If you’ve been reading this newsletter for a while, you already know I’m obsessed with submarines and undersea life. I believe we’re at the beginning of a new era of ocean discovery, driven by small personal submersibles, remotely operated vehicles (ROVS), and autonomous explorers (AUVs) that can roam the deep on their own. Add AI into the mix, and our ability to see, map, and understand the ocean is about to expand dramatically.

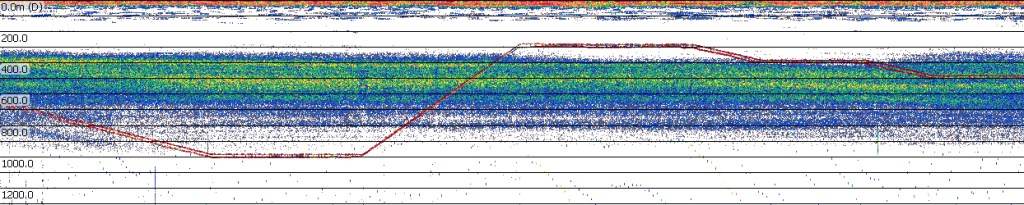

One phenomenon we are only beginning to fully understand also happens to be one of the most extraordinary animal events on Earth. It unfolds every single night, just a few miles offshore, in a region known as the ocean twilight zone about 650 to 3,300 feet below the ocean surface. Twice a day, billions of tons of marine organisms, from tiny crustaceans to massive schools of squid, traverse the water column in what researchers call the Diel Vertical Migration (DVM), the largest mass migration of animals on Earth. A heaving, planetary-scale pulse of biomass rising and falling through the dark.

It happens everywhere, in every ocean. But California is special for several reasons. California’s cold, southward-flowing current and seasonal upwelling flood coastal waters with nutrients that feed dense plankton blooms. These blooms provide food for thick layers of migrating animals. California has one of the most robust and productive ocean ecosystems on the planet. (Take a read of the piece I did about life on some of our oil rigs.) When you add Monterey Canyon into the mix, which funnels and concentrates life, this global phenomenon becomes more compressed and visible. In fact, with Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) based at Moss Landing near the head of the canyon, Monterey Bay has become one of the most intensively studied midwater ecosystems on the planet.

This “tidal cycle of shifting biomass” is not driven by gravity, but by the rising and setting sun. Animals rise by the trillions during the evening to escape predation, then settle during the day, when light would otherwise make them visible to hungry predators.

The discovery of this phenomenon reads like a Tom Clancy novel and took place just off our coast. During World War II, U.S. Navy sonar operators working off San Diego and the Southern California Bight began detecting what looked like a “false seafloor” hovering 300 to 500 meters down during the day, only to sink or vanish each night. The mystery lingered for years, until the late 1940s, when scientist Martin Johnson and others at Scripps Institution of Oceanography showed that the phantom bottom was not seafloor, but vast layers of living animals rising and falling with the sun. We now know this as the Deep Scattering Layer (DSL), so named because the gas-filled swim bladders of millions of small fish, primarily lanternfish which number into the quadrillions around the globe, reflect sonar pings like a solid wall.

