You can scroll endlessly through TikTok and Instagram for quick bursts of California’s beauty, but to truly sink into a subject, and to savor the craft of a great writer, you need a book. I’m an avid reader, and over the past decade I’ve dedicated a large section of my bookshelf to books about California: its wild side, its nature, and its scientific wonders.

There are surely many other books that could be included in this top ten list, but these are the finest I’ve come across in the years since returning to live in the state.They capture the extraordinary diversity of California’s landscapes and wildlife, found nowhere else on Earth, and many also explore issues and themes that hold deep importance for the state and its people. Although I’ve read some of these titles digitally, I love having many of them in print, because there are few things more satisfying than settling into a beach, a forest campsite, or a favorite chair at home with a beautifully made book in hand.

California Against the Sea: Visions for Our Vanishing Coastline by Rosanna Xia

I first discovered Rosanna Xia’s work through her stunning exposé on the thousands of DDT barrels found dumped on the seafloor near Catalina Island. It remains one of the most shocking, and yet not technically illegal, environmental scandals in California’s history.

Her recent book, California Against the Sea: Visions for Our Vanishing Coastline, is a beautifully written and deeply reported look at how California’s coastal communities are confronting the realities of climate change and rising seas. Xia travels the length of the state, from Imperial Beach to Pacifica, weaving together science, policy, and personal stories to show how erosion, flooding, and climate change are already reshaping lives. What makes the book stand out is its relative balance; it’s not a screed, nor naïvely hopeful. It nicely captures the tension between human settlement — our love and need to be near the ocean — and the coast’s natural (and unnatural, depending on how you look at it) cycles of change.

Xia is at her best when exploring adaptation and equity. She reminds us that even if emissions stopped today, the ocean will keep rising, and that not all communities have equal means to respond. The stories of engineers, Indigenous leaders, and ordinary residents highlight how resilience and adaptation must be rooted in local realities. I was especially drawn to Xia’s account of the California Coastal Commission, a wildly controversial agency that wields immense power over the future of the shoreline. Yet it was the commission and its early champions, such as Peter Douglas, who ensured that California’s coast remained open and accessible to all, a decision I consider one of the greatest legislative achievements in modern conservation history.

Thoughtful, accessible, and rooted in the coast we all care about, California Against the Sea challenges us to ask a pressing question: how can we live wisely, and with perspective, at the edge of a changing world?

