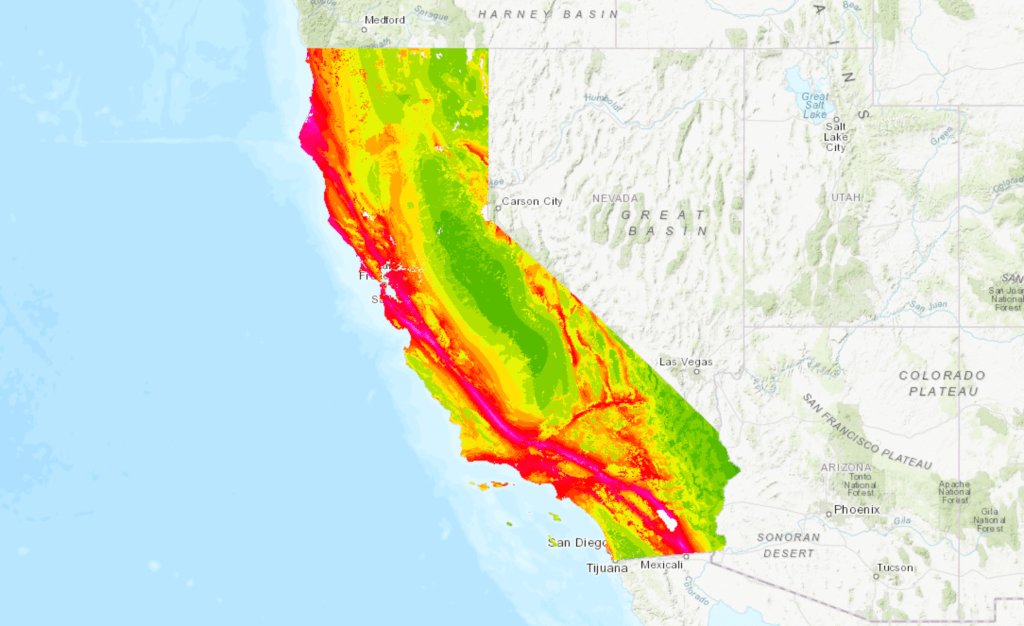

We all know California is known for earthquakes. AND most people probably know there’s a reason for that: California lies along the Pacific Ring of Fire, and it also sits at the boundary between the Pacific and North American tectonic plates, creating the San Andreas Fault and making it especially prone to seismic shaking. Even if you’ve lived here for just a short while, the chances are you’ve felt a tremble or two.

Of course, the biggest earthquake most people are aware of in California was the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco, which shook the city hard and led to a massive, all-consuming fire that together destroyed more than 28,000 buildings, killed an estimated 3,000 people, left roughly a quarter million residents homeless, and reshaped the city’s development and building practices for decades afterward. (Here’s a story about one particularly important building). One of my favorite books on the subject is Simon Winchester’s Crack at the Edge of the World, which is filled with wonderful facts and stories about California’s precarious geology and what happened that day in San Francisco.

More recent events continue to underscore the ever-present threat of significant temblors. In December 2024, a 7.0-magnitude earthquake struck off the coast near Eureka, prompting tsunami warnings and evacuations. More recently, in March 2025, the Bay Area experienced a series of minor tremors along the Hayward Fault. While these quakes caused minimal damage, there is always the looming threat of ‘The Big One’, a potentially catastrophic earthquake expected along the San Andreas Fault, well, any day now . Scientists warn that the southern section, overdue for a major rupture, could trigger widespread destruction, with estimates suggesting a magnitude 7.8 event could result in “significant casualties and economic losses”.

(Photo: Paul Sakuma/AP)

But what about that number, 7.8? Where does it actually come from, and what does it mean?

When we talk about measuring earthquakes: their size, their energy, their destructive potential, most of us still instinctively think of the Richter scale. It’s now shorthand for seismic strength, although, ironically, scientists today rely on other, more modern magnitude systems. We’ll get to that shortly. But the Richter scale remains one of the most influential ideas in the history of earthquake science.

The story of how it came to exist starts in a lab at a world-renowned scientific institution in Pasadena: the California Institute of Technology (CalTech). It begins with a physicist named Charles Richter.

