(We did a video about this story as well. We hope you watch! )

The story of corals in the modern age on this planet is one of near-total despair. I’ve done several stories on corals and have spent many hours diving reefs around the world, from the Mesoamerican Reef in Belize to the unbelievably robust and dazzling reefs in Indonesia. There are still some incredible places where corals survive, but they are becoming fewer and farther between. I don’t want to get too deep into all the statistics, but suffice it to say: scientists estimate that we have already lost about half of the world’s corals since the 1950s, and that number could rise to as much as 90 percent by 2050 if current rates of bleaching and die-offs continue.

What’s crazy is that we still don’t completely understand corals, or exactly why they are dying. We know that corals are symbionts with microscopic algae called zooxanthellae (pronounced zo-zan-THEL-ee). The corals provide cover, a place to live, and nutrients for the algae. In return, the algae provide sugars and oxygen through photosynthesis, fueling coral growth and reef-building. But when the planet warms, or when waters become too acidic, the relationship often collapses. The algae either die or flee the coral. Without that steady food source—what one scientist I interviewed for this story called “a candy store”—corals turn ghostly white in a process known as bleaching. If stressful conditions persist, they starve and die.

But why?

“We still have no idea, physiologically, in the types of environments where bleaching predominates, whether the animal is throwing them out because it’s going to try to survive, or whether the little tiny plants say to the animal, ‘look, we can’t get along in this environment, so we got to go somewhere else’” says Dr. Jules Jaffe, an oceanographer at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego in La Jolla, California, and the head of the Jaffe Laboratory for Underwater Imaging.

The Great Barrier Reef, once Earth’s largest living structure, has suffered five mass bleaching events since 1998, and vast stretches have become little more than graveyards of coral skeletons. The scale of this ecological disaster is almost unimaginable. And so scientists around the world are in a race to figure out what’s happening and how to at least try to slow down the bleaching events sweeping through nearly every major reef system.

One place where scientists are making small strides is at the Jaffe Lab, which I visited with my colleague Tod Mesirow and where researchers like Dr. Jaffe and Dr. Or Ben-Zvi have developed a new kind of underwater microscope that allows them to get close enough to corals to actually see the algae in action.

