comprehensive than ours. The video, part of another PBS SoCal series called Earth Focus (many of them are quite good), is a rare look at a place most people will never get to visit.

San Clemente Island is owned by the U.S. Navy, but as this documentary reveals, it’s also a laboratory for some of the most successful conservation work in the country. The video is intriguing because it shows the surprising partnership between the military and biologists to save species found nowhere else on earth. It’s a study of island biogeography, “accidental” wilderness and the high-tech methods used to track island ecology.

More Than Just Parks – Death Valley, Joshua Tree, and the Redwood – Source: The Pattiz Brothers

If you are looking for pure, cinematic escapism, this is good. These are three separate videos from a pair of filmmakers called The Pattiz Brothers. The brothers are masters of time-lapse photography and 4K cinematography. These aren’t traditional documentaries, heavy with narration; instead, they are lyrical, visual poems that capture the light, movement, and scale of California’s National Parks like Death Valley, Joshua Tree, and the Redwoods. They are perfect for relaxing and appreciating the physical beauty of our state’s diverse terrain. The soundtrack is great, too, but you could honestly just put these up on the TV in a loop and chill to them.

Listers – Source: Independent Film / Nature Culture

While not California-focused, I consider this one of the best documentaries I watched last year, and it’s got a nice section on California birds. Also, as a full-length doc, as opposed to the other shorter vids listed here, it’s free and not on some streaming service.

“Listers” takes you inside the quirky, obsessive, and high-energy world of competitive birdwatching. The guys behind it are hilarious: two stoner wannabe birders who cross the country to win the American Birding Association Big Year, chasing rare sightings, blowing their savings, and slowly realizing that the real prize isn’t the trophy but the strange subculture, friendships, and birds they fall in love with along the way. It’s a great watch because it explores the “why” behind the hobby: why people spend thousands of hours and miles to check a specific bird off a list. And unlike many of the other videos I’ve mentioned here, production values are not high. The pair shot most of the film using a comsumer-grade camcorder, but that rawness lends the film a personal, low-tech quality that actually works really well.

Ok, that’s it. I hope this gave you a few good ideas for things to watch in your spare time and a reminder of the unmatched diversity, curiosity, and sense of wonder wrapped up in California and its natural world. I am constantly adding to my bookmarks as I watch, so I may do another list like this down the road. As the saying goes, a picture is worth a thousand words, and video is just thirty of them every second. Let me know in the comments if anything here really stuck with you, or if you have your own favorite California-focused videos to recommend.