It’s time for California to put people back in the deep. A human-occupied submersible belongs in California waters, and we’ve waited long enough.

For decades, the state had a strong human-occupied submersible presence, from Navy test craft in San Diego to long-serving civilian science HOVs like the Delta. Those vehicles have been retired or relocated, leaving the West Coast without a single home-based, active human-occupied research submersible (I am not counting OceanGate’s Titan sub for numerous reasons, like the fact it was based in Seattle, but foremost is it was not “classed,” nor was it created for scientific use). Restoring that capability would not only honor California’s legacy of ocean exploration but also put the state back at the forefront of direct human observation in the deep sea. The time has come.

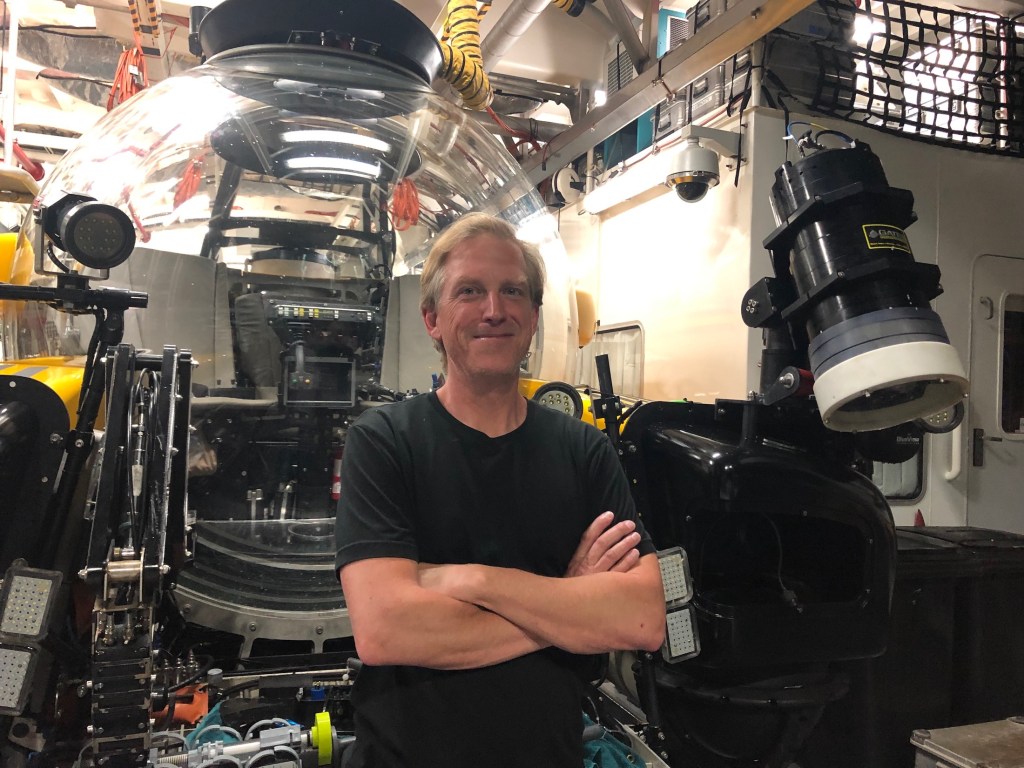

Side note: I’ve had the rare privilege of diving beneath the waves in a submersible three times in three different subs, including one descent to more than 2,000 feet with scientists from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Without exaggeration, it stands among the greatest experiences of my life.

The United States once had a small fleet of working research HOVs. Today it has essentially one deep-diving scientific HOV in regular service: Alvin, operated by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) for the National Deep Submergence Facility. Alvin is magnificent, now upgraded to reach 6,500 meters, but it is based on the Atlantic (in Massachusetts) and scheduled years in advance at immense cost.

