California’s citrus industry confronted a deadly challenge, leading to a groundbreaking innovation in pest control.

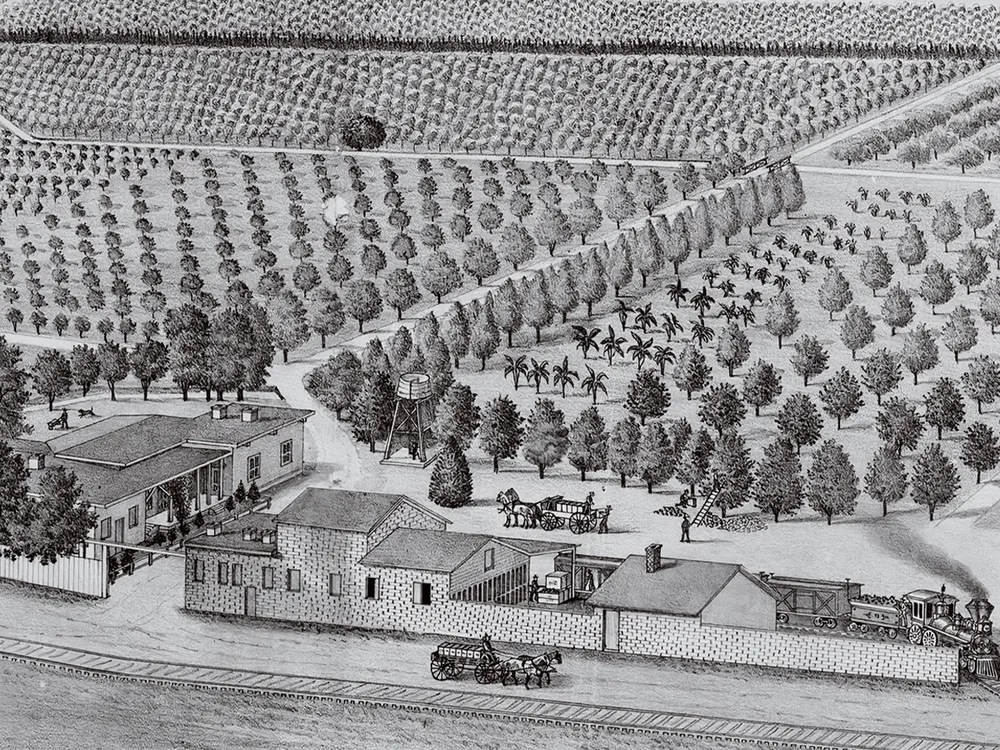

In the sun-drenched orchards of late 19th-century California, a crisis was unfolding that threatened to decimate the state’s burgeoning citrus industry. The culprit was a small sap-sucking insect native to Australia called the cottony cushion scale (Icerya purchasi). First identified in New Zealand in 1878, this pest had made its way to California by the early 1880s, wreaking havoc on citrus groves. The pest is believed to have arrived in the United States through the global trade of plants, a common vector for invasive species during the 19th century. As horticulture expanded globally, ornamental plants and crops were frequently shipped between countries without the quarantine measures we have today. Once established in the mild climate of California, the cottony cushion scale found ideal conditions to thrive, spreading rapidly and wreaking havoc on the citrus industry.

The cottony cushion scale infested trees with a vengeance, covering branches and leaves with a white, cotton-like secretion. This not only weakened the trees by extracting vital sap but also led to the growth of sooty mold on the honeydew excreted by the insects, further impairing photosynthesis. Growers employed various methods to combat the infestation, including washing trees with whale oil, applying blistering steam, and even detonating gunpowder in the orchards. Despite these efforts, the pest continued its relentless spread, causing citrus exports to plummet from 2,000 boxcars in 1887 to just 400 the following year. This decline translated to millions of dollars in lost revenue, threatening the livelihoods of countless farmers and jeopardizing the state’s citrus economy, which was valued at over $10 million annually (approx. $627 million in today’s dollars) during this period.

In 1885, the independent growers across Southern California banded together in response to the insect invasion and the broader difficulties facing citrus growers at the time, forming the state’s first fruit cooperative, which would later become Sunkist. Despite their efforts, homemade mixtures of kerosene, acids, and other chemicals failed to halt the relentless spread of Icerya purchasi. The pests, with an endless supply of citrus trees to feed on, continued to multiply unchecked. New laws mandated growers to uproot and burn infected orange trees, but the devastation was widespread. By 1888, real estate values, which had soared by 600 percent since 1877, had plummeted.

