Having spent much of my youth in Newport Beach, my life was shaped by the ocean. I spent countless days in the surf, bodyboarding, bodysurfing, or playing volleyball on the sand with friends. When a southern storm rolled through, we’d rush to Big Corona and throw ourselves into the heavy swells, often getting slammed hard and learning deep respect for the ocean, a respect that I still harbor today. Sometimes the waves were so large they were genuinely terrifying, the kind of surf that would have made my mother gasp, had this not been an era when parents rarely knew what their kids were doing from dawn to dusk. That freedom, especially in Southern California, made the ocean feel like both a playground and a proving ground.

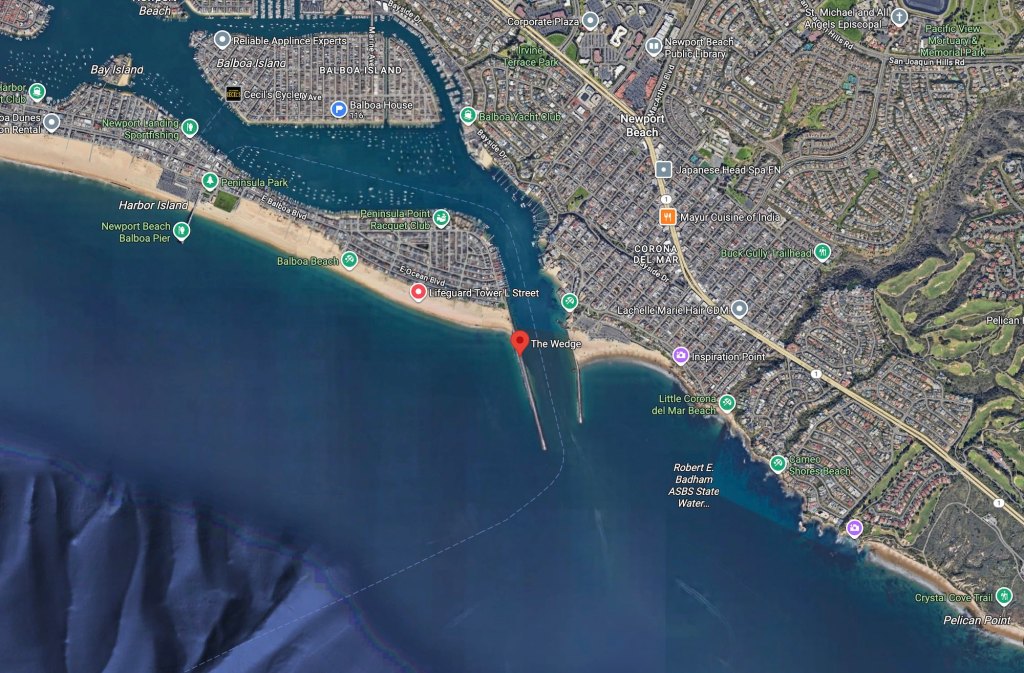

Across the channel at the Newport jetty was where the action was most intense. The surf was bigger, louder. We sat on the sand and held back, watching the brave and sometimes the foolish throw themselves into the water. That place, then and now, is called the Wedge.

There is something unforgettable about the Wedge and the way its waves crash with such raw force. Sometimes they detonate just offshore, sending water skyrocketing into the air; other times they slam thunderously against the sand, eliciting groans and whoops from bystanders. The waves behave strangely at the Wedge, smashing into one another, often combining their force, and creating moments of exquisite chaos.

These colliding waves are what make the place both spectacular and dangerous, the result of a unique mix of physics and geology that exists almost nowhere else on earth. That combination has made it, to this day, one of the world’s most famous surf and bodysurfing spots. If you want a glimpse of what I mean, just search YouTube, where the insanity speaks for itself. This compilation is from earlier this year.

And of course, who could forget this one surfer’s unique brand of SoCal eloquence.