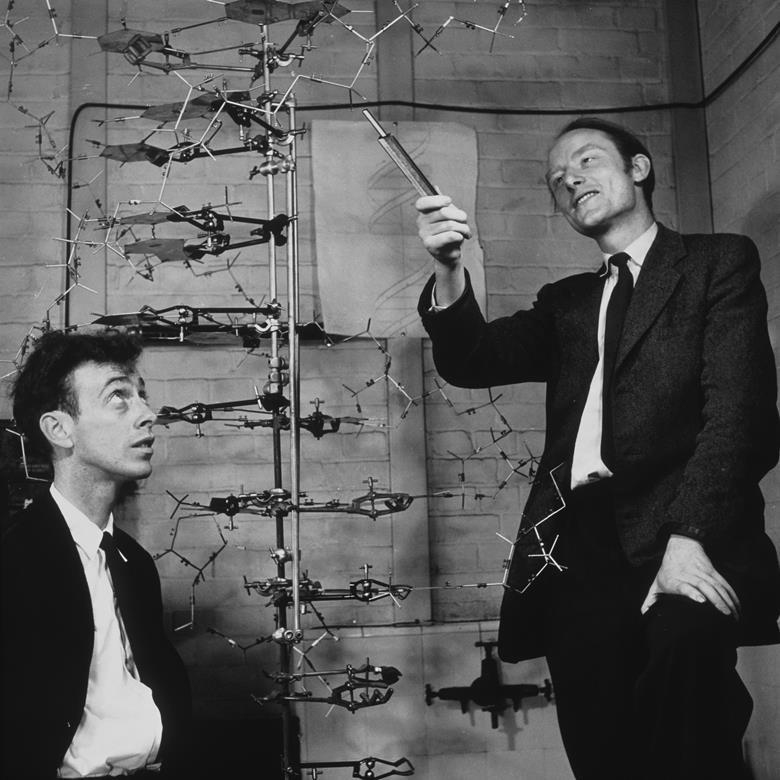

It helps to remember how we got here. The Navy placed Alvin in service in 1964, a Cold War investment that later became a pillar of basic research, investigating hydrothermal vents, shipwrecks and underwater volcanoes, among many, many other accomplishments. Over six decades of safe operations, Alvin has logged thousands of dives and undergone multiple retrofits, each expanding its depth range. Now rated to 6,500 meters, it can reach 98 percent of the ocean floor. WHOI’s partnership model with the Navy and universities shows exactly how public investment and science can reinforce each other. But Alvin is based on the East Coast: all that capability, history, and expertise is thousands of miles away. California needs its own Alvin. Or something even better…and perhaps cheaper. Though by cheaper I do not mean less safe.