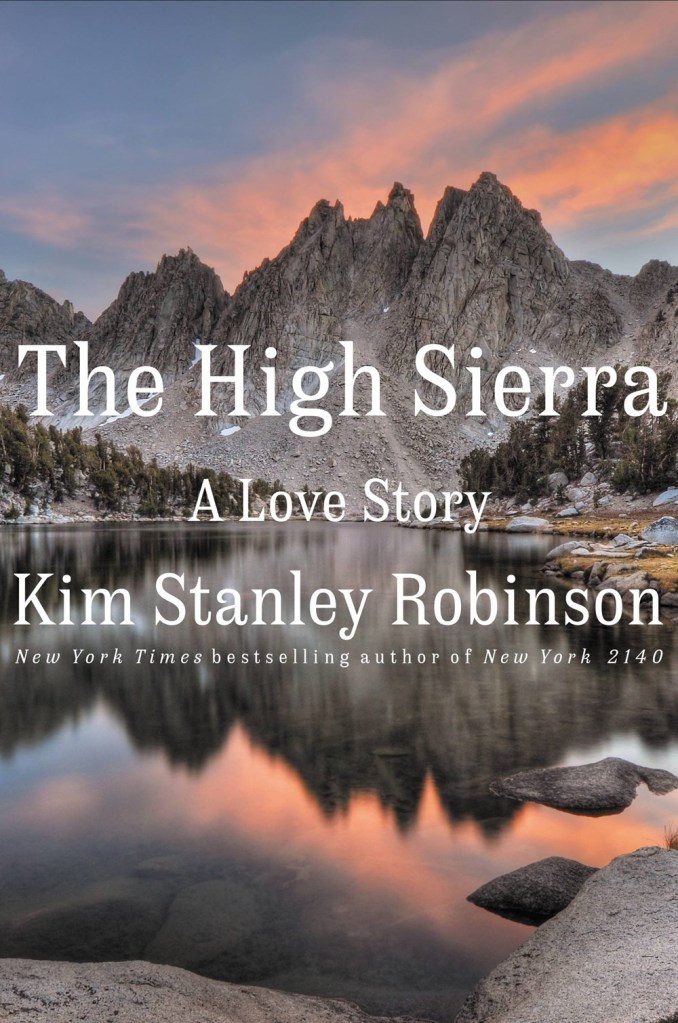

The High Sierra: A Love Story by Kim Stanley Robinson

Kim Stanley Robinson’s The High Sierra: A Love Story is an expansive, heartfelt tribute to California’s most iconic mountain range. Because of the Sierra’s vast internal basins, which are missing from many of the world’s other great mountain ranges, Robinson argues they are among the best mountains on Earth. His point is hard to refute. He makes a convincing case that the Sierra Nevada may be the greatest range in the world, formed from the planet’s largest single block of exposed granite and lifted over millions of years into its dramatic present shape.

Blending memoir, geology (my favorite part of the book), and adventure writing, Robinson chronicles his own decades of exploration in the Sierra Nevada while tracing the forces — glacial, tectonic, and emotional, that shaped both the landscape and his own life.

Considered one of our greatest living science fiction writers (I’ve read Red Mars — long, but superb — and am currently reading The Ministry for the Future — the opening chapter is gripping and terrifying), Robinson might seem an unlikely guide to the granite heights of California. Yet reading The High Sierra: A Love Story reveals how naturally his fascination with imagined worlds extends into this very real one. The drama of the range, with its light, vastness, and sculpted peaks and basins, feels like raw material for his other universes.

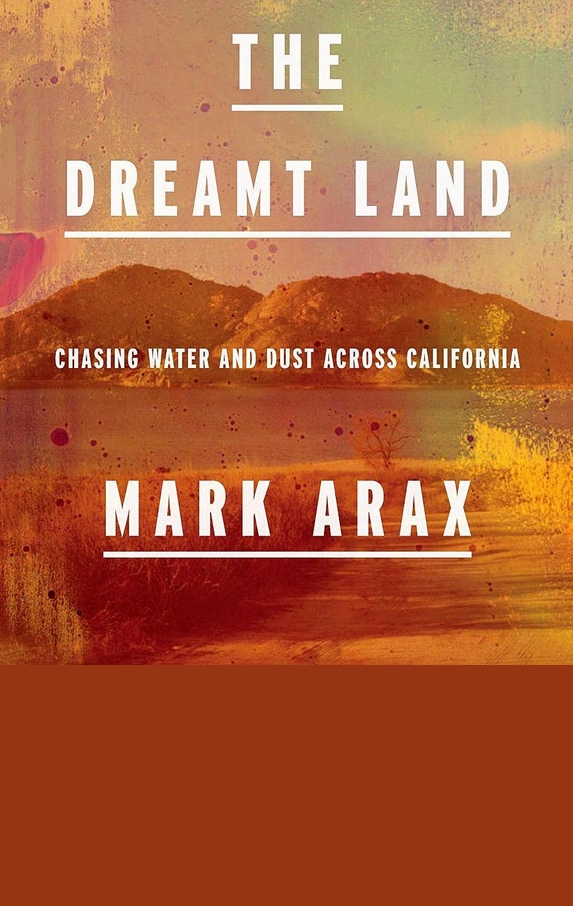

The Dreamt Land by Mark Arax

The Dreamt Land is a portrait of California’s Central Valley, where the control of water has defined everything from landscape to power (power in the form of hydroelectric energy and human control over who gets to shape and profit from the valley’s vast resources). Blending investigative journalism, history, and memoir, Arax explores how the state’s rivers, dams, and aqueducts turned desert into farmland and how that transformation came at immense ecological and social cost.

I’ve read several Arax books, but this one is my favorite. He’s one of the finest writers California has produced. He writes with passion and clarity, grounding his ideas in decades of firsthand experience with California’s land and water. His focus on the fertile Central Valley, where he grew up as a reporter and farmer’s son, gives the book both intimacy and authority, revealing how decisions about water shape not just the landscape but the people who depend on it. There are heroes and villains, plenty of the latter, and all of them unmistakably real. Yet Arax’s prose is so fluid and eloquent that you’ll keep reading not only for the story, but for the sheer pleasure of his writing.