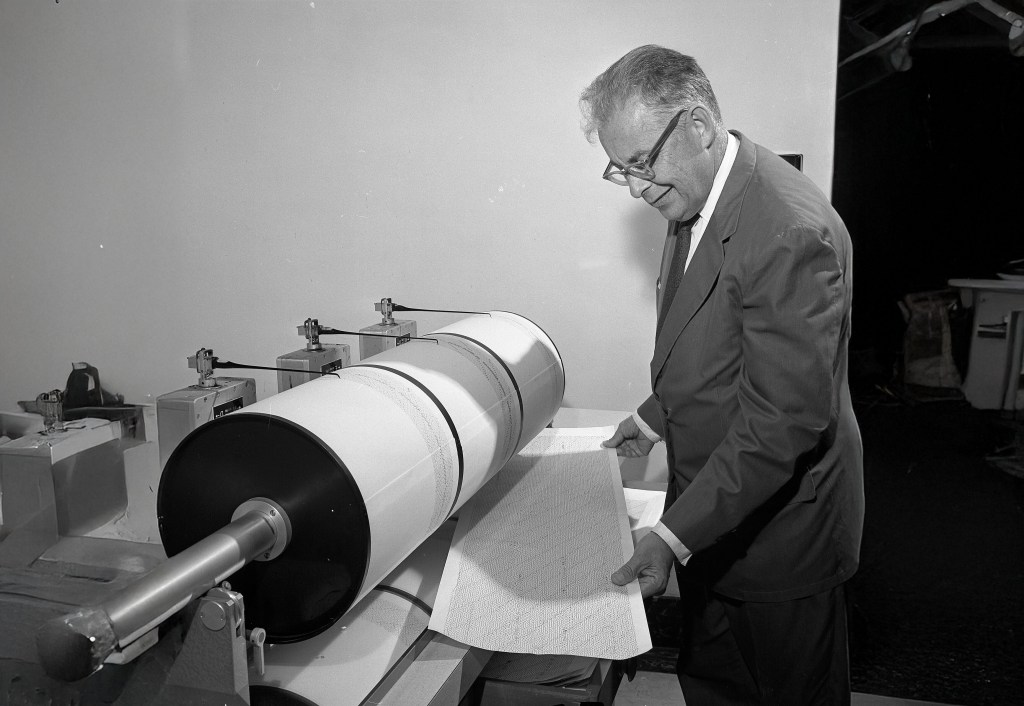

In 1935, working with German-born seismologist Beno Gutenberg, Richter laid the groundwork for modern earthquake study and quantification. Their breakthrough work helped transform vague and subjective observations into precise, quantifiable data. Scientists could now better assess seismic risk and ultimately help protect lives and infrastructure. So the effort not only changed how we understand earthquakes, it laid the foundation for future advances in seismic prediction and preparedness.

(Credit: Wikipedia and Gil Cooper, Los Angeles Times)

At the time, existing intensity-based earthquake measurements relied on subjective observations and the so-called the Mercalli Intensity Scale. That means that an earthquake’s severity was determined by visible damage and how people felt them. So, for example, a small earthquake near a city might appear “stronger” than a larger earthquake in a remote area simply because it was felt by more people and caused more visible damage. For example, the 1857 Fort Tejon earthquake, estimated around magnitude 7.9, ruptured hundreds of miles of the San Andreas Fault, but because it struck a sparsely populated stretch of desert and ranch land, it caused relatively little recorded damage and few deaths.

