When I started this Website, my hope was to share California’s astonishing range of landscapes, laboratories, and ideas. This state is overflowing with scientific discovery and natural marvels, and I want readers to understand, and enjoy, how unusually fertile this state is for discovery. If you’re not curious about the world, then this Website is definitely not for you. If you are, then I hope you get something out of it when you step outside and look around.

I spend a lot of time in the California mountains and at sea, and I am endlessly amazed by the natural world at our doorstep. I am also fascinated by California’s industrial past, the way mining, oil, and agriculture built its wealth, and how it later became a cradle for the technologies and industries now driving human society forward. Of course, some people see technologies like gene editing and AI as existential risks. I’m an optimist. I see tools that, while potentially dangerous, used wisely, expand what is possible.

Today’s story turns toward technology, and one breakthrough in particular that has reshaped the modern world. It is not just in the phone in your pocket, but in the computers that train artificial intelligence, in advanced manufacturing, and in the systems that keep the entire digital economy running. The technology is extreme ultraviolet lithography (EUV). And one of the most important points I want to leave you with is that the origins of EUV are not found in Silicon Valley startups or corporate boardrooms but in California’s national laboratories, where government-funded science made the impossible possible.

This article is not a political argument, though it comes at a time when government funding is often questioned or dismissed. My purpose is to underscore how much California’s national labs have accomplished and to affirm their value.

This story begins in the late 1980s and 1990s, when it became clear that if Moore’s Law was going to hold, chipmakers would need shorter and shorter wavelengths of light to keep shrinking transistors. Extreme ultraviolet light, or EUV, sits way beyond the visible spectrum, at a wavelength far shorter than ordinary ultraviolet lamps. That short wavelength makes it possible to draw patterns on silicon at the tiniest scales…and I mean REALLY tiny.

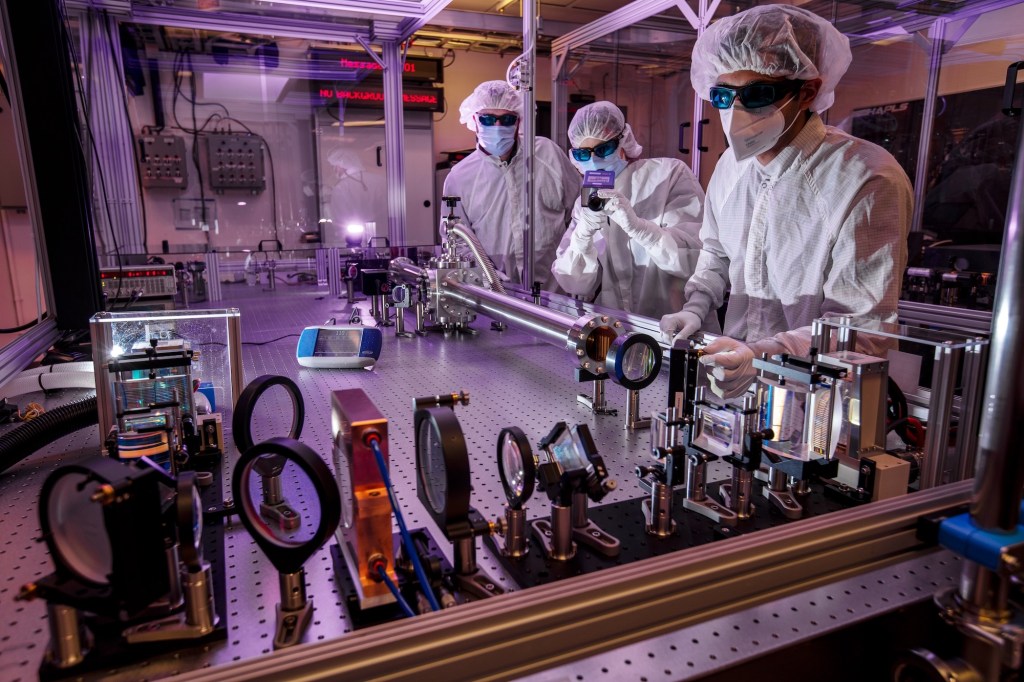

At Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, researchers with expertise in lasers and plasmas were tasked with figuring out how to generate a powerful, reliable source of extreme ultraviolet light for chipmaking. Their solution was to fire high-energy laser pulses at microscopic droplets of tin, creating a superheated plasma that emits at just the right (tiny) wavelength for etching circuits onto silicon.

Generating the light was only the first step. To turn it into a working lithography system required other national labs to solve equally daunting problems. Scientists at Berkeley’s Center for X Ray Optics developed multilayer mirrors that could reflect the right slice of light with surprising efficiency. A branch of Sandia National Laboratories located in Livermore, California, worked on the pieces that translate light into patterns. So, in all: Livermore built and tested exposure systems, Berkeley measured and perfected optics and materials, and Sandia helped prove that the whole chain could run as a single machine.