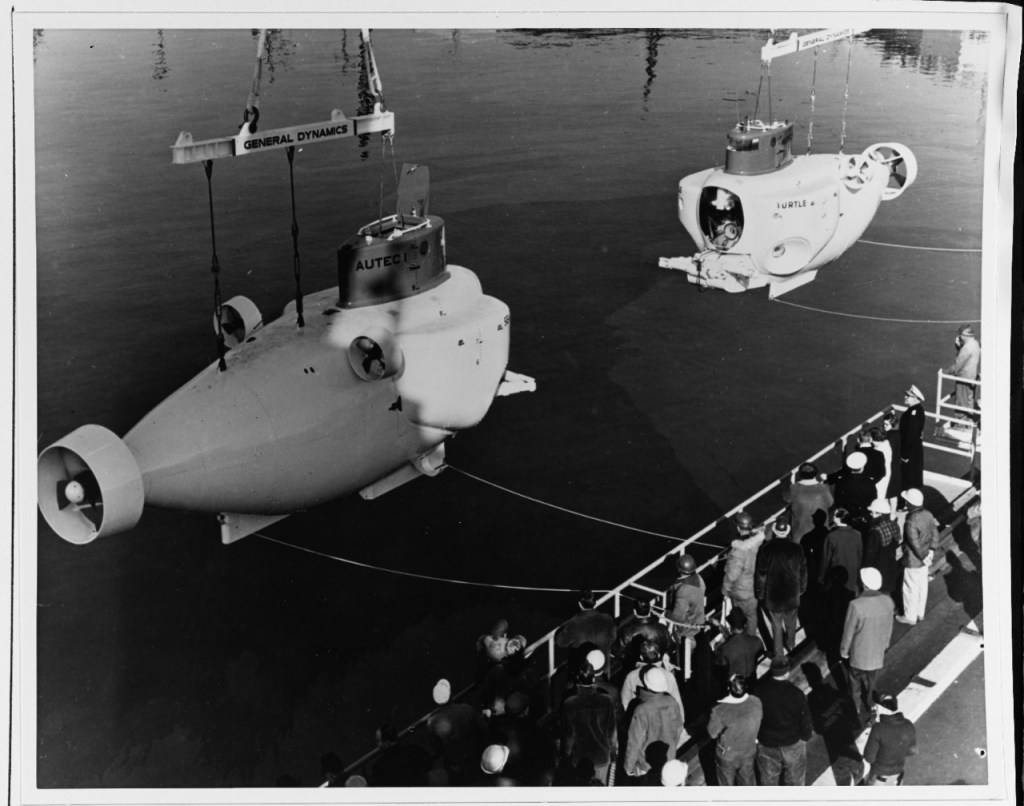

For a time, California actually had multiple HOVs. The Navy fielded sister craft to Alvin, including Turtle and Sea Cliff. Both Turtle and Sea Cliff spent their careers with Submarine Development Group ONE in San Diego. Turtle was retired in the late 1990s, and Sea Cliff, launched in 1968 and later upgraded for greater depths, also left service by the end of that decade, ending the Navy’s home-ported HOV presence on the West Coast.

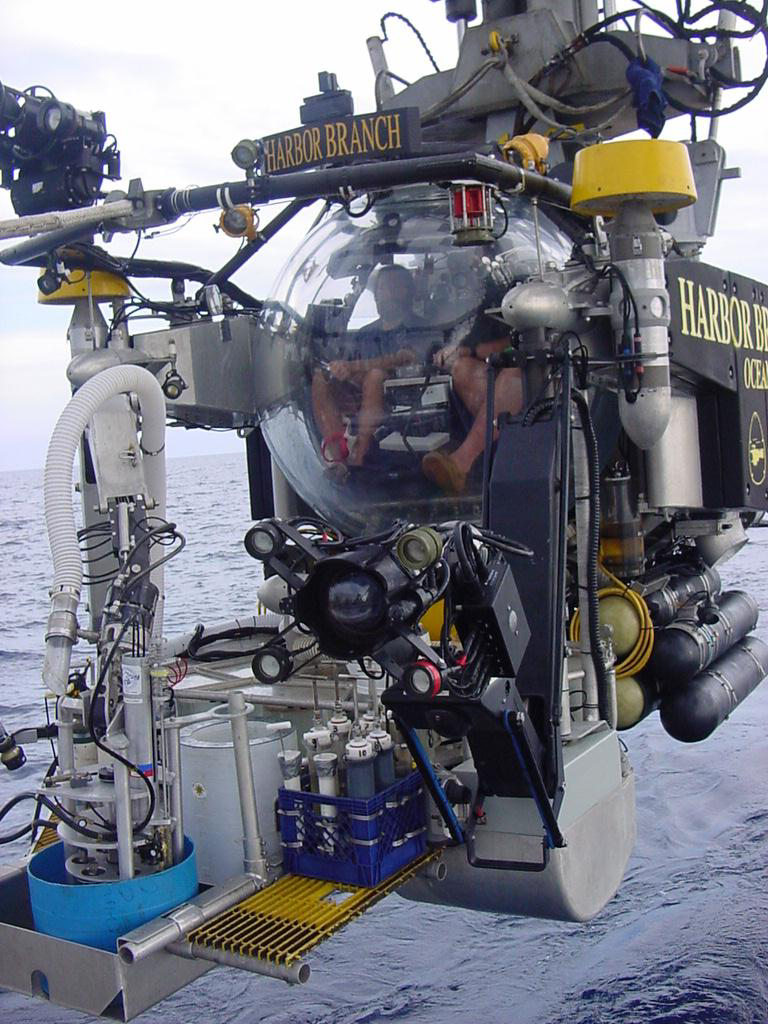

On the Atlantic side, Harbor Branch’s two Johnson Sea Link HOVs supported science and search-and-recovery work for decades before the program ended in 2011 due to funding constraints and shifting research priorities. I’ve interviewed renowned marine biologist Edith Widder several times, and she often speaks about how pivotal her dives in the Johnson Sea Link submersibles were to her career studying animal bioluminescence.

