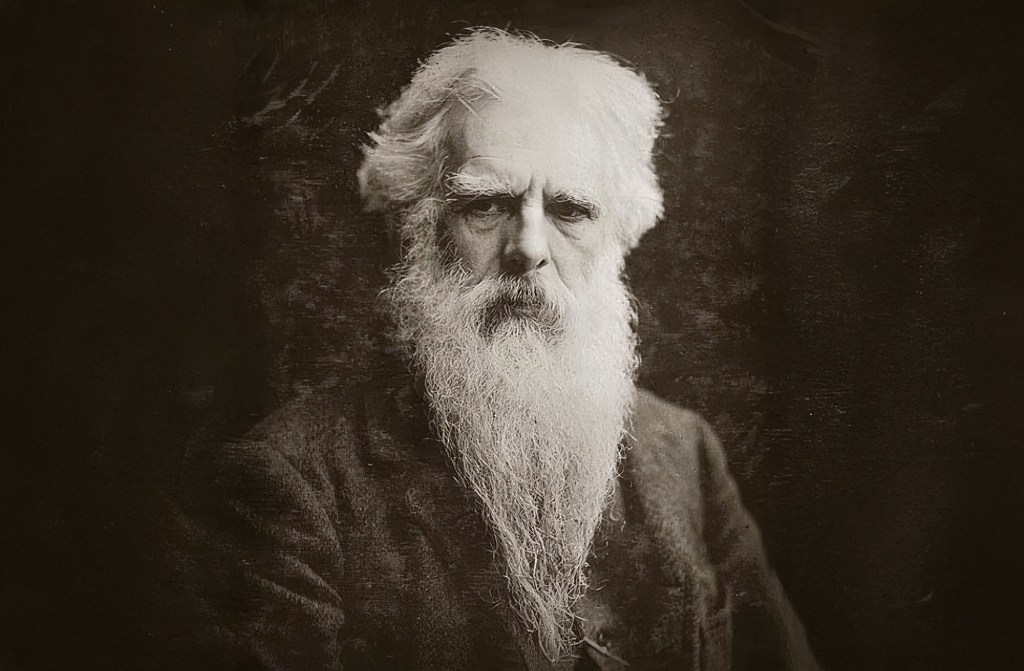

Eadweard Muybridge’s ‘Animal Locomotion’ was the first scientific study to use photography. Now, more than 130 years later, Muybridge’s work is seen as both an innovation in photography and the science of movement.

I love digging into California’s technological past. Long before Silicon Valley became the engine we think of today, the state was already a proving ground for industrial innovation. Oil, agriculture, mining, and, perhaps not surprisingly, but significantly for us here, cinema. But I’m not talking about the 1930s or 1950s, not even the 20th century. The technological roots of the movie industry in California go back much further, to a dusty track in Palo Alto.