It matters that this happened in public laboratories. The labs had the patient funding and the unusual mix of skills to attempt something that might not pay off for many years. The Department of Energy supported the facilities and the people. DARPA helped connect the labs with industry partners and kept the effort moving when it was still risky. There was no guarantee that the plasma would be bright enough, that the mirrors would reflect cleanly, or that the resists (the light-sensitive materials coated onto silicon wafers) would behave. The national labs could take that on because they are designed to tackle long horizon problems that industry would otherwise avoid.

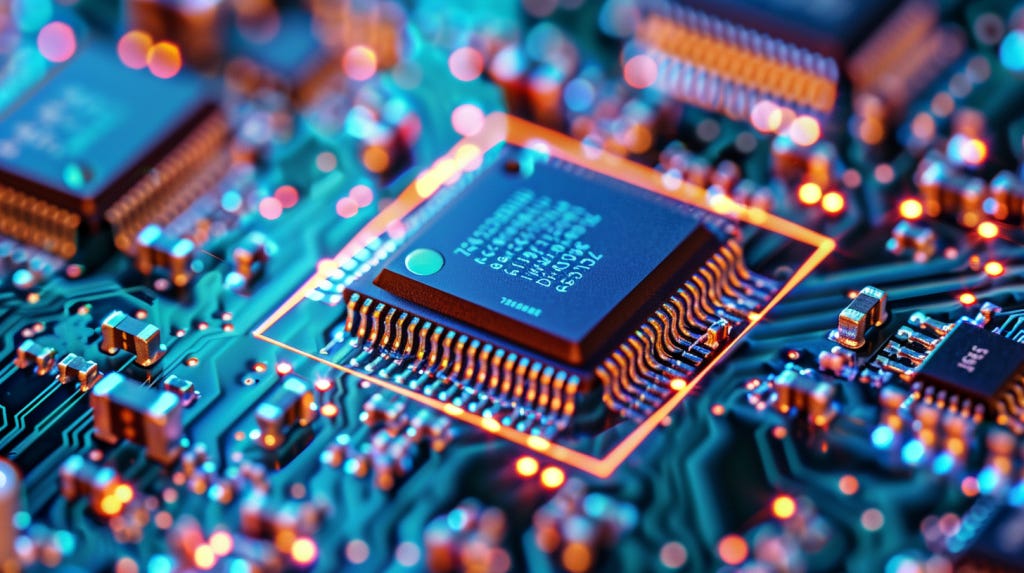

Only later did private industry scale the laboratory breakthroughs into the giant tools that now anchor modern chip factories. The Dutch company ASML became the central player, building the scanners that move wafers with incredible precision under the fragile EUV light. Those systems are now capable of etching transistor features as small as 5 nanometers…5 billionths of a meter. You really can’t even use the “smaller than a human hair” comparison here since human hair variation is so large at this scale as to render that comparison kind of useless. However, many people still do.

The ASML machines are marvels of tech and engineering. Truly amazing feats human design. And they integrate subsystems from all over the world: Zeiss in Germany manufactures the mirrors, polished to near-atomic perfection, while San Diego’s Cymer (now part of ASML) supplies the laser-driven plasma light sources. The technology is so complex that a single scanner involves hundreds of thousands of components and takes months to assemble.

It was TSMC and Samsung that then poured billions of dollars into making these tools reliable at scale, building the factories that now turn EUV light into the chips powering AI and smartphones and countless other devices. Trillions of dollars are at stake. Some say the fate of humanity lies in balance should Artificial General Intelligence eventually emerge (again, I don’t say that, but some do). All of this grew from the ingenuity and perseverance, along with the public funding, that sustained these California labs.

It’s disappointing that many of the companies profiting most from these technological breakthroughs are not based in the United States, even though the core science was proven here in California. That is fodder for a much longer essay, and perhaps even for a broader conversation about national industrial policy, something the CHIPS Act is only beginning to deal with.

However, if you look closely at the architecture of those monster machines, you can still see the fingerprints of the California work. A tin plasma for the light. Vacuum chambers that keep the beam alive. Reflective optics that never existed at this level before EUV research made them possible.

We often celebrate garages, founders, and the venture playbook. Those are real parts of the California story. This is a different part, just as important. The laboratories in Livermore, Berkeley, and Sandia are public assets. They exist because voters and policymakers chose to fund places where hard problems can be worked on for as long as it takes. The payoff can feel distant at first, then suddenly it is in your pocket. Like EUV. Years of quiet experiments on lasers, mirrors, and materials became the hidden machinery of the digital age.