“Submersibles are essential for exploring the planet’s largest and least understood habitat, ” Widder told me. “A human-occupied, untethered submersible offers an unmatched window into ocean life, far surpassing what remotely operated vehicles can provide. ROVs, with their noisy thrusters and blazing lights, often scare away marine animals, and even the most advanced cameras still can’t match the sensitivity of the fully dark-adapted human eye for observing bioluminescence.”

In the central Pacific, the University of Hawaiʻi’s HURL operated Pisces IV and V for much of the 2000s and 2010s, then suspended operations amid funding and ship transitions. Through attrition and budget choices, the working U.S. fleet shrank from a handful to essentially one deep-diving research HOV today.

Manned submersibles are costly to build and operate, and they demand specialized crews, maintenance, and support ships or platforms. It’s easy to list reasons why California shouldn’t invest in a new generation of human-occupied subs. But that mindset has kept us out of the deep for far too long. It’s time to turn the conversation around and recognize why having one here would be a transformative asset for science, education, and exploration.

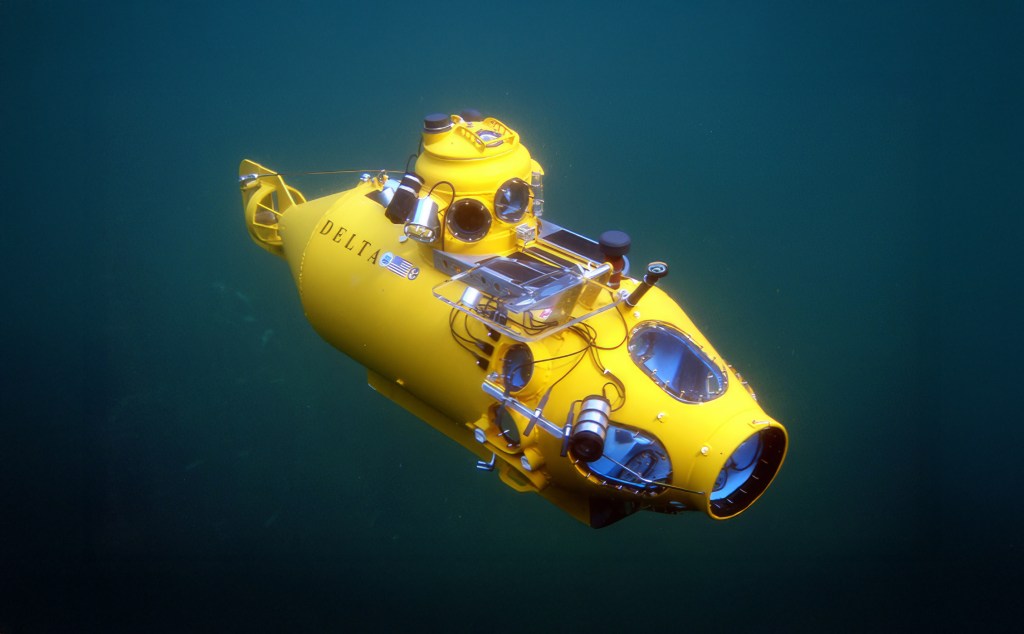

California’s own human-occupied sub legacy is short, but notable. In addition to the Navy submersibles noted above, the Delta submersible, a compact, ABS-class HOV rated to about 1,200 feet, operated from Ventura and later Moss Landing, supporting dozens of fishery and habitat studies from the Southern California Bight to central California. Built by Delta Oceanographics in Torrance, Delta dives in the mid-1990s produced baseline data that still underpin rockfish management, MPA assessments, and predictive habitat maps. The sub’s ability to place scientists directly on the seafloor allowed for nuanced observations of species behavior, habitat complexity, and human impacts that remote tools often miss. Many of these datasets remain among the most detailed visual records of California’s deeper reef ecosystems.