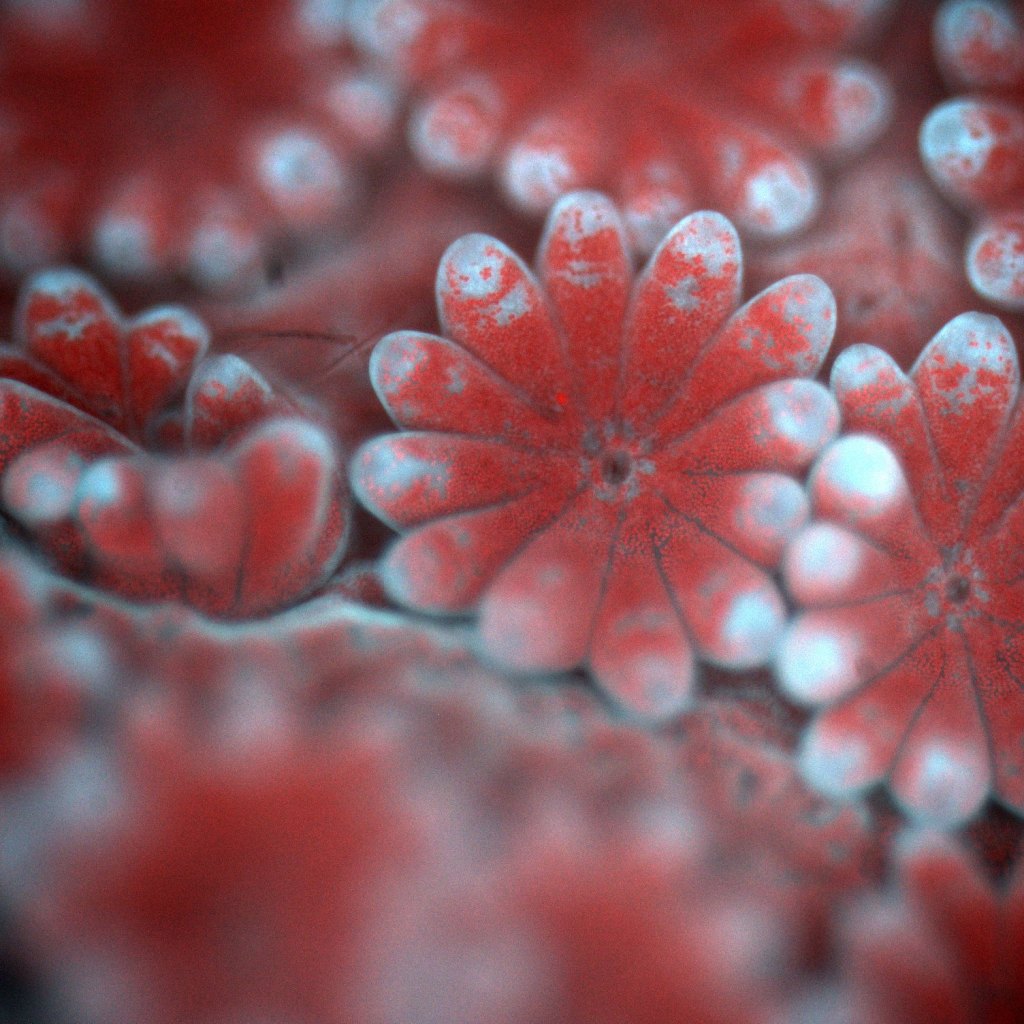

This is no small feat. Zooxanthellae are only about 5–10 microns across, about one-tenth the width of a human hair, and invisible to the naked eye. With the new microscope and camera system, though, they can be seen in astonishing detail. The lab has captured unprecedented behavior, including corals fighting with each other for space, fusing together, and even responding to invading algae.