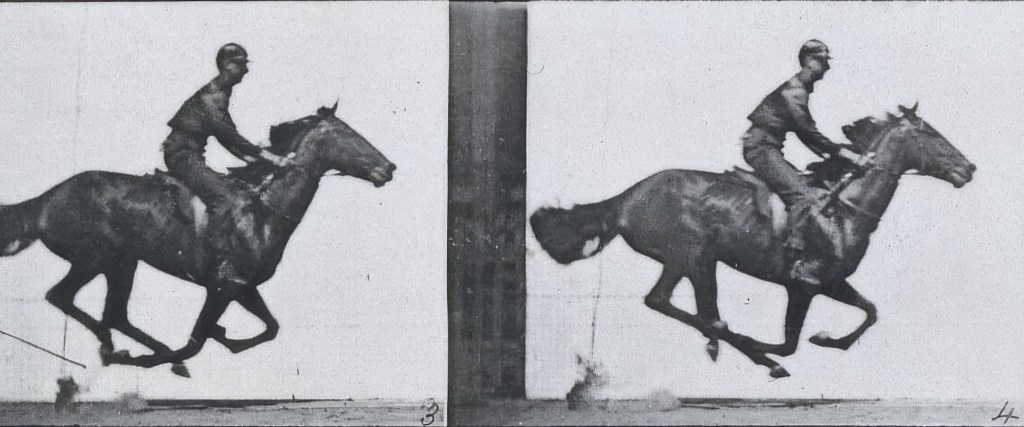

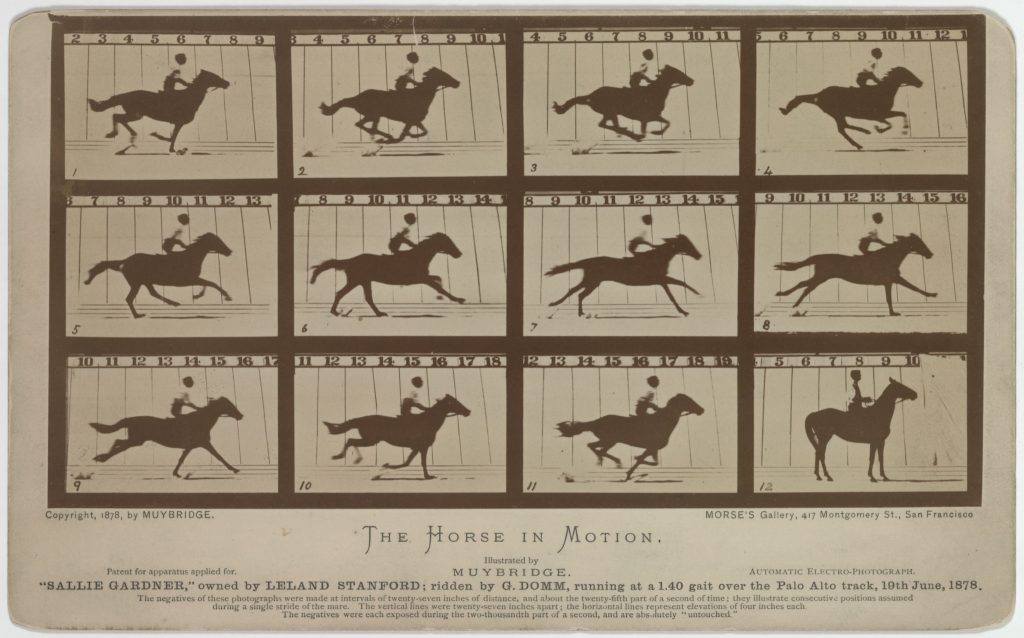

It was the summer of 1878, and a horse was caught doing something humans had argued over for centuries. For a fraction of a second, all four of its hooves left the ground at once. Not in the way painters had long imagined, legs flung forward and back in an airborne sprawl, but gathered neatly beneath the body. That brief, invisible instant, preserved by a camera, helped give birth to cinema and changed how scientists would come to understand motion in living things.

Let me explain.

The horse was a Thoroughbred mare named Sallie Gardner. The man who wanted the answer was Leland Stanford, a railroad magnate and former California governor. He would, of course, go on to lend his name to one of the great educational institutions in history. But before that, Stanford was fixated on a practical problem. As a serious horse breeder, racer, and betting guy, he wanted to know whether a galloping horse ever had all four hooves off the ground at once. It was a question with real implications for training, speed, injury, and breeding at a time when elite horse racing was big business.

Artists had painted images of horses at full gallop for centuries, and they often had the horse fully splayed out above the ground. You’ve probably seen those paintings in wealthy people’s homes or at your local country club. Or maybe not. Anyway, it turns out that the gallop is too fast, and beyond the capabilities of human. Stanford wanted the answer, and Muybridge accepted his offer to find out using pioneering new technology.

Muybridge had been into cameras for a long time. He first drew attention in 1868 for his large historical photographs of Yosemite Valley, California, well before Ansel Adams, who did not begin photographing Yosemite seriously until the 1920s.

