Lobster is delicious. Let’s just get that out of the way. Yes, I’m sure there are some who either don’t enjoy the taste of this prolific crustacean, or who are allergic, but for my part, lobster (with a small vial of melted butter) is ambrosia from the sea.

But beyond its place on the plate, the California spiny lobster plays a vital ecological role: hunting sea urchins, hiding in rocky reefs, and helping to keep kelp forests in balance. Its value extends far beyond what it fetches at market. But beneath the surface, particularly around the Channel Islands lurks a growing problem that doesn’t just threaten lobsters. It threatens the entire marine ecosystem: ghost traps.

In Southern California, lobster fishing is both a cultural tradition and a thriving industry, worth an estimated $44 million annually to California’s economy from commercial landings as well as recreational fishing, tourism, and seafood markets.

In late April, I traveled to the Channel Islands with my colleague Tod Mesirow to see the problem of ghost lobster traps firsthand. We were aboard the Spectre dive ship and pulled out of Ventura Harbor on an overcast morning, the sky a uniform gray that blurred the line between sea and cloud. The swell was gentle, but the air carried a sense of anticipati on. We were invited by the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory, which is conducting research and outreach in the area. Our visit took us to Anacapa and Santa Cruz Islands, where I would be diving to observe the traps littering the sea floor. Tod, meanwhile, remained topside, capturing footage and speaking with marine scientists. Even before entering the water, we could see the toll: frayed lines tangled in kelp, buoys adrift, and entire areas where dive teams had marked clusters of lost gear.

Ghost traps are lobster pots that have been lost or abandoned at sea. Made of durable metal mesh and often outfitted with bait containers and strong ropes, these traps are built to last. And they do. For years. Sometimes decades. The problem is, even when their human operators are long gone, these traps keep fishing.

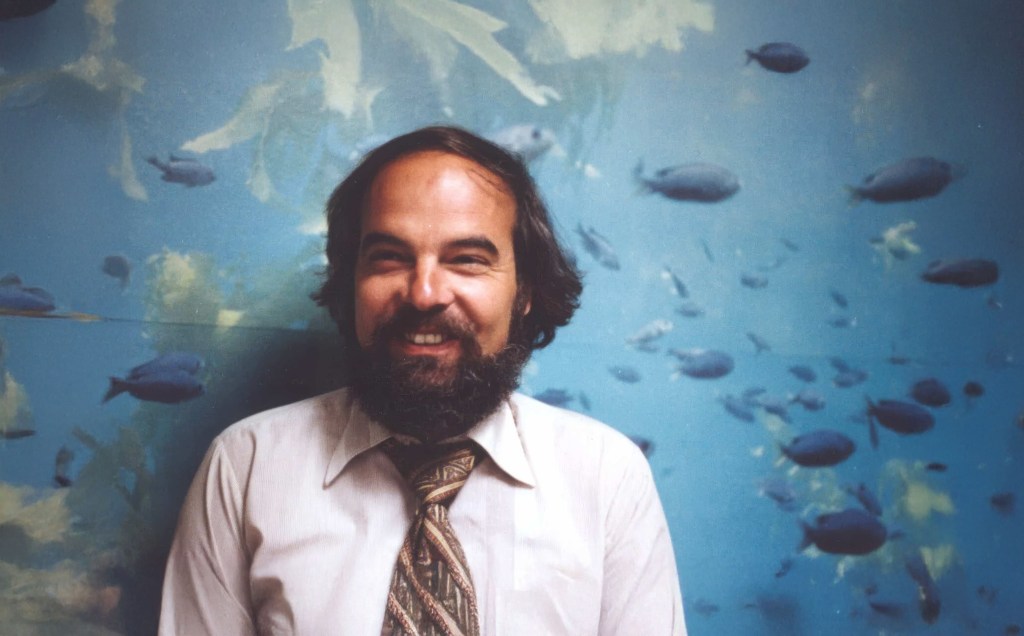

“It’s not uncommon to find multiple animals dead inside a single trap,” said Douglas McCauley, a marine science professor at UC Santa Barbara and director of the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory who was onboard with us and leading the project. “It’s heartbreaking. These traps are still doing exactly what they were built to do, just without anyone coming back to check them.”

Around the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary, where fishing pressure is high and waters can be rough, thousands of traps are lost every season. Currents, storms, or boat propellers can sever buoys from their lines, leaving the traps invisible and unrecoverable. Yet they keep doing what they were designed to do: lure lobsters and other sea creatures inside, where they die and become bait for the next unfortunate animal. It’s a vicious cycle known as “ghost fishing.”

“They call them ghost traps because, like a ghost sailing ship, they keep doing their thing. They keep fishing.” said McCauley.