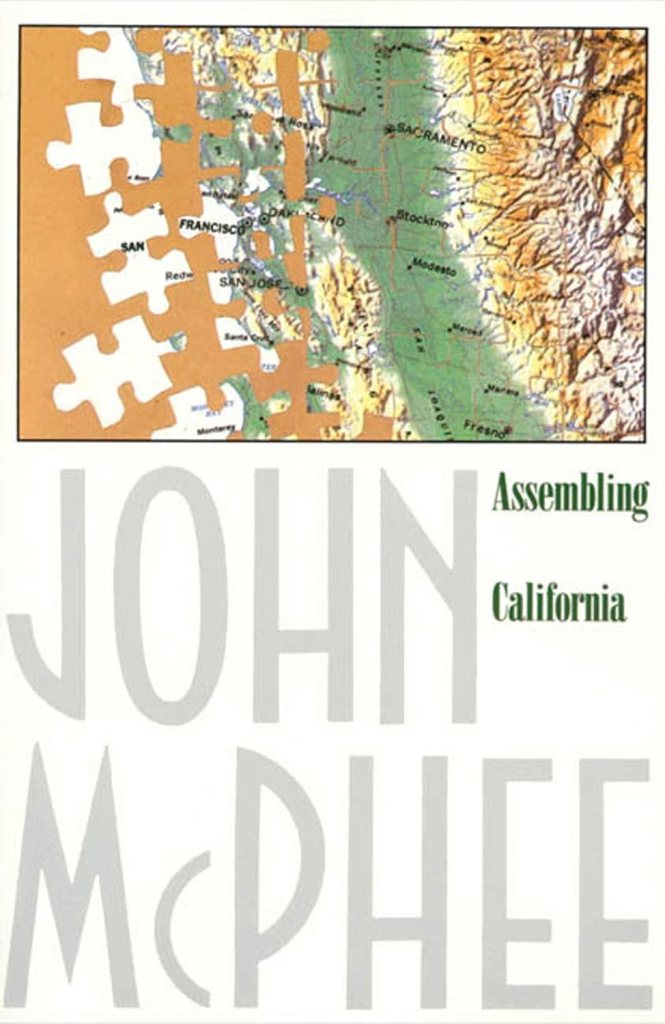

Assembling California by John McPhee (1993)

If you’re at all fascinated by California’s wild geology — and it truly is wild, just ask any geologist — this classic from one of the finest nonfiction writers alive is a must-read. McPhee takes readers on a geological road-trip through California, from the uplifted peaks of the Sierra Nevada to the fault-riven terrain of the San Andreas zone. He teams up with UC Davis geologist Eldridge Moores to explain how oceanic plates, island arcs, and continental blocks collided over millions of years to “assemble” the landmass we now call California. His prose is classic McPhee: clean, vivid, perhaps sometimes overly technical, as he turns terms like “ophiolite” and “batholith” into aspects of a landscape you can picture and feel.

What makes the book especially rewarding, especially for someone interested in earth systems, mapping, and the deep time, is how McPhee seamlessly links everyday places with deep-time events. You’ll read about gold-rush mining camps and vineyard soils, but all of it is rooted in tectonics, uplift, erosion, and transformation. I’ve gotten some of my favorite stories here on California Curated from the pages of this book. It can be ponderous at times, but you’ll not regret giving it a try.

The California Lands Trilogy by Obi Kaufman

The Forests of California (2020)

Obi Kaufman’s California Lands Trilogy is one of the most visually stunning and ambitious projects in California natural history publishing. Beginning with The Forests of California, the first of three volumes that reimagine the state not through its highways or cities but through its living systems, Kaufman invites readers to see California as a vast and interconnected organism, a place defined by its natural rhythms rather than human boundaries. Each book is filled with delicate watercolor maps and diagrams by the author himself. The result is part art book and part ecological manifesto, a celebration of the interconnectedness of California’s natural world. Kaufman’s talents as an artist are breathtaking. If he ever offered his original watercolors for sale, I’d be among the first in line to buy them. Taken together, the series forms a panoramic vision of the state’s natural environments.

That said, Kaufman’s books can be dense, filled with data, maps, and cross-references that reward slow reading more than quick browsing. If I’m honest, I tend to dip in and out of them, picking them up when I’m bored or need a break from the latest political bombshell. Every page offers something to linger over, whether it’s a river system painted like a circulatory map or a meditation on the idea of rewilding. For anyone fascinated by California’s natural systems, all Kaufman’s Field Atlases are invaluable companions endlessly worth revisiting.

