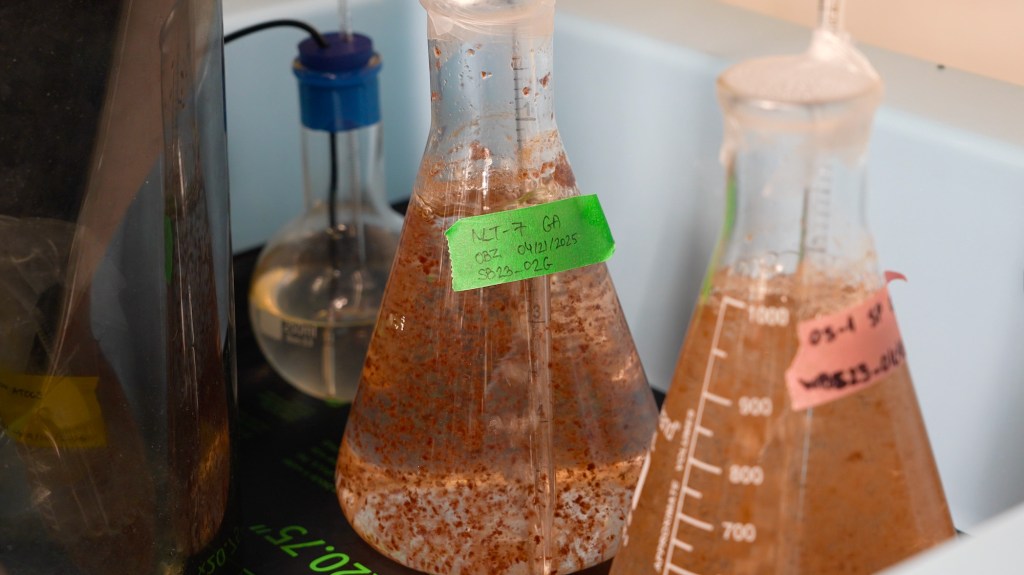

Inside a long, brightly lit basement lab at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego, a large aquarium filled with live corals sits against the wall, the vibrant shapes and colors of the coral standing out against the otherwise plain white surroundings. Nearby, in a side alcove, dozens of glass flasks bubble with aerated water, each holding tiny crimson clusters of seaweed swirling in suspension, resembling miniature lava lamps. These fragile red fragments, born in California and raised under tightly controlled conditions, are part of a global effort to harness seaweed to fight climate change.

Cattle and other ruminant livestock are among the largest contributors to methane emissions worldwide, releasing vast amounts of the gas through digestion and eructation. Burps, not farts. The distinction is not especially important, but it matters because critics of climate science often mock the idea of “cow farts” driving climate change. In reality, the methane comes primarily from cow burps, not flatulence.

But I digress.

Globally, livestock are responsible for roughly 14 percent of all human-induced greenhouse gases, with methane from cattle making up a significant portion of that total. The beef and dairy industries alone involve more than a billion head of cattle, producing meat and milk that fuel economies but also generating methane on a scale that rivals emissions from major industrial sectors. Because methane is so potent, trapping more than 80 times as much heat as carbon dioxide over a 20-year period, the livestock industry’s footprint has become a central focus for climate scientists searching for solutions.

Enter Jennifer Smith and her colleagues at the Smith Lab at Scripps in beautiful La Jolla, California. Their team is tackling urgent environmental challenges, from understanding coral die-offs to developing strategies that reduce greenhouse gas emissions, among them, the cultivation of seaweed to curb methane from cattle.

The seaweed species is Asparagopsis taxiformis. Native to tropical and warm temperate seas and found off the coast of California, in fact right here off the coast in San Diego, it produces natural compounds such as bromoform that interfere with the microbes in a cow’s stomach that generate methane gas, significantly reducing the production of methane and, of course, it’s exhalation by the animals we eat. It turns out the seaweed, when added to animal feed can be very effective:

“You need to feed the cows only less than 1% of their diet with this red algae and it can reduce up to 99% of their methane emissions,” said Dr. Or Ben Zvi, an Israeli postdoctoral researcher at Scripps who studies both corals and seaweeds.

Trials in Australia, California, and other regions have shown just how potent this seaweed can be. As Dr. Ben Zvi indicated, even at tiny doses, fractions of a percent of a cow’s feed, other studies have shown that it can reduce methane by 30 to 90 percent, depending on conditions and preparation. Such results suggest enormous potential, but only if enough of the seaweed can be produced consistently and sustainably.

“At the moment it is quite labor intensive,” says Ben Zvi. “We’re developing workflows to create a more streamlined and cost-effective industry.”

Which explains to bubbling flasks around me now.

The Smith lab here at Scripps studies every stage of the process, from identifying which strains of Asparagopsis thrive locally to testing how temperature, light, and carbon dioxide affect growth and bromoform content. Dr. Ben Zvi is focused on the life cycle and photosynthesis of the species, refining culture techniques that could make large-scale cultivation possible. At Scripps, environmental physiology experiments show that local strains grow best at 22 to 26 °C and respond well to elevated CO₂, information that could guide commercial farming in Southern California.

The challenges, however, are considerable. Wild harvesting cannot meet demand, and cultivating seaweed at scale requires reliable methods, stable yields, and affordable costs. Bromoform content varies widely depending on strain and growing conditions, so consistency remains an issue. Some trials have noted side effects such as reduced feed intake or excess mineral uptake, and long-term safety must be established since we’re talking about animals that we breed and raise to eat.

“It’s still a very young area, and we’re working on the legislation of it,” says Ben Zvi. “We need to make it legal to feed to a cow that eventually we either drink their milk or eat their meat. We need for it to be safe for human consumption.”

And, of course, large-scale aquaculture raises ecological questions, from nutrient demands and pollution to the fate of volatile compounds like bromoform.

To overcome these obstacles, collaborations are underway. UC San Diego and UC Davis have launched a pilot project under the UC Carbon Neutrality Initiative to test production methods and carbon benefits. In 2024, CH4 Global, a U.S.-based company with operations in New Zealand and Australia that develops seaweed feed supplements to cut livestock methane, partnered with Scripps to design cultivation systems that are efficient, inexpensive, and scalable. Within the Smith Lab, researchers are continuing to probe the biology of Asparagopsis, mapping its genetics, fine-tuning its culture, and testing ways to maximize both growth and methane-suppressing compounds.

At a time when university-based science faces immense pressures, the Smith Lab at Scripps provides a glimpse of research that is making a real impact. The coral tanks against the wall belong to another project at the lab, and we have another story coming soon about the research that readers will find very interesting, but the bubbling flasks in the alcove reveal how breakthroughs often start with small details. In this case, the discovery that a chemical in a widely available seaweed could have such a dramatic, and apparently harmless, effect on the methane that animals make in their guts. These modest but powerful steps are shaping solutions to global challenges, and California, with its wealth of scientific talent and institutions, remains at the forefront. It is one of many other stories we want to share, from inside the labs to the wide open spaces of the state’s natural landscapes.