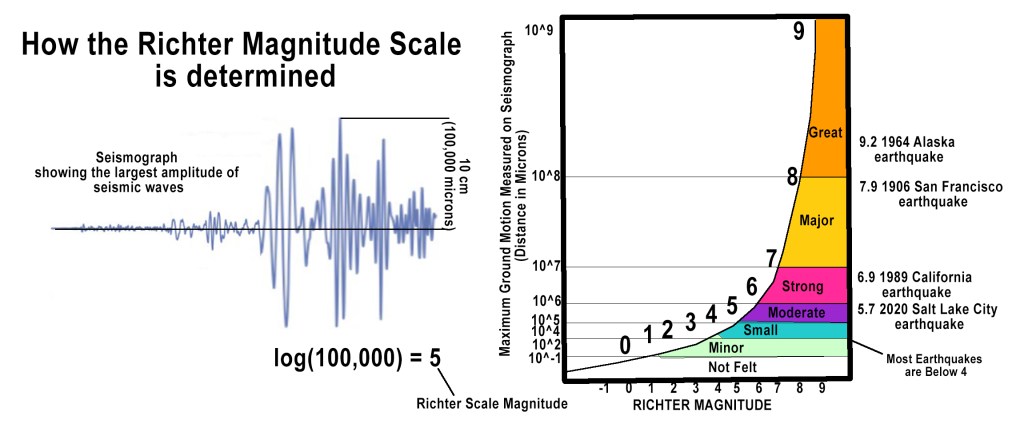

Like any good scientist, Richter wanted to create a precise, instrumental method to measure earthquake magnitude. He and Gutenberg designed the Richter scale by studying seismic wave amplitudes recorded on Wood-Anderson torsion seismometers, an instrument developed in the 1920s to detect horizontal ground movement. Using a base-10 logarithmic function, they developed a system where each whole number increase represented a tenfold increase in amplitude and roughly 31 times more energy release. This allowed them to compress a wide range of earthquake sizes into a manageable, readable scale. So, for example, a magnitude 6 quake shakes the ground 10× more than a magnitude 5. Also, a magnitude 7 quake releases about 1,000× more energy than a magnitude 5 (i.e. 31.6 × 31.6 ≈ 1,000).

The innovation allowed scientists to compare earthquakes across different locations and time periods, significantly improving seismic measurement and research.

Once the Richter scale came into being, it not only changed how scientists described earthquakes, it changed how we all thought about them. Earthquakes were no longer defined only by damage or casualties, but by a single, authoritative number. And so by the 1960s and 1970s, “the Richter scale” had become standard language in news reports and scientific writing. Even today, long after researchers have moved to newer magnitude systems, you still occasionally see it in news reports.

The Richter Scale, and Richter himself, became so well known on campus, that one of Caltech’s great comic writers and performers, J. Kent Clark, actually wrote a song about them:

“When the first shock hit the seismo, everything worked fine. It measured:

One, two, on the Richter scale, a shabby little shiver.

One, two, on the Richter scale, a queasy little quiver.

Waves brushed the seismograph as if a fly had flicked her.

One, two, on the Richter scale, it hardly woke up Richter.”

Alas, Richter, according to Clark, was so “morbidly shy” that he never showed up to any of the performances. At first, he didn’t like the song, reportedly calling it an “insult to science”, but later in life he came to appreciate its good humor. There’s a YouTube reading of the song here.

Unfortunately for Richter, over time it became clear that the Richter scale had a fundamental flaw: it couldn’t measure the largest earthquakes accurately. Because it relies on seismic wave amplitude, very powerful quakes tend to “saturate” on the scale, making different events appear similar in size.

Since the 70s scientists have come up with another way to measure earthquakes called the Moment Magnitude Scale. Developed by Hiroo Kanamori and Thomas Hanks the Moment Magnitude Scale calculates how much energy an earthquake actually releases by examining the size of the fault that slipped, how far it moved, and the physical properties of the surrounding rock. The method works reliably for both small tremors and the planet’s largest earthquakes, which the original Richter scale struggled to do.

Of course, neither the Richter scale nor the Moment Magnitude Scale have done much to help us actually predict earthquakes. That remains an elusive dream. That said, ShakeAlert, the state’s early-warning system, doesn’t predict quakes, but it can detect them as they begin and send alerts before the worst shaking arrives. Those seconds can be enough to drop to the ground, slow trains, or shut down sensitive systems. The system has also had misfires and missed alerts, so we’re not there yet.

Dr. Lucy Jones, who helped champion early earthquake warning in California, has said that ShakeAlert usually works exactly as intended. It is “tuned” to avoid sending alerts for minor shaking, because otherwise people would be getting notifications all the time, creating a kind of Chicken Little problem where warnings start to lose their impact.

According to experts involved with the system, ShakeAlert is designed to send alerts for earthquakes in L.A. County with a magnitude of at least 5.0, or for quakes anywhere that are strong enough to produce “light” shaking in the Los Angeles area. But according to news reports, that sometimes leaves people feeling disappointed or confused. During the 2019 Ridgecrest quakes, for example, Los Angeles didn’t receive a public alert because the shaking there was below the warning threshold, although many people felt it. Jones has said the real challenge isn’t just the technology, but making sure alerts are communicated in a way people understand and trust.

If there is ever a “Big One,” and scientists say it’s a matter of time, we can only hope we’ll get even a small amount of early notice.

Discover more from California Curated

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.