The Enduring Wild: A Journey Into California’s Public Lands by Josh Jackson

My first job out of college was with the Department of the Interior in Washington, D.C., by far by the nation’s largest land management agency. A big part of that work involved traveling to sites managed by Interior across the country. I came to understand just how vast America’s public lands are and how much of that expanse, measured in millions of acres, is under the care of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

Josh Jackson takes readers on a road trip across California’s often overlooked public wilderness, focusing on the lands managed by the BLM, an agency once jokingly referred to as the Bureau of Livestock and Mining. He shows how these so-called “leftover lands” hold stories of geology, Indigenous presence, extraction, and conservation.

His prose and photography (he has a wonderful eye for landscapes) together invite the reader to slow down, look closely at the subtleties of desert mesas, sagebrush plains, and coastal bluffs, and reckon with what it means to protect places many people have never heard of. His use of the environmental psychology concept of “place attachment” struck a chord with me. The theory suggests that people form deep emotional and psychological bonds with natural places, connections that shape identity, memory, and a sense of belonging. As a frequent visitor to the Eastern Sierra, especially around Mammoth Lakes and Mono Lake, I was particularly drawn to Jackson’s chapter on that region. His account of the lingering impacts of the Mining Act of 1872, and how its provisions still allow for questionable practices today, driven by high gold prices, was eye-opening. I came away with new insights, which is always something I value in a book.

I should mention that I got my copy of the book directly from Josh, who lives not far from me in Southern California. We spent a few hours at a cafe in Highland Park talking about the value and beauty of public lands, and as I sat there flipping through the book, I couldn’t help but acknowledge how striking it is. Part of that comes from Heyday Books’ exceptional attention to design and production. Heyday also publishes Obi Kaufman’s work and they remain one of California’s great independent publishers. But much my appreciation for the book also comes from from Jackson himself, whose photographs are simply outstanding.

What makes this book especially compelling is its blend of adventure and stewardship. Jackson doesn’t simply celebrate wildness; he also lays out the human and institutional connections that shape (and threaten) these public lands, from grazing rights to mining to climate-change impacts. Some readers may find the breadth of landscapes and stories a little ambitious for a first book, yet the richness of the journey and the accessibility of the writing make it a strong addition for anyone interested in California’s endless conflict over land use: what should be used for extraction and what should be preserved? While I don’t fully agree with Jackson on the extent to which certain lands should be preserved, I still found the book a wonderful exploration of that question.

The Backyard Bird Chronicles by Amy Tan

Amy Tan’s The Backyard Bird Chronicles is a charming and unexpectedly personal journal of bird-watching, set in the yard of Tan’s Bay Area home. Tan is an excellent writer, as one would expect from a wildly successful novelist (The Joy Luck Club, among others). But she also brings a curiosity and wonder to the simple act of looking across one’s backyard. I loved it. Who among us in California doesn’t marvel at the sheer diversity of birds we see every day? And who hasn’t wondered about the secret lives they lead? A skilled illustrator as well as a writer, she studies the birds she observes by sketching them, using art as a way to closely connect with the natural world around her.

What begins as a peaceful retreat during the Covid catastrophe becomes an immersive odyssey of observation and drawing. Tan captures the comings and goings of more than sixty bird species, sketches their lively antics, as she reflects on how these small winged neighbors helped calm her inner world when the larger world felt unsteady.

My only quibble is that I was hoping for more scientific depth; the book is more of a meditation than a field study. Still, for anyone who loves birds, sketching, or the quiet beauty of everyday nature, it feels like a gentle invitation to slow down and truly look.

“Trees in Paradise” by Jared Farmer

California is the most botanically diverse state in the U.S. (by a long shot), home to more than 6,500 native plant species, about a third of which exist nowhere else on Earth. Jared Farmer’s Trees in Paradise: A California History follows four key tree species in California: the redwood, eucalyptus, orange, and palm. Through these examples, Farmer reveals how Californians have reshaped the state’s landscape and its identity. It’s rich in scientific and historical detail. I have discovered several story ideas in the book for California Curated and learned a great deal about the four trees that we still see everywhere in the California landscape.

In telling the story of these four trees (remember, both the eucalyptus and the palm were largely brought here from other places), Farmer avoids easy sentimentality or harsh judgment, instead exploring how the creation of a “paradise” in California came with ecological costs and profoundly shaped the state’s identity. While the book concentrates on those four tree categories, its detailed research and insight make it a compelling read for anyone interested in the state’s environment, history, and the ways people shape and are shaped by land.