Statewide, the numbers are staggering. Approximately 6,500 traps are reported lost off the California coast each fishing season, according to The California Department of Fish and Wildlife. The folks at the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory said as many as 6,000 may lie off the coast of the Channel Islands alone. Ocean Divers removing marine debris have found traps stacked three and four high in underwater ravines—rusting, tangled, but still deadly. These ghost traps don’t just catch lobsters; they also trap protected species like sheephead, cabezon, octopuses, and even the occasional sea turtle or diving seabird.

Nowhere is this more evident than around the Channel Islands. These rugged islands are home to some of California’s richest kelp forests and underwater canyons. The islands and their surrounding waters are home to over 2,000 plant and animal species, with 145 of them being unique to the islands and found nowhere else on Earth. In fact, the Channel Islands are often referred to as North America’s Galapagos for the immense diversity of species here.

The islands are also the site of the state’s most productive spiny lobster fisheries. Every fall, hundreds of commercial and recreational fishers flood the area, setting thousands of traps in a race to catch California spiny lobsters (Panulirus interruptus). But rough swells and heavy gear mean traps go missing. Boats sometimes cut the lines of traps, making them near impossible to retrieve from the surface. And because this region is a patchwork of state waters, federal waters, and marine protected areas (MPAs), cleanup and regulation are anything but straightforward.

The traps are often difficult to locate, partly because of their remote placement and the notoriously rough waters around the Channel Islands. But the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory has a powerful asset: side scan sonar. From the ship, they can scan and map the seafloor, where the ghost traps often appear as dark, rectangular shapes against the sand. Once spotted, the team uses GPS to log their exact location.

“It’s creates a picture made of sound on the seafloor and you see these large lego blocks staring at you in bright yellow on the screen and those are your lobster traps,” sayd McCauley. “There’s nothing else except a ghost trap that looks like that.”

Plunging into the frigid waters off Santa Cruz Island was a jolt to the system. Visibility was limited, just 10 to 15 feet, but I followed two scientists from the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory down to a depth of 45 feet. Their task: to attach a rope to the trap so it could be hauled up by the boat’s winch.

The water was thick with suspended particles, the light dimming quickly as we dropped lower. My 7mm wetsuit was just barely enough to stave off the cold. On the seafloor, the ghost trap emerged, a large rectangular cage resting dark and ominous in the sand. And it was teeming with life. Fish darted around its edges, lobsters clambered along the frame, and inside, several animals moved about, trapped and slowly dying. It was easy to see how a single trap could wreak quiet havoc for years.

California law technically requires all lobster traps to include biodegradable “escape panels” with zinc hinges that degrade over time, eventually allowing trapped animals to escape. But enforcement is tricky, and the panels don’t always work as intended. In practice, many traps, especially older or illegally modified ones, keep fishing long after they should have stopped. That’s what we were out here to find.

Complicating matters is the fact that once a trap goes missing, there’s no easy way to retrieve it. Fishers are not legally allowed to touch traps that aren’t theirs, even if they’re obviously abandoned. And while a few small nonprofits and volunteer dive teams conduct periodic ghost gear removal missions, they can’t keep pace with the scale of the problem.

“At this fishery, we can’t get them all,” says McCauley. “But by going through and getting some species out and getting them back in the water, we’re making a difference. But in the process, we’re coming up with new ideas, new technologies, new research methods, which we think could play a role in and actually stopping this problem in the first instance.”

Back topside, the recovery team aboard the Spectre used a powerful hydraulic winch to haul the trap onto the deck. After climbing out of the cold water, still shivering, I joined the others to get a closer look. The trap was heavy and foul-smelling, but what stood out most was what was inside: lobsters, maybe ten or more. Some had perished, but many were alive and thrashed their tails when lifted by the scientists. Females could be identified by their broader, flatter tail fins—adapted to hold eggs. The team carefully measured each one before tossing them back into the sea, the lobsters flipping backward through the air and disappearing into the depths.