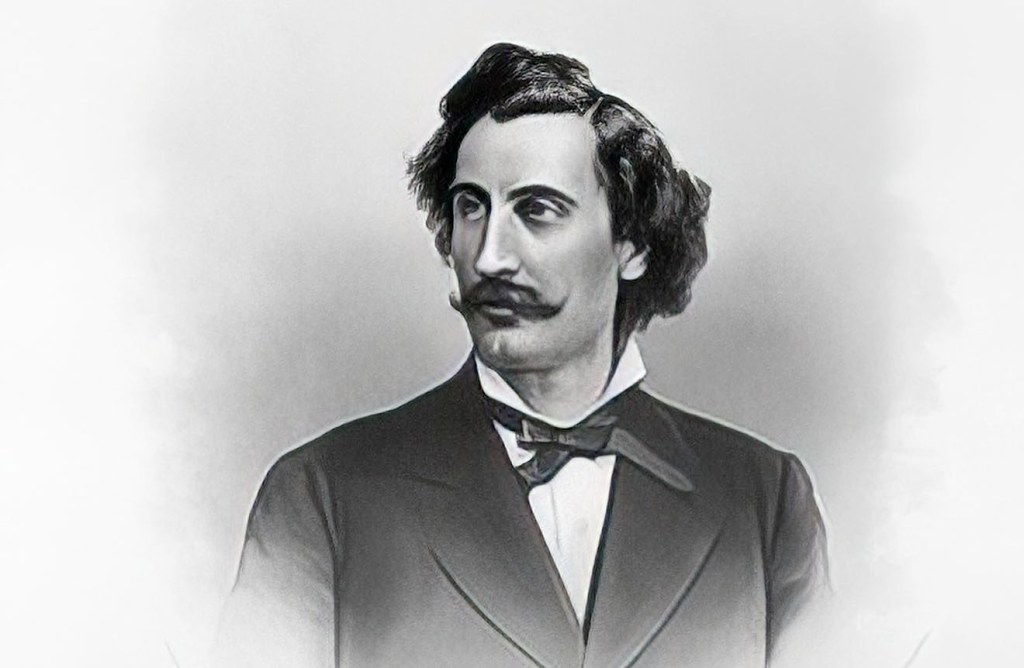

Enter Charles Valentine Riley, the Chief Entomologist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. A visionary in the field of entomology, Riley had previously attempted biological control by introducing predatory mites to combat grape phylloxera in France, albeit with limited success. Undeterred, he proposed a similar strategy for the cottony cushion scale crisis. In 1888, Riley dispatched his trusted colleague, a fellow entomologist named Albert Koebele, to Australia to identify natural enemies of the pest.

Interestingly, Valentine resorted to subterfuge to send an entomologist to Australia despite Congress’s objections. Lawmakers had prohibited foreign travel by the Agriculture Department to curb Riley’s frequent European excursions. However, Riley, well-versed in navigating political obstacles, cleverly arranged for an entomologist to join a State Department delegation heading to an international exposition in Melbourne.

Koebele’s expedition proved fruitful. He worked with Australian experts to locate the pest in its rare habitats along with its natural enemies, including a parasitic fly and approximately the Vedalia beetle. The vedalia beetle (Rodolia cardinalis) is a small ladybird with a voracious appetite for the cottony cushion scale. Koebele collected and shipped hundreds of these beetles back to California. Upon their release into infested orchards, the vedalia beetles rapidly established themselves, feasting on the scales and reproducing prolifically. Within months, the cottony cushion scale populations had diminished dramatically, and by 1890, the pest was largely under control across the state. This 1888-89 campaign marked the beginning of biological control in the United States, a strategy involving the introduction of natural predators to manage invasive pests.

In her 1962 classic Silent Spring, Rachel Carson described the Novius beetle’s work in California as “the world’s most famous and successful experiment in biological control.”

This was far from the last time California employed such measures. It became a relatively common practice to introduce new species to control those that posed threats to the state’s economically vital crops, but not always successfully.

In the 1940s, California introduced parasitic wasps such as Trioxys pallidus to control the walnut aphid, a pest threatening the state’s walnut orchards. These tiny wasps laid their eggs inside the aphids, killing them and dramatically reducing infestations, saving the industry millions of dollars. Decades later, in the 1990s, the state faced an invasive glassy-winged sharpshooter, a pest that spread Pierce’s disease in grapevines. (Interesting fact: The glassy-winged sharpshooter drinks huge amounts of water and thus pees frequently, expelling as much as 300 times its own body weight in urine every day.) To combat this, scientists introduced Gonatocerus ashmeadi, a parasitic wasp that targets the pest’s eggs. This biological control effort helped protect California’s wine industry from devastating losses.

While the introduction of the vedalia beetle was highly effective and hailed as a groundbreaking success, biological control efforts are not without risks, often falling prey to the law of unintended consequences. Although no major ecological disruptions were recorded in the case of the cottony cushion scale, similar projects have shown how introducing foreign species can sometimes lead to unforeseen negative impacts. For example, the cane toad in Australia, introduced to combat beetles in sugarcane fields, became a notorious ecological disaster as it spread uncontrollably, preying on native species and disrupting ecosystems. Similarly, the mongoose introduced to control rats in sugarcane fields in Hawaii also turned predatory toward native birds. These examples highlight the need for meticulous study and monitoring when implementing biological control strategies. Today, regulatory frameworks require rigorous ecological assessments to minimize such risks.

In the case of the Vedalia beetle, its precise and targeted predation led to a highly successful outcome in California. Citrus quickly became one of the state’s most dominant and profitable crops, helping to establish California as a leader in agricultural production—a position it continues to hold firmly today.

This groundbreaking use of biological control not only rescued California’s citrus industry but also established a global precedent for environmentally sustainable pest management. The success of the Vedalia beetle’s introduction showcased the power of natural predators in managing agricultural pests, offering an alternative to chemical pesticides. While pesticides remain widely used in California and across the world, this effort underscores the value of understanding ecological relationships, evolutionary biology, and the benefits of international scientific collaboration.

Visit the California Curated store on Etsy for original prints showing the beauty and natural wonder of California.

The story of the Vedalia beetle and the cottony cushion scale highlights human ingenuity and the effectiveness of nature’s own checks and balances. It stands as an early example of integrated pest management, a method that continues to grow and adapt to meet modern agricultural challenges. This successful intervention underscores the importance of sustainable practices in protecting both our food systems and the environment.