If there’s one thing our increasingly digital world has pushed me toward, it’s a desire to reconnect with the natural one. At a moment when AI, deepfakes, and synthetic media blur the line between real and artificial, I find myself drawn more strongly to things that are undeniably, stubbornly real. So I spend a lot of time turning away from screens and paying closer attention to the world around me, searching for things in nature that are touchable, tangible, and timeless.

It turns out California is full of those opportunities, and I want to call your attention to just one: a plant.

The New York Times ran a fascinating piece recently about a type of plant that is both ancient and highly unusual, and one that I suspect most people know very little about: cycads. Many cycads resemble palm trees at first glance, but that’s misleading. Cycads are only distantly related to palms, belonging instead to one of the oldest surviving lineages of seed plants on Earth, the gymnosperms. Palms, by contrast, are angiosperms, or flowering plants, making them evolutionary newcomers compared to cycads, which were already thriving long before flowers existed at all. In fact, cycads and palms diverged from a common ancestor approximately 300 to 350 million years ago. Their apparent similarity in form is not a sign of close kinship but a classic case of convergent evolution, in which unrelated organisms independently arrived at a similar form because of adaptation in similar environments.

I have always found cycads really cool, in part because they are some of the closest living things we have to connect us to the era of the dinosaurs, and because they just look — and feel — incredibly bizarre compared to most other plants. And the Times piece made clear that we are still actively learning how they work, which I find fascinating.

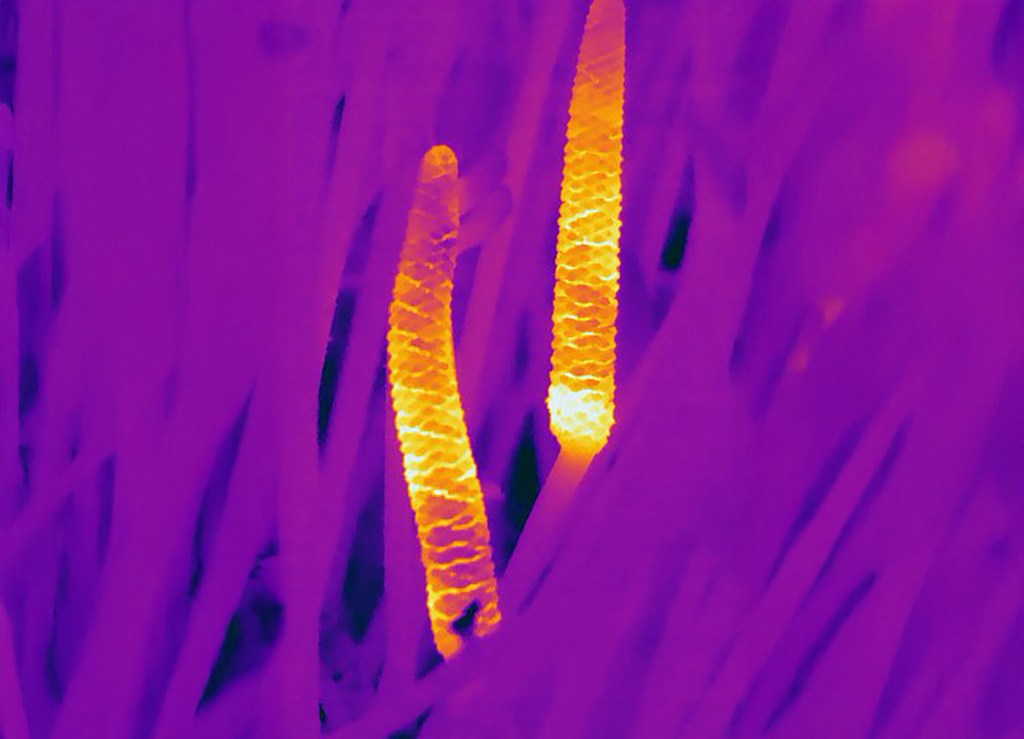

The Times piece explains that cycads attract insect pollinators not through color or flowers, but by heating their cones at dusk and emitting infrared radiation. The process is known as thermogenesis and its rare in plants. (It turns out the female Skunk Cabbage, for example, warms up to melt away snow in the winter.) Specialized beetles, equipped with infrared-sensing antennae, detect this warmth and are guided from male cones to female cones (more on this in a sec) in a precisely timed sequence that ensures pollination. The relationship is so ancient, stretching back hundreds of millions of years, that some researchers now suspect heat-based signaling may lie at the very foundation of pollination, long before flowers evolved petals, color, and scent. However, this is controversial.

Fascinating, right? That’s just the beginning.

My interest in cycads grew out of the many visits I have made to two major botanical gardens in Southern California that I return to again and again: Descanso Gardens and the Huntington. While The Huntington features a world-renowned, massive scientific collection of over 1,500 plants sprawling across a specialized hillside Cycad Walk, Descanso Gardens offers a boutique, immersive “Ancient Forest” experience that replicates a prehistoric Jurassic environment beneath a canopy of redwoods. Both are really excellent to walk through. And these collections, unlike most museum encounters you might encounter with ancient life (i.e. dinosaur bones), consist of live plants you can actually walk among and touch.