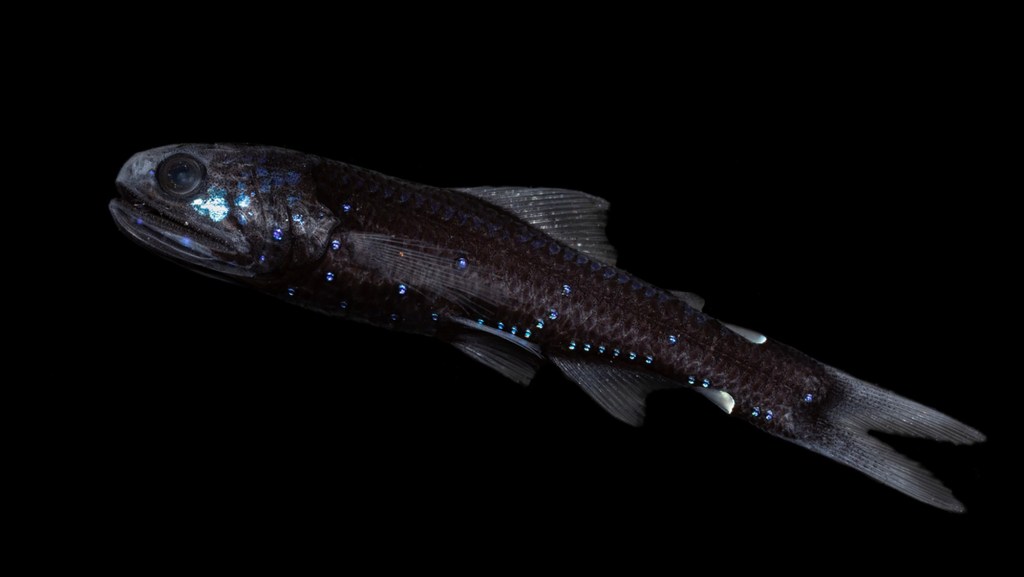

So let’s talk about those amazing lanternfish, aka myctophids, a species that many peole have likely never heard of. These small fish may make up as much as 65 percent of all deep-sea fish biomass and are a major food source for whales, dolphins, salmon, and squid. They use tiny light organs called photophores to match faint surface light, a camouflage strategy known as counterillumination that helps hide them from predators below. These are just one of the many different species that inhabit the twilight zone as part of the DVM.

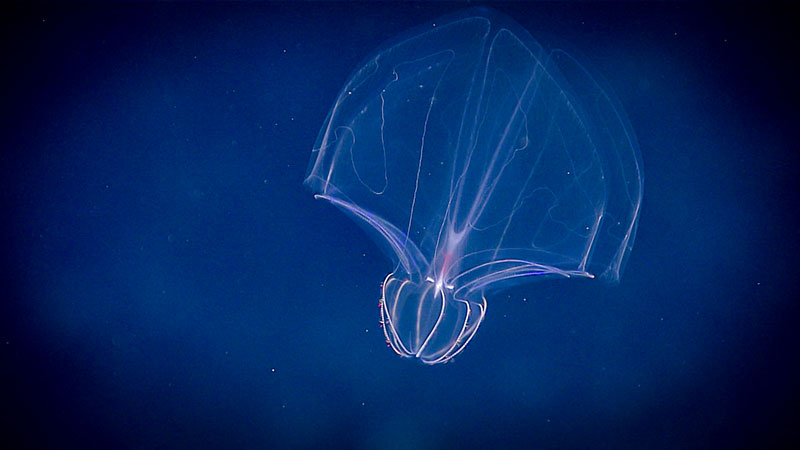

Monterey Bay is arguably the world’s most important laboratory for DVM research, thanks to the Monterey Canyon, and several ground-breaking discoveries have come out of MBARI. For example, scientists at MBARI, including the legendary Bruce Robison, have used ROVs to document what they call “running the gauntlet,” when these migrators pass through layers of hungry, waiting predators. They encounter giant siphonophores with stinging tentacles, squids snag lanternfish, and giant larvaceans that build sprawling mucus “houses” that trap smaller animals. It’s like an epic battle scene out of Lord of the Rings, every single day.

This migration is also a key part of the ocean’s carbon cycle, which includes a scientific process known as the biological pump. When larger animals eat carbon-rich plankton at the surface, they eventually defecate all that carbon into the water, aka the “active transport” mechanism. Much of that carbon sinks to the bottom, sequestering it for decades or even centuries. In some regions, DVM accounts for one-third of the total carbon transport to the deep ocean. MBARI has a very interesting, long-term deep-ocean observatory called the Station M research site and observatory located nearly 12,000 feet below the surface off Santa Barbara. This site has been continuously monitored for more than three decades to track how organic matter produced near the surface eventually reaches the abyssal seafloor and feeds deep communities. I did a video about it for MBARI a few years ago.

Other cutting-edge technology is being brought to bear as well to help us better understand what life exists in the deep waters off California. A UC San Diego study shows that we can now use low-volume environmental DNA (eDNA) to detect the genetic signatures of huge numbers of different animals, even if we can’t see them. This free-floating DNA moves with ocean currents and can be sequenced to identify species ranging from copepods to dolphins, allowing researchers to track who is participating in the migration even when organisms are too small, fragile, or fast for traditional nets.

All of this plays out each day and night off our coast, a vast symphony of animal movement and deadly combat that, until recently, was not only poorly understood but largely invisible to science. And it’s all happening right off our shores