So how did the Wedge turn into one of the most famous and dangerous surf spots? The truth is, it’s mostly the result of human engineering.

The Wedge’s origin story begins in the 1930s, when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers extended Newport Harbor’s West Jetty to protect the harbor mouth from sand buildup and currents. What no one anticipated was that this angled wall of rock would create a perfect mirror for waves arriving from the south and southwest. Instead of dispersing, these waves slam into the jetty and reflect diagonally back toward the shore. The reflected energy doesn’t dissipate, it collides with the next incoming wave. When the two wave crests line up in phase, their energies combine, and the result is a much steeper, taller, and more powerful wave. In physics this is known as constructive interference: two sets of energy stacking into a single, towering peak.

This wave-doubling effect only works under specific conditions. Long-period south swells, often generated by hurricanes off Mexico or storms deep in the South Pacific, line up nearly parallel to the jetty. Their orientation means maximum contact and reflection. Surfers and bodysurfers describe the result as a pyramid-shaped breaker, or wedge, rising steeply before collapsing with extraordinary force. On the biggest days, these waves can reach 20 to 30 feet, twice the size of surrounding surf.

Geology and geography make the situation even more dramatic. The seafloor near The Wedge slopes upward very steeply into a narrow strip of beach. Instead of allowing waves to break gradually, the bathymetry forces them to jack up suddenly, creating a thick lip that pitches forward into shallow water. It’s called a shorebreak, and man, they can be dangerous. More on that in a moment.

Unlike classic point breaks such as Malibu, where waves peel cleanly along a gradual reef, The Wedge produces brutal closeouts: vertical walls of water that crash all at once, leaving no escape route.

It actually can get worse. After each wave explodes on the beach, the backwash races seaward, colliding with the next incoming swell and adding more turbulence. Surfers call it chaos; lifeguards call it dangerous, even life-threatening. Spinal injuries, broken bones, and concussions are common at The Wedge. By 2013, the Encyclopedia of Surfing estimated that the Wedge had claimed eight lives, left 35 people paralyzed, and sent thousands more to the hospital with broken bones, dislocations, and other trauma—making it the most injury-prone wave break in the world. A 2020 epidemiological survey places The Wedge among the most lethal surf breaks globally (alongside Pipeline and Teahupo’o), largely due to head-first “over the falls” impacts on the shallow sea floor.

Interesting fact: Long before the Wedge was built, the waves pounding that corner of the Newport Beach jetty were already fierce. In 1926, Hollywood icon John Wayne (then still Marion Morrison) tried bodysurfing there while he was a USC football player. He was slammed into the sand, shattering his shoulder and ending his athletic scholarship. The accident closed the door on his football career but opened the one that led him to Hollywood stardom.

Oceanographers have studied the physics behind the Wedge’s unique surfbreak in broader terms. Research into wave reflection and interference confirms what locals have known for decades: man-made structures like jetties can redirect swell energy in ways that amplify, rather than reduce, wave height. Studies on steep nearshore bathymetry show how sudden shoaling increases the violence of breaking waves. The Wedge combines both effects in one location, making it a rare and extreme case study in coastal dynamics. In other words, yes, it’s gnarly.

Of course, with all that danger comes spectacle, and when the Wedge is firing, it’s not unusual for hundreds of spectators to line the sand and jetty to watch. In August 2025, the California Coastal Commission approved plans for a 200-foot ADA-compliant concrete pathway and a 10-foot-wide viewing pad along the northern jetty, designed to make the experience safer and more inclusive. The project will provide better access for people using wheelchairs, walkers, and strollers, while also giving life guards and first responders improved vantage points when the surf turns chaotic.

I still get to the Wedge on occasion to watch the carnage. And while in my younger years, I might have ventured out to catch a wave or two if the conditions were relatively mellow, today, I prefer the view from shore, leaving the powerful surf to the younger bodysurfers hungry for a rush.