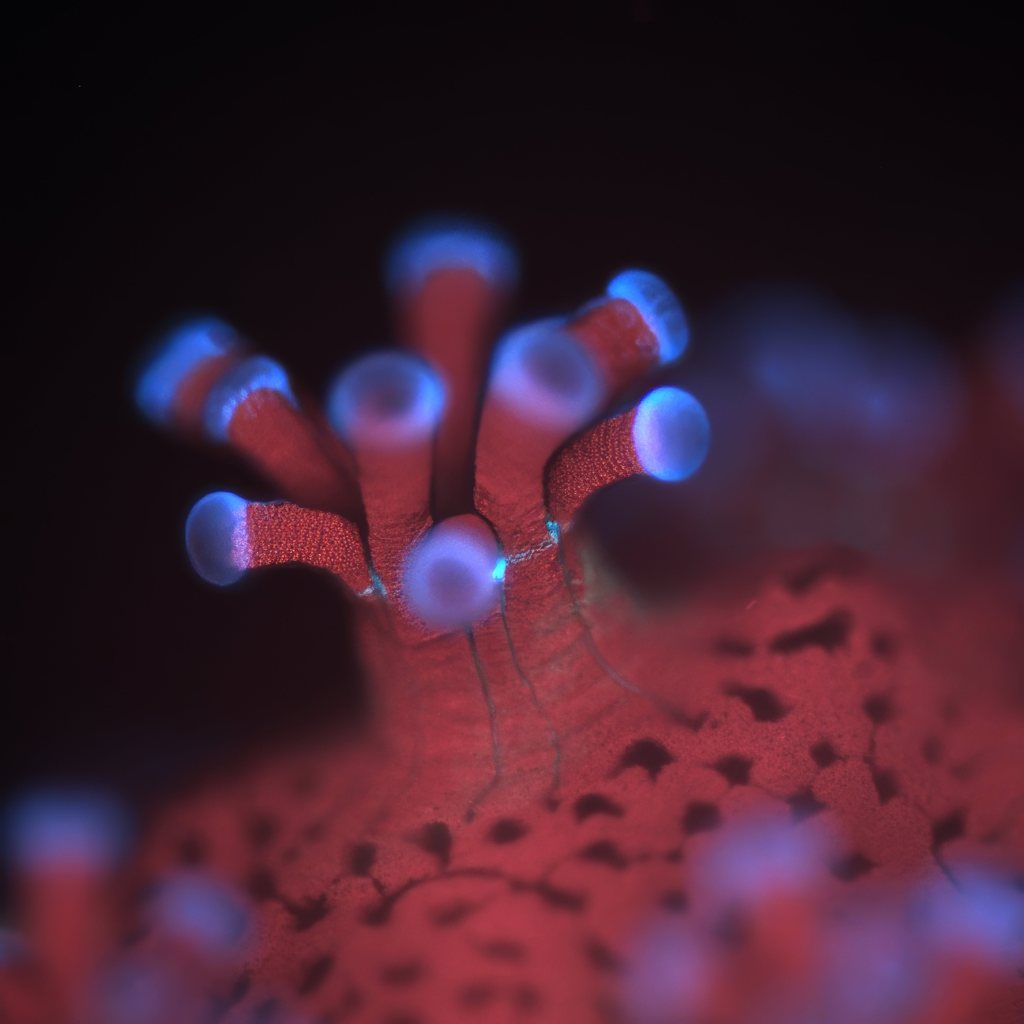

When I first reported on this imaging system years ago, it was still in its early stages. At the time, it was known as the BUM for Benthic Underwater Microscope. Since then, the Scripps team has added a powerful new capability: a pulsing blue light that lets them measure photosynthesis in real time. They call it pulse amplitude modulated light or PAM, and so now the system is known as the BUMP.

Here’s how it works: blue excitation light stimulates the algae’s chlorophyll, which then re-emits some of that energy as red fluorescence. By tracking how much of this red fluorescence is produced, researchers can calculate indices of photochemical efficiency, essentially how well the algae are converting light into energy for photosynthesis. This doesn’t give a direct count of sugars or photons consumed, but it does provide a reliable window into the health and productivity of the algae, and by extension, the coral itself.

What’s crucial is that all of this imaging takes place in situ—right in the ocean, on living reefs—rather than in the artificial setting of an aquarium or laboratory.

New tools are essential if we’re going to solve many of our biggest problems, and it’s at places like Scripps in California where scientists are hard at work creating instruments that help us see the world in entirely new ways. “There’s so much to learn about the ocean and its ecosystems, and my own key to understanding them is really the development of new instrumentation,” says Jaffe.

Dr. Ben-Zvi gave us a demonstration of how the system works in an aquarium holding several species of corals, including Stylophora, a common collector’s coral. She showed us the remarkable capabilities of the camera-microscope, which illuminated and brought into crisp focus the tiny coral polyps along with their algal partners. On the screen we watched them in real time, tentacles waving as they absorbed the flashes of light from the BUMP, appearing, almost, as if they were dancing happily.

(Photo: Erik Olsen)

What this new tool allows scientists to do is determine whether corals may be under stress from factors like warming seas, pollution, or disease. Ideally, these warning signs are detected before the corals expel their zooxanthellae and bleach. Researchers are also learning far more about the everyday behavior of corals: something rarely studied in situ, directly in the ocean.

That in-their-native-environment aspect of the work is crucial, because corals often behave very differently in aquariums than they do on wild reefs. That’s where this microscope promises to be a powerful tool: offering insights into how corals really live, fight, and respond to stress.

Of course, what we do once we document a reef under stress is another matter. Dr. Ben-Zvi suggests there may be possibilities for remediation, though she admits it’s difficult to know exactly what those are. Perhaps reducing pollution, limiting fishing, or cutting ship traffic in vulnerable areas could help. But given that we seem unable—or unwilling—to stop the warming of the seas, these measures can feel like stopgaps rather than solutions. Still, knowledge is the foundation for any action, and this new tool is a breakthrough for coral imaging. If deployed widely, it could generate an invaluable dataset for researchers around the globe. The scientists behind it even hope to build multiple systems, perhaps commercializing them, to vastly expand the reach of this kind of monitoring.

But even Jaffe concedes it may already be too late: “Could a world exist without corals? Yeah, I think so,” he said. “It would be sad, but it’s going that way.”

All the same, the images the tool produces are breathtaking, and at the very least, they might jolt people into realizing that this is a crisis worth trying to solve. If we can’t, then future generations will be left only with these hauntingly beautiful images to remember the diverse and gorgeous animals that once flourished along the edges of the sea.

Is that valuable? Yes, but not nearly as valuable as saving the living reefs themselves. Dr. Jaffe told us,

“I’m on a mission to help people feel empathy toward the creatures of the sea. At the same time, we need to learn just how beautiful they are. For me, the combination of beauty and science has been at the heart of my life’s work.”

His words capture the spirit of this research. The underwater microscope isn’t just a scientific instrument. It’s a lens into a hidden world, one that may inspire people to care enough to act before it’s gone. Too bad the clock is ticking so fast.

(We did a video about this story as well. We hope you watch! )