I just got back from a filming assignment in California’s Central Valley. That drive up I-5 and Highway 99 is always a strange kind of pleasure. After climbing over the Grapevine, the landscape suddenly flattens and opens into a vast plain where farmland and dry earth stretch endlessly in every direction. A pumpjack. A dairy farm. Bakersfield. There’s a mysterious, almost bleak beauty to it. Then come the long stretches where the view shifts from dust to trees: pistachio trees. Especially through the San Joaquin Valley, miles of low, gray-green orchards extend to the horizon. At various points, I busted out a drone and took a look, and as far as I could see, it was pistachio trees. A colorful cluster of pistachios hung from a branch and I picked on and peeled off the fruity outer layer. There was that familiar nut with the curved cracked opening. The smiling nut.

California now grows more pistachios than any place on Earth, generating nearly $3 billion in economic value in the state. Nearly every nut sold in the United States, and most shipped abroad, comes from orchards in the Central Valley. The state produces about 99 percent of America’s pistachios, and the U.S. itself accounts for roughly two-thirds of the global supply. And that all happened relatively quickly.

When the U.S. Department of Agriculture began searching for crops suited to the arid West in the early 1900s, the pistachio was an obvious choice. In 1929, a USDA plant explorer named William E. Whitehouse traveled through Persia collecting seeds. Most failed to germinate, but one, gathered near the city of Kerman, produced trees that thrived in California’s dry heat. The resulting Kerman cultivar, paired with a compatible male variety named Peters, became the foundation of the modern industry. Every commercial orchard in California today descends from those early seeds.

For decades, pistachios were sold mainly to immigrants from the Middle East and Mediterranean. It wasn’t until the 1970s that California growers, backed by UC Davis researchers and improved irrigation, began planting on a large scale. By the early 1980s, they had found their perfect home in the southern San Joaquin Valley—Kern, Tulare, Kings, Fresno, and Madera Counties—a region with crazy hot summers, crisp winters…according to researchers, the kind of stress the trees need to flourish.

Then came The Wonderful Company, founded in 1979 by Los Angeles billionaires Stewart and Lynda Resnick. From a handful of orchards, they built an empire of more than 125,000 acres, anchored by a vast processing plant in Lost Hills. Their bright-green “Wonderful Pistachios” bags and silly “Get Crackin’” ads turned what was once an exotic import into a billion-dollar staple.

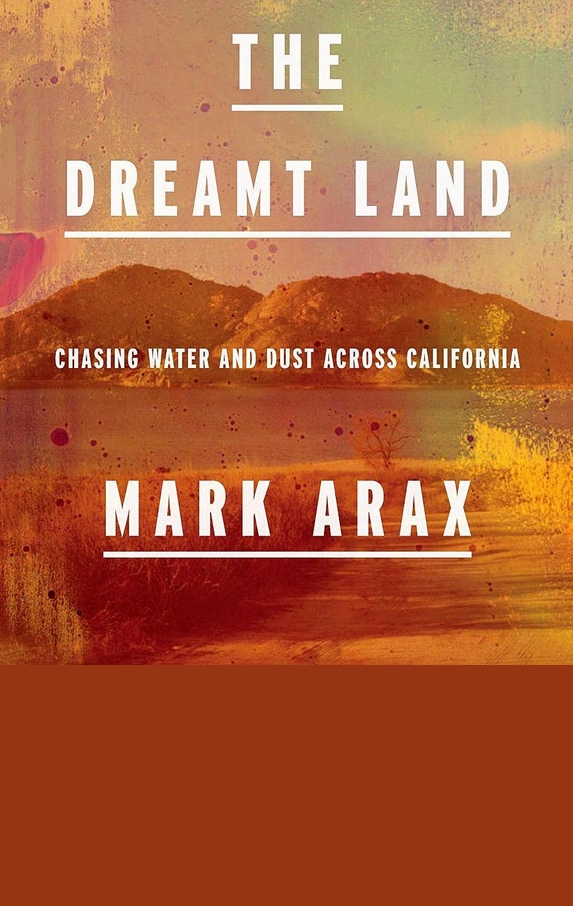

But the company’s success is riddled with controversy. Mark Arax wrote a scathing piece a few years ago about the Resnicks in the (now, sadly defunct) California Sunday Magazine. The Resnicks have been criticized for their immense control over California’s water and agriculture, using their political influence and vast network of wells to secure resources that many see as public goods. Arax described how the couple transformed the arid west side of the San Joaquin Valley into a private agricultural empire, while smaller farmers struggled through droughts and groundwater depletion. “Most everything that can be touched in this corner of California belongs to Wonderful,” Arax writes. (Side note: Arax’s The Dreamt Land made our recent Ten Essential Books About California’s Nature, Science, and Sense of Place.)

And yes, pistachios have been immensely profitable for the Resnicks. Arax write: “All told, 36 men operating six machines will harvest the orchard in six days. Each tree produces 38 pounds of nuts. Typically, each pound sells wholesale for $4.25. The math works out to $162 a tree. The pistachio trees in Wonderful number 6 million. That’s a billion-dollar crop.”