In the late 1990s, the program shifted north to Moss Landing, where it was operated in partnership with the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) and other institutions. At the time, MBARI was still in the early years of exploring human-occupied vehicles, like Bruce Robison’s experience piloting the Deep Rover HOV in Monterey Canyon in 1985. To many at MBARI, human occupancy in submersibles began to seem more like a luxury than a necessity. If the goal was to maximize scientific output and engineering innovation, remotely operated vehicles offered longer bottom times, greater payload capacity, and fewer safety constraints. That realization drove MBARI to invest heavily in ROV technology, setting the stage for a long-term move away from human-occupied systems.

Which leads us to the present moment: California’s spectacular coast faces mounting environmental threats, just as public interest in ocean science wanes. And yet, we have no human-occupied research submersible, no way for scientists or the public to directly experience the deep ocean that shapes our state’s future.

Look, robots are incredible. MBARI’s ROVs and AUVs set global standards, and they should continue to be funded and expanded. But if you talk to veteran deep-sea biologists and geologists, they will tell you that being inside the environment changes the science.

Dr. Adam Soule, chief scientist for Deep Submergence at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) agrees, “Having a human presence in the deep sea is irreplaceable. The ability for humans to quickly and efficiently process the inherently 3D world around them allows for really efficient operations and excellent sampling potential. Besides, there is no better experience for inspiring young scientists and for ensuring that any scientist can get the most out of unmanned systems than immersing themselves in the environment.”

Some of our most prominent voices are also speaking out about the need to explore the ocean. I recently produced an hour-long episode of the PBS science program NOVA and one episode was about the new generation of submersibles being built right now by companies like Florida-based Triton Submarines. I had the privilege of talking to filmmaker and ocean explorer James Cameron, who was adamant that human participation in ocean exploration is critical to sustaining public interest and political will.

“The more you understand the ocean, the more you love the ocean, the more you’re fascinated by it, and the more you’ll fight to protect it,” Cameron told me.

Human eyes and brains pick up weak bioluminescence out of the corner of vision, pivot to follow a squid that just appeared at the edge of a light cone, or decide in the moment to pause and watch a behavior a diving team has never seen before. NOAA’s own materials explain the basic value of HOVs this way: you put scientists directly into the natural deep-ocean environment, which can improve environmental evaluation and sensory surveillance. Presence is a measurement instrument.

California is exactly where that presence would pay off. Think about Davidson Seamount, an underwater mountain larger than many national parks, added to the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary because of its ancient coral gardens and extraordinary biodiversity. We know this place mostly through ROVs, and we should keep using them, but a California HOV could carry sanctuary scientists, MBARI biologists, and students from Hopkins Marine Station or Scripps into those coral forests to make fine-scale observations, sample with delicacy, and come home with stories that move the public. Put a student in that viewport and you create a career. Put a donor there and you create a program.

Octopus Garden between research expeditions. (Photo: MBARI)

Cold seeps and methane ecology are another natural fit. Off Southern California and along the borderlands there are active methane seep fields with complex microbial and animal communities. Recent work near seeps has even turned up newly described sea spiders associated with methane-oxidizing bacteria, a striking reminder that the deep Pacific still surprises us. An HOV complements ROV sampling by letting observers linger, follow odor plumes by sight and instrument, and make rapid, in-situ decisions about fragile communities that are easy to miss on video. That kind of fine-grained exploration connects directly to California’s climate priorities, since methane processes in the ocean intersect with carbon budgets.

There are practical use cases all over the coast. A California HOV could support geohazard work on active faults and slope failures that threaten seafloor cables and coastal infrastructure. It could conduct pre- and post-event surveys at oil-and-gas seep sites in the Santa Barbara Channel to ground-truth airborne methane measurements. It could document deep-water MPA effectiveness where visual census by divers is impossible. It could make repeated visits to whale falls, oxygen minimum zone interfaces, or sponge grounds to study change across seasons.