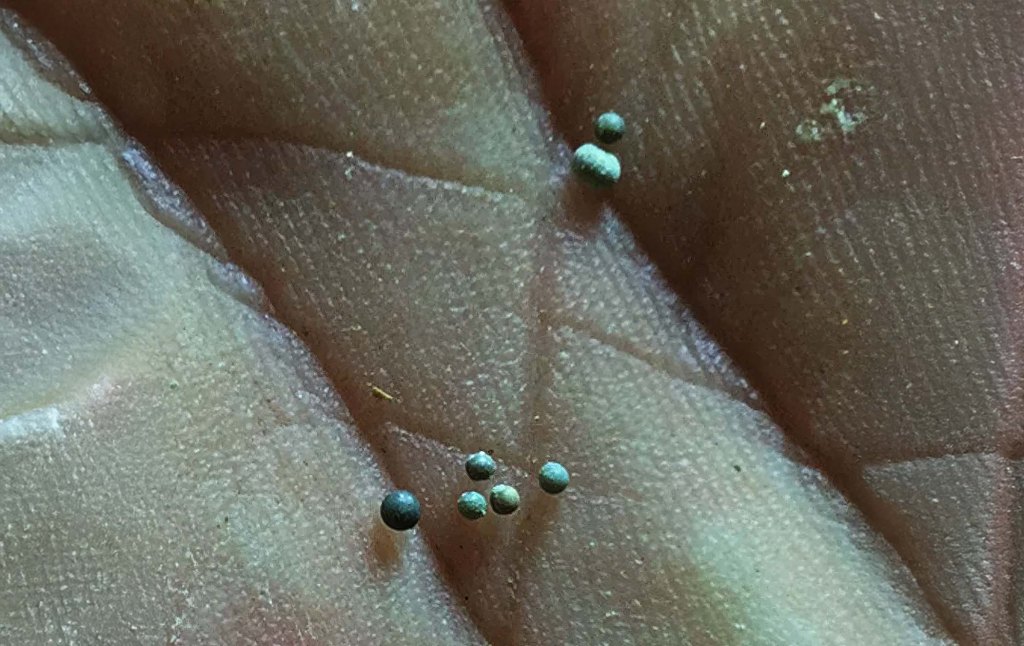

There were other animals, too. Large, rounded crabs known as Sheep crabs, common to these waters, scuttled at the bottom of the trap. Sea snails were clustered along the mesh, and in one cage, there were dozens of them, clinging and crawling with slow purpose. Even baby octopuses made appearances, slithering out onto the deck like confused aliens. I picked one up gently, marveling at its strange, intelligent eyes and soft, shifting forms, before tossing it back into the sea in hopes it would have another chance at life.

By then, the day had brightened and the sun had come out, easing the chill that lingered after the dive. The traps would be taken back to Ventura, where they’d likely be documented and disposed of. But this day wasn’t just about saving individual animals or pulling traps off the seafloor—it was about data. The Benioff team wants to understand just how big of a problem ghost traps really are. It’s not just about the number of traps lost each season, but the broader ecological toll: how many animals get caught, how many die, and how these traps alter the underwater food web. Every recovered trap adds a piece to the puzzle. This trip was about science as much as rescue.

State agencies, including the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW), have started pilot programs aimed at tackling ghost gear. In 2023, CDFW launched a limited recovery permit program that allows fishers to collect derelict traps at the end of the season, provided they notify the state. But participation is voluntary and poorly funded.

Elsewhere, states like Maine and Florida have created large-scale, state-funded programs to identify and remove ghost traps, often employing fishers in the off-season. California, despite having the nation’s fourth-largest lobster fishery, has yet to make a similar investment.

Some solutions are already within reach. Mandating GPS-equipped buoys for commercial traps could help track and retrieve gear before it’s lost. More robust escape hatch designs, made from materials that dissolve in weeks rather than months, would shorten the lifespan of a lost trap. And expanding retrieval programs with funding from fishing license fees or federal grants could make a big dent in ghost gear accumulation.

But even more powerful than regulation may be public awareness. Ghost traps are out of sight, but their damage is far from invisible. Every trap left behind in the Channel Islands’ waters becomes another threat to biodiversity, another source of plastic and metal waste, and another reminder that marine stewardship doesn’t stop when the fishing season ends.

Key to the whole effort is data:

“Every one of the animals that we put back in the water today, we’ll be taking a measure,” says McCauley. “After a little bit of crunching in the lab, we’ll be able to say, oh, actually, you know, every single trap undercuts the fishery by x percent for every single year that we don’t solve the problem.”

As we headed back toward Ventura, Tod and I talked with Douglas McCauley and Project Scientist Neil Nathan from the Benioff Ocean Science Laboratory. The team had collected a total of 13 traps that day alone, and 34 over the several days they’d been out. There was a sense of satisfaction on board, quiet but real. Each trap removed was a small win for the ecosystem, a little less pressure on an already strained marine environment.

“I would call today an incredible success, ” said Neil Nathan. “Feeling great about the number of traps we collected.”

California has long been a leader in ocean conservation. If it wants to stay that way, it needs to take ghost fishing seriously, not just around the Channel Islands, but up and down the coast. After all, we owe it to the lobsters, yes, but also to the underwater forests, reef communities, and countless species whose lives are tangled in the nets we leave behind.