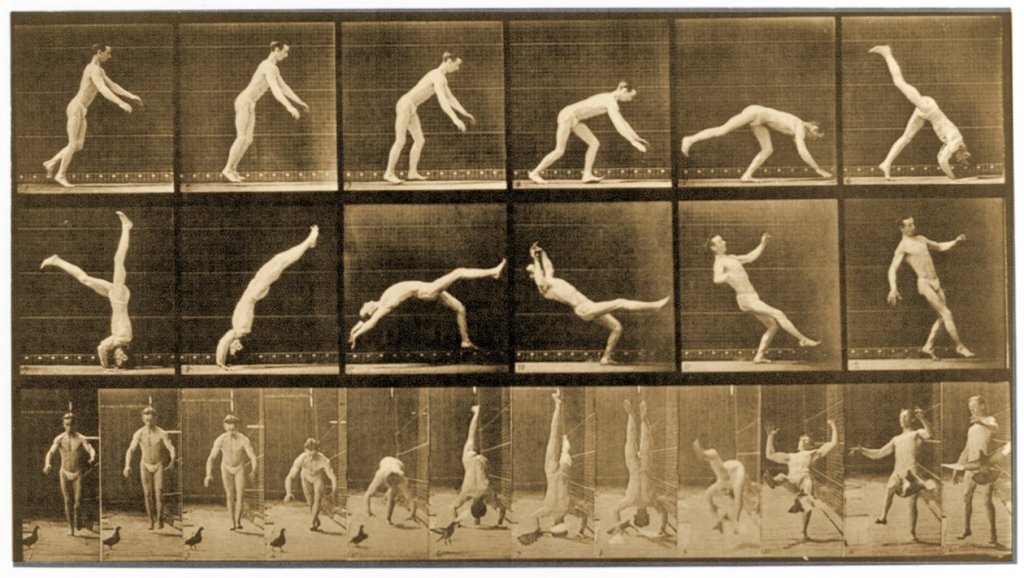

In the case of horse motion, Muybridge’s solution was not a single camera; it was more of an elaborate system. At Stanford’s Palo Alto Stock Farm, which would become Stanford University, he set up a line of cameras along a track, each one triggered by a trip wire as Sallie Gardner ran past. The result was not a blur, but a sequence of sharp, discrete instants, time broken into measurable slices. Muybridge’s images revealed something unexpected: The horse does leave the ground, but not when its legs are fully stretched. The airborne moment comes when the legs are tucked beneath the body, a moment that the human eye hadn’t seen before.

What Muybridge actually demonstrated was that motion itself could be turned into evidence. The camera was no longer just a tool for portraits or landscapes. It became a machine for understanding reality.

I guess you could say in a way that Sallie Gardner really was something like the world’s first movie star, though they didn’t call it that. The photographs did show motion on screen, per se, but they allowed you to see movement in stages. Within a year, Muybridge developed the zoopraxiscope, a projection device that animated sequences of motion using images painted or printed on rotating glass discs, often derived from his photographs.

It wasn’t a modern movie projector, and it didn’t project photographic film in the way later cinema would. But it was among the first devices to project moving images to public audiences, establishing the visual logic that cinema would later put to use. It is believed that the device was one of the primary inspirations for Thomas Edison and William Kennedy Dickson‘s Kinetoscope, the first commercial film exhibition system.

So, key to the effort was not only that Muybridge kind of overturned centuries of artistic convention, but he also, in a way, laid out the basic grammar of cinema: break time into frames, control the shutter, sequence the images, then reassemble them into motion. Hollywood would later industrialize all of this in Southern California, though the first experiment took place in Northern California.