(Photo: Scripps Institution of Oceanography at U.C. San Diego)

It could also play a crucial role in high-profile discoveries like the recent ROV surveys that revealed thousands of corroding barrels linked to mid-20th-century DDT dumping off Southern California. Those missions produced stark imagery of the problem, but a human-occupied dive would have allowed scientists to make on-the-spot decisions about barrel sampling, trace-chemical measurements, and sediment core collection, as well as to inspect surrounding habitats for contamination impacts in real time. The immediacy of human observation could help shape quicker, more targeted responses to environmental threats of this scale.

And it’s not just the seafloor that matters. Some of the most biologically important parts of the ocean lie well above the bottom. The ocean’s twilight zone, roughly 200 to 1,000 meters deep, is a vast, dimly lit layer that contains one of the planet’s largest reservoirs of life by biomass. (My dive with WHOI was done to study the ocean’s twilight zone). Every day, trillions of organisms participate in the planet’s largest migration, the diel vertical migration, moving up toward the surface at night to feed and returning to depth by day. This zone drives global carbon cycling, supports commercial fish stocks, and is home to remarkable gelatinous animals, squid, and deepwater fishes that are rarely seen in situ.

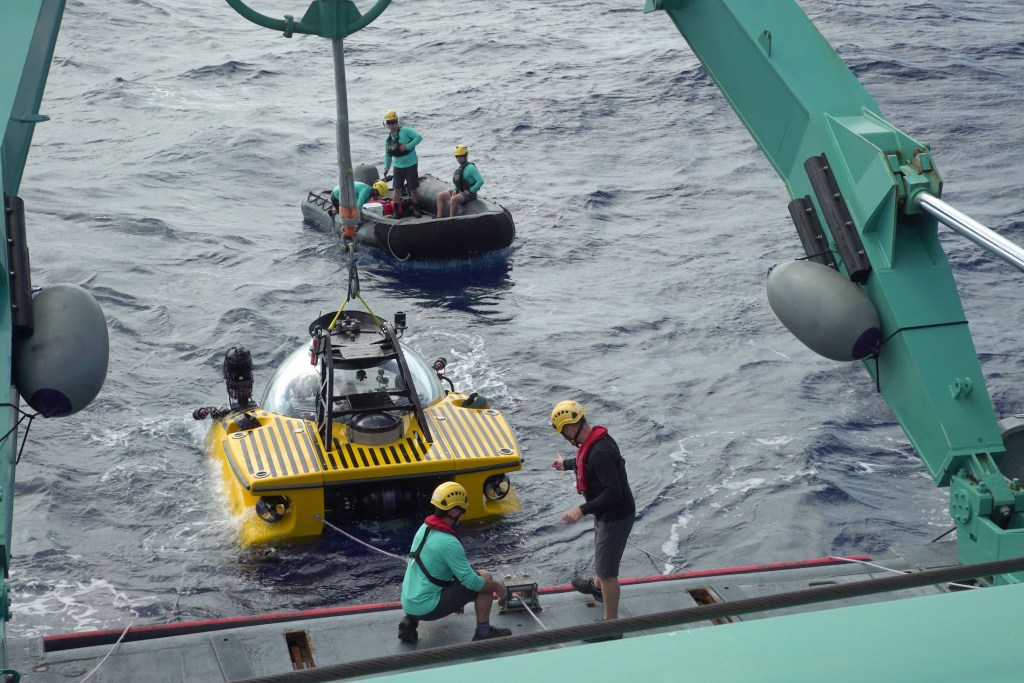

The Triton 3300/3’s 1,000-meter depth rating (I’ve been in one twice) puts the entire twilight zone within reach, enabling direct observation of these daily movements, predator-prey interactions, and delicate species that often disintegrate into goo in nets. Human presence here allows scientists to make real-time decisions to follow unusual aggregations, sample with precision, and record high-quality imagery that captures how this midwater world works, something uncrewed systems alone rarely match.

It could even serve as a classroom at depth for carefully designed outreach dives, giving educators footage and first-person accounts that no livestream can quite match. Each of these missions is stronger with people on site, conferring, pointing, deciding, and noticing.