Alas, California’s pistachio boom carries contradictions. The crop is both water-hungry and drought-tolerant, a paradox in a state defined by water scarcity. Each pound of nuts requires around 1,400 gallons of water, less than almonds, but still a heavy draw from aquifers and canals. Pistachio trees can survive in poor, salty soils and endure dry years better than most crops, yet once established, they can’t be left unwatered without risking long-term damage. Growers call them a “forever crop.” Plant one, and you’re committed for decades.

The pistachio has reshaped the Central Valley’s landscape. Once a patchwork of row crops and grazing land, vast acres are now covered in pistachio orchards, the ones I was recently driving through.

Pretty much everyone growing anything in California – pistachios, almonds, strawberries (especially strawberries) – can thank the University of California at Davis for help in improving their crops and managing problems like climate change and pests. Davis is a HUGE agricultural school and has many programs to help California farmers.

In the case of the pistachio, recent research at UC Davis has shed new light on the tree’s genetic makeup. Scientists there recently completed a detailed DNA map of the Kerman variety, unlocking the genetic controls of kernel size, flavor compounds, shell-splitting behaviour and climate resilience. The idea is to help growers by making pistachios adapt to hotter, drier conditions. UC Davis is now one of the world’s leading centers for pistachio and nut science.

Here’s something I’ll bet you didn’t know: pistachios can spontaneously combust. Pistachios are rich in unsaturated oils that can slowly oxidize, generating enough heat to ignite large piles if ventilation is poor. Shipping manuals classify them as a “spontaneous-combustion hazard”, a rare but real risk for warehouses and freighters hauling tons of California pistachios across the world. Encyclopedia Britannica notes they are often treated as “dangerous cargo” at sea.

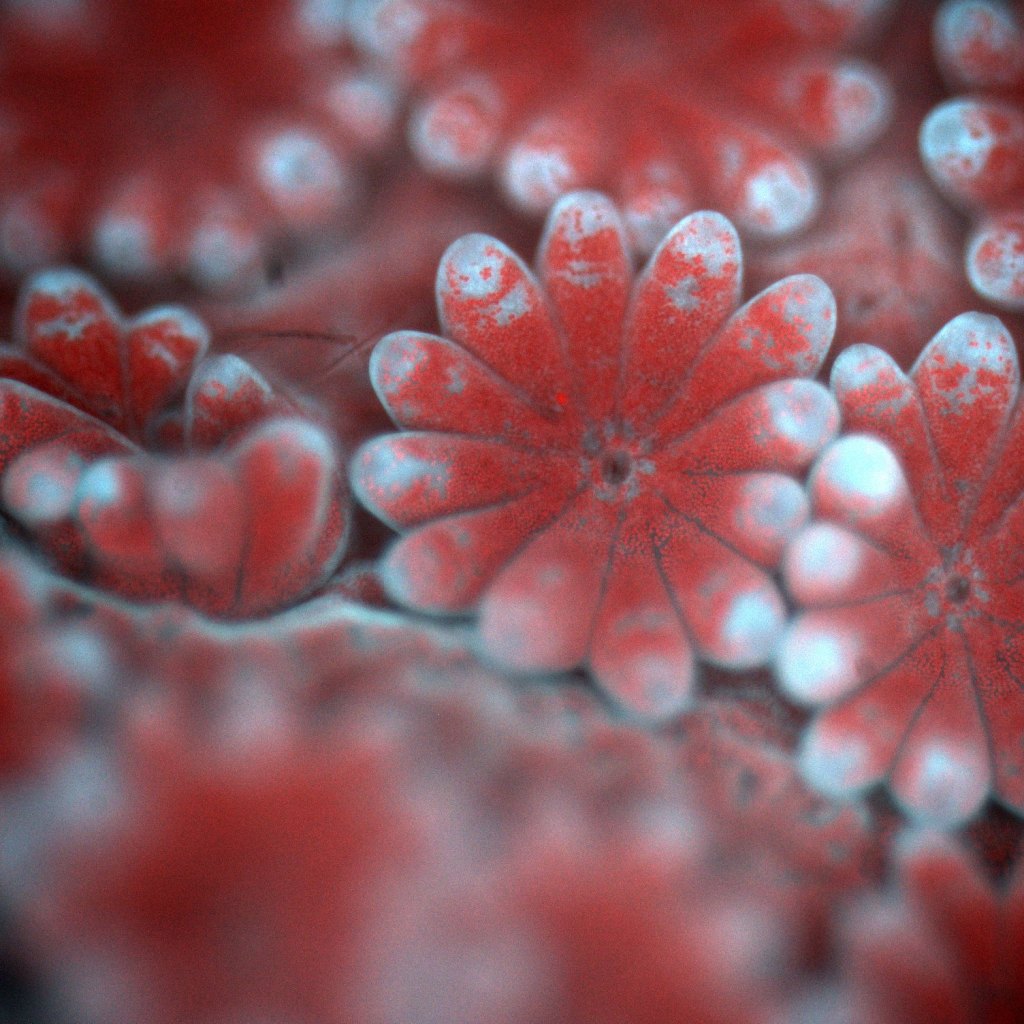

Now, some pistachio biology: The pistachio is dioecious, meaning male and female flowers grow on separate trees. Almonds are not. Farmers plant one male for every eight to ten females, relying on wind for pollination. The trees follow an alternate-bearing cycle, heavy one season, light the next. They don’t produce a profitable crop for about seven years, but once mature, they can keep producing for half a century or more.