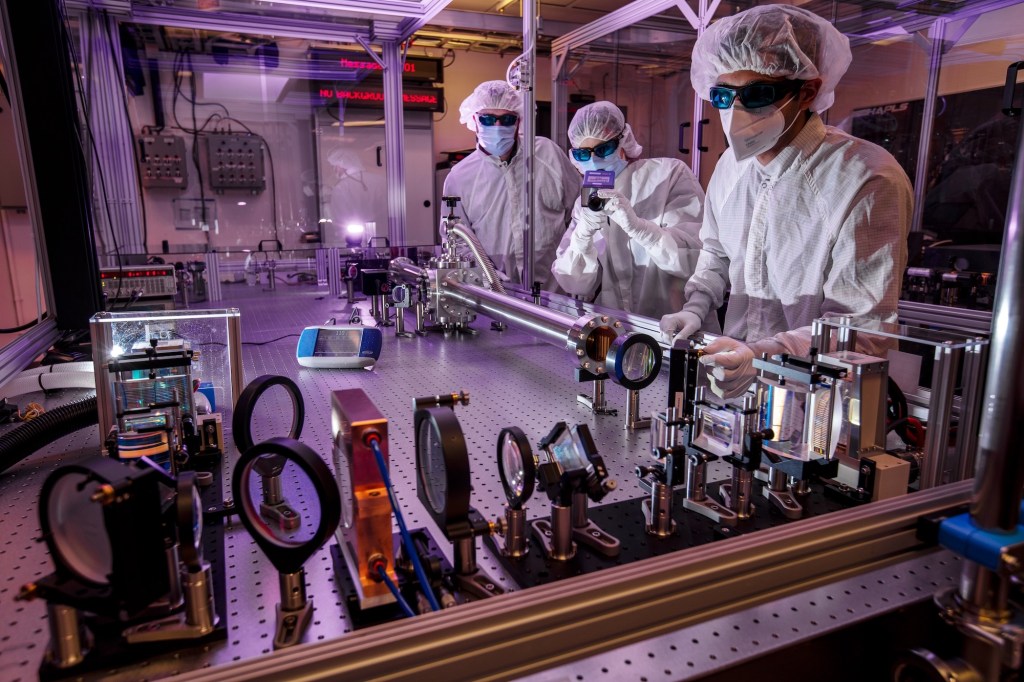

Muybridge’s technological advances mattered as much as his images (he would go on to do many other animals including humans). He pushed shutter speeds and synchronized multiple cameras. These were a few of the problems early filmmakers confronted decades later. Long before movie studios, California was already solving the physics of film.

There was also a scientific payoff. Muybridge’s sequences transformed the study of animal locomotion. For the first time, biologists and physiologists could see how bodies actually moved, not how they appeared to move. A gait could be compared with another, giving insight into biomechanics.

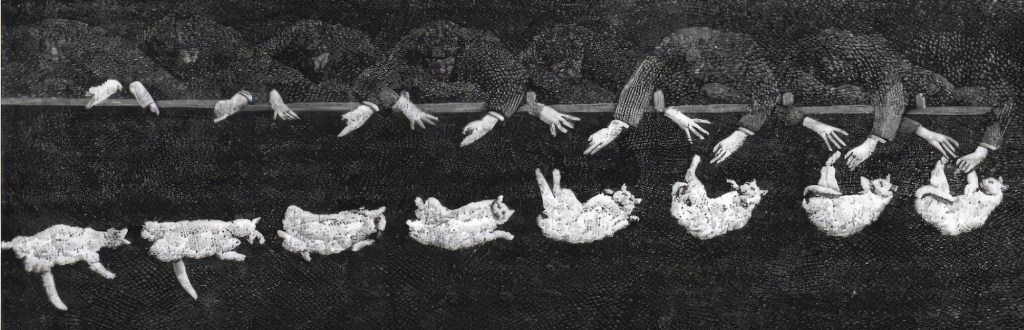

Scientists, particularly those in Europe took notice. Physiologists such as Étienne-Jules Marey built on Muybridge’s work, dropping poor cats upside down and making motion photography into a formal tool for studying living systems. It was a way for biology to see life in a new way.

Of course, today, moving imagery is essential to understanding how bodies move because motion is often too fast and complex for the naked eye. High-speed video and motion capture are used to analyze animal locomotion, study human gait and injury, improve athletic performance, and reveal behaviors in wildlife that would otherwise be invisible. Several institutions in California have been harnessing this power for years. Caltech researchers use high-speed video to fundamentally revise how scientists understand insect flight. Stanford’s Neuromuscular Biomechanics Lab identifies abnormal walking patterns in children, helping, for example, kids with cerebral palsy. At Scripps Institution of Oceanography, scientists found that fish use nearly twice as much energy hovering as they do resting, contradicting previous assumptions.

Hollywood would later perfect illusion, narrative, glamour, let alone bring digital technology to bear to give us aliens and dinosaurs, but it started in Palo Alto with a horse named Sallie Gardner, and yes, a rich guy and a curious, talented inventor. Muybridge went on to produce over 100,000 images of animals and humans in motion between 1884 and 1886.

There is a plaque that marks the site of Muybridge’s experiments. It’s California Historical Landmark No. 834, located at Stanford University on Campus Drive West, near the golf driving range. You might walk past it without knowing. But you could argue that this is one of those nondescript places where movie-making began. And of course, it happened here in California.