While Monterey Bay would be a natural fit because of MBARI, Hopkins, and the sanctuary’s deepwater treasures, Southern California could be just as compelling. Catalina Island, with its proximity to submarine canyons, coral gardens, and cold seeps of the Southern California Bight, offers rich science targets and the existing facilities of USC’s Wrigley Marine Science Center. Los Angeles or Long Beach would add the advantage of major port infrastructure and a vast urban audience, making it easier to combine high-impact research with public tours, donor events, and media outreach. And San Diego with its deep naval history, active maritime industry, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, and proximity to both U.S. and Mexican waters, could serve as a southern hub for exploration and rapid response to discoveries or environmental events. These regions could even share the vehicle seasonally: Monterey in summer for sanctuary work, Catalina/LA or San Diego in winter for Southern California Bight missions, spreading both benefits and funding responsibility.

For budgeting, a proven benchmark is the Triton 3300/3, a three-person, 1,000-meter (3,300-foot) human-occupied vehicle used widely in science and filming. New units are quoted in the four to five million dollar range, with recent builds coming in around $4–4.75 million depending on specifications. Beyond the vehicle, launch and recovery systems such as a 25–30-ton A-frame or LARS and the deck integration required for a suitable support ship can run into the high six to low seven figures. Modern acrylic-sphere subs like the Triton are designed for predictable, minimized scheduled maintenance, but budgets still need to account for annual surveys, battery service, insurance, and ongoing crew training. Taken together, a California-based HOV program could be launched for an initial capital investment of roughly $6–7 million, with operating budgets scaled to the number of missions each year. So, not cheap. But doable for someone of means and purpose and curiosity. See below.

Who would benefit if California restored this capability? Everyone who already works here. MBARI operates a world-class fleet of ROVs and AUVs but has no resident HOV. Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Hopkins Marine Station, and USC’s Wrigley Marine Science Center train generations of ocean scientists who rarely get the option to do HOV work without flying across the country and waiting for a slot. NOAA and the sanctuaries need efficient ways to inspect resources and respond to events. A west-coast human-occupied research submersible based in Monterey Bay, Catalina, Los Angeles, or San Diego would plug into ship time on vessels already here, coordinate with ROV teams for hybrid dives, and cut mobilization costs for Pacific missions.

What would it take? A benefactor and a compact partnership. California has the donors (hello, curious billionaires!), companies, and public-private institutions to do this right. A philanthropic lead gift could underwrite acquisition of a proven, classed HOV and its support systems, while MBARI, Scripps, or USC could provide engineering, pilots, and safety culture within the UNOLS standards that govern HOV operations. No OceanGates. Alvin’s long record shows the model. Add a state match for workforce and student access, and a sanctuary partnership to guarantee annual science priorities, and you have a durable program that serves research, stewardship, and public engagement.

Skeptics will say that robots already do the job. They do a lot of it. They do not do all of it. If the U.S. is content to have only one deep research HOV based on the opposite coast, we will forego the unique perspectives and serendipity that only people bring, and we will keep telling California students to wait their turn or watch the ROV feed from their laptops or phones. California can do better. We did, for years, when the Delta sub spent long seasons quietly counting fish and mapping habitats off Ventura and the Channel Islands. Then that capability faded. If we rebuild it here, we restore a missing rung on the ladder from tidepools to trenches, and we align the state’s science, climate, and education missions with a tool that is both a laboratory and a conversion experience.

Start with a compact, 1,000-meter-class HOV that can work daily in most of California’s shelf and slope habitats. Pair it with our ROVs for tandem missions and cinematography of the sub and its occupants in action. Commit a share of dives to student and educator participation, recorded and repackaged for museums and broadcast. Reserve another share for rapid-response science at seeps, landslides, unusual biological events, or contamination crises like the DDT dumpsite. Build a donor program around named expeditions to Davidson Seamount, Catalina’s coral gardens, and the Channel Islands. Then, if the community wants to go deeper, plan toward a second vehicle or an upgrade path. The science is waiting. The coast is ready. And the case is clear. California should restore its human-occupied submersible fleet.