One of the most remarkable features of cycads is the toughness of their leaves. They are much stiffer and heavier than other plants. Almost plastic and fake. It turns out cycads invest in a thick, waxy cuticle that has some key benefits: it reduces water loss, reflects harsh sunlight, and protects them against insects and grazing animals. In other words, they are both survivors and a difficult meal, offering a key evolutionary advantage during a time when giant plant-eating dinosaurs roamed the Earth.

(That said, there is evidence that some dinosaurs actually did feed on cycads. There are telltale signs of cycad cellular material in dinosaur coprolites, or fossilized poop, but scientists don’t think it was common.)

And then there are the cones.

Cycad cones are among the strangest reproductive structures in the plant world. They are often massive, sometimes weighing many pounds, tightly packed, and so symmetrical they look almost engineered, as if they were 3D printed. They are also unusual because each individual cycad plant is strictly male or female, a condition known as dioecy. A male cycad will only ever produce pollen-bearing cones, while a female will only produce seed-bearing cones. Pines and firs, which are also gymnosperms, typically produce both male and female cones on the same plant. Cycads do not. There is no overlap between the sexes, no ability to self-fertilize, and no natural fallback mechanism if a partner is missing. (Cycads can be “bred” using off-shoots or pups, which is how many of the plants in these gardens came to be.)

That odd rigidity is on display at The Huntington in San Marino, which has one of the earth’s few specimens of Encephalartos woodii, often called “the loneliest plant in the world”. Only a single wild male was ever found, in South Africa in the late 1800s, and no female has ever been discovered (although scientists are using drones and AI to find one). There are a few other specimens alive today outside the Huntington, but they are all clones propagated from that one original plant. There’s a great Instagram from the Huntington on this.

So, the male cycad cones produce pollen and the female cycads make seeds. In several species of cycad, those seeds are big and glossy and plump and bright red or orange. They look temptingly like fruit, although remember that true fruits didn’t evolve until much later, with flowering plants. They do have a fleshy outer layer called a sarcotesta that looks and feels fruit-like, but it’s not. That’s weird.

In another bizarre twist, those seeds are loaded with potent toxins that are very dangerous to animals, including humans. They can damage the liver and the nervous system, and even kill. (So even though I urged you to touch the leaves, maybe don’t handle the seeds…or at least wash your hands afterwards, and certainly don’t try to cook and eat them.)

Why make a seed dressed in bright, attractive colors if it’s toxic? That question has long puzzled scientists. Bright colors usually signal an edible reward, but in cycads the fleshy outer layer of the seed, the sarcotesta, is not toxic and does contain nutrients. The toxins are concentrated deeper inside the seed, suggesting the sarcotesta may have served as a non-fruit mechanism for seed dispersal, encouraging animals to handle or partially consume the seed while the embryo itself remained protected.

Cycads are not indigenous to California. In nature, they are found almost entirely in tropical and subtropical regions, growing in parts of Africa, Australia, Asia, and the Americas, often in warm, stable landscapes that long predate California’s modern climate. That said, Southern California turns out to be an unusually good place to grow cycads. We have mild winters, dry summers, and a long growing season, which mimic the conditions in which cycads evolved across Africa, Australia, and parts of the Americas. That made the region attractive to collectors early on in the 20th century, when botanical gardens were expanding their missions from display to preservation.

“We are in a actually in a biodiversity hot spot here in California,” Sean C. Lahmeyer Associate Director, Botanical Collections, Conservation and Research at the Huntington told me. “Because of our climate in California we’re able to grow so many different types of plants. If you were to compare this garden to, say, one in England or at Kew, they have to grow things inside of greenhouses.”

At The Huntington, cycads arrived largely through early plant collecting and exchange. Henry Huntington’s gardeners were building a world-class botanical collection at the same time as explorers and botanists were (controversially) bringing rare plants back from around the globe. Over decades, the Huntington expanded its cycad holdings, recognizing both their horticultural appeal and their scientific importance. Today, it houses one of the most significant cycad collections anywhere, including that famous Encephalartos woodii.

Descanso Gardens’ story, meanwhile, is more personal and more recent. In 2014, local residents in La Canada Flintridge, Katia and Frederick Elsea donated their private cycad collection, more than 180 plants representing dozens of species, to the garden. Many were rare, endangered, or extinct in the wild. Descanso said yes, of course, and built the Ancient Forest around them, and suddenly one of the most important cycad collections in the country was open to the public in La Cañada Flintridge.

Cycads are not all rare. You may even notice certain common specimens growing in people’s yards around California. But precisely because they are so ancient and so different from most plants we’re used to, I’d urge you to see them in person at places like Descanso Gardens and The Huntington. Touch the leaves. Study the symmetry. Marvel at the massive cones. (Just don’t put anything in your mouth.) Take a moment to consider just how unusual these plants are. And if you feel the need to pull out your phone to learn more, go ahead, but then put it away and spend a little time with the plants themselves.

Discover more from California Curated

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.