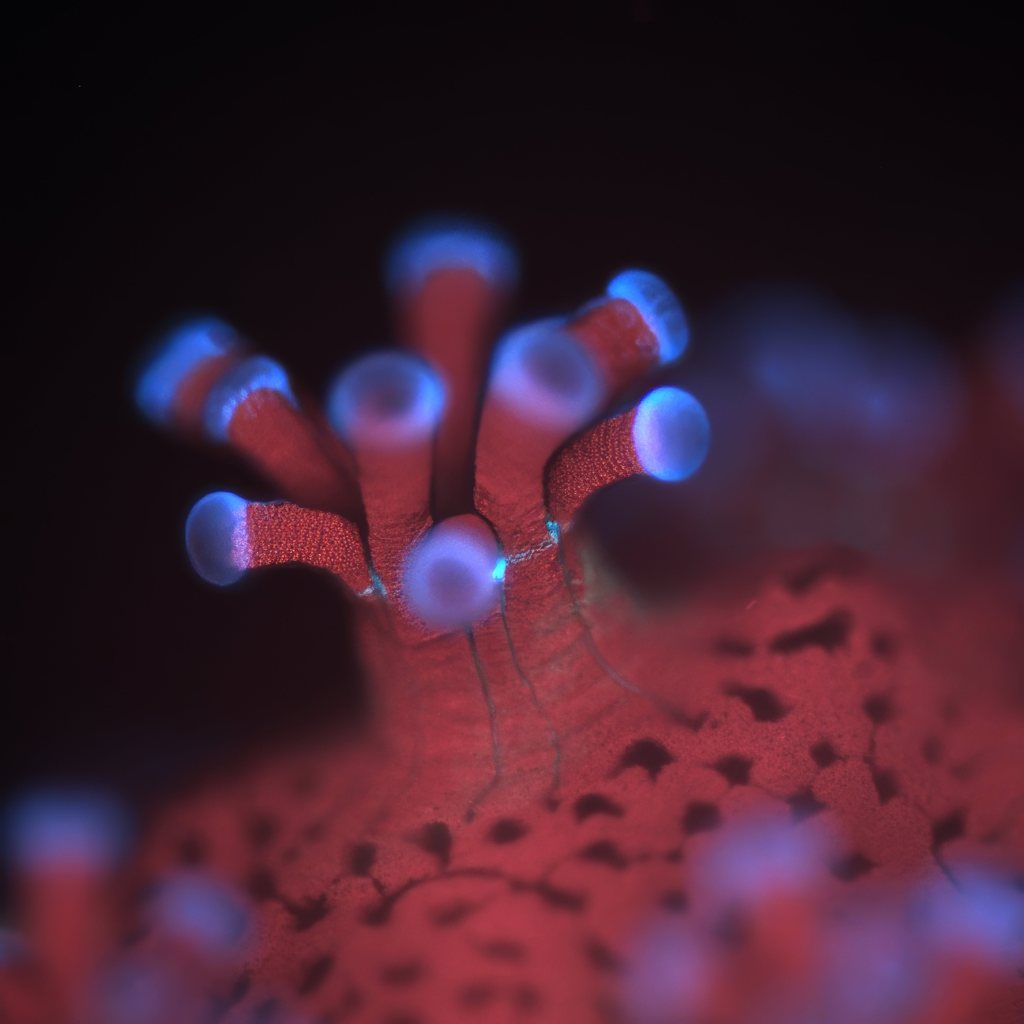

Another strange quirk of pistachios is that they are green and, if you look closely, streaked with a faint violet hue. The green comes from chlorophyll, the same pigment that gives leaves their color, which in pistachios lingers unusually long into the nut’s maturity. Most seeds lose chlorophyll as they ripen, but pistachios retain it, especially in the outer layers of the kernel. The purple tint, meanwhile, comes from anthocyanins, antioxidant pigments also found in blueberries and grapes.

As I walked among the pistachio trees recently, I marveled at how alone I was on one of the dirt roads off Highway 99. Not a soul in sight, only the hum of irrigation pumps and the rattle of dry leaves in the breeze. I like to write about the things we all see and experience in California but rarely stop to look at closely. Pistachios are one of those things. If you’ve ever driven through the San Joaquin Valley, you’ve seen how the landscape stretches for miles in orderly rows of pistachio trees. It’s easy to forget, amid the fame of Silicon Valley and Hollywood, that so much of California’s wealth still comes from the land itself, from agriculture and other extractive industries. The pistachio boom is a story of astonishing scale, but it’s also riven with the contradictions and complexities of modern California itself, where innovation and exploitation often grow from the same soil.