In the late 1800s, as California was emerging and gold fever captivated the public, a significant discovery in the vast, arid desert of modern-day Death Valley led to the development of a mining operation for one of the most versatile and useful materials on earth: borates.

With Hollywood and Silicon Valley dominating California’s identity, it’s easy to overlook the significant role extractive industries have played in shaping the state’s economic and industrial history. However, sites like the Rio Tinto Borax Mine in Boron, California, stand as enduring reminders of this often underappreciated chapter.

Despite the similar-sounding name, borates are far from boring. These indispensable compounds have a wide range of applications that significantly impact our daily lives. Remarkably, the mining operation in the desert of California is still active. In fact, it is one of the largest producers of borates in the world.

The evaporation ponds at the U.S. Borax Mine, used in the extraction of borates, have historically raised environmental concerns, including potential groundwater contamination and the management of hazardous waste byproducts. However, being located in a remote area far from major population centers has helped mitigate some of the risks associated with pollution, as the isolation reduces direct human exposure and minimizes immediate health impacts on surrounding communities. Additionally, the mine’s location in an arid climate helps slow the spread of contaminants in groundwater, though long-term environmental monitoring and mitigation remain critical. Efforts have also been made to manage waste responsibly and comply with environmental regulations to limit potential harm.

U.S. Borax, part of the global mining company Rio Tinto, operates California’s largest open pit mine and the largest borax mine in the world, producing nearly half the world’s borates. It is located near Boron, California, just off California State Route 58 and North of Edwards Air Force Base. While the mine’s economic importance to California has been significant for decades, the critical contributions of borates to modern society remain a largely untold story.

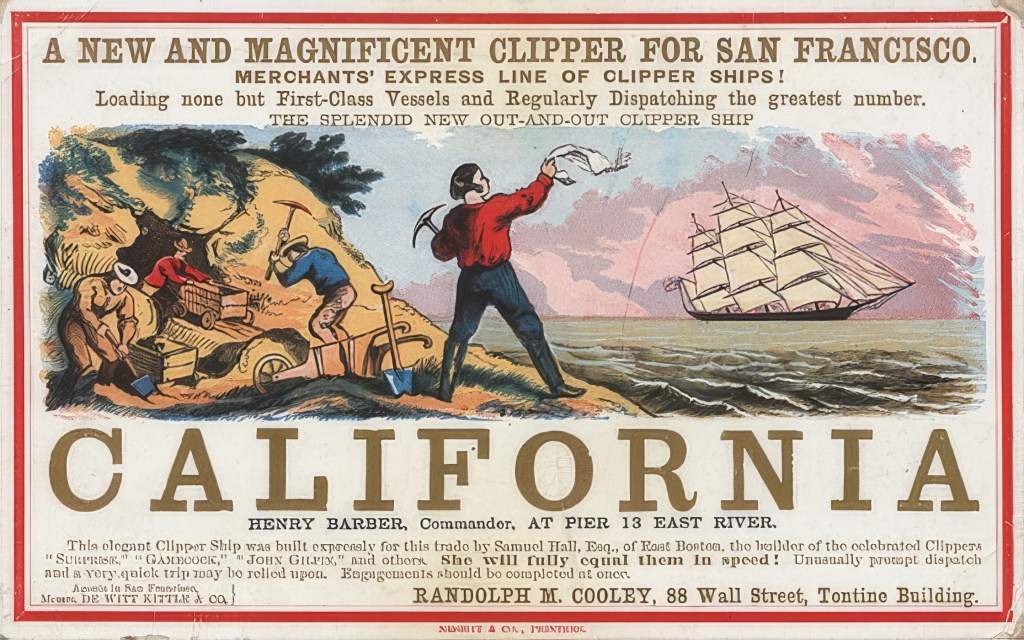

U.S. Borax has roots stretching back to the late 19th century, when the company, then called The Pacific Coast Borax Company emerged as a leader in borate mining and production following the discovery of substantial boron deposits in California. Founded by Francis Marion Smith, known as the “Borax King,” the company initially gained fame for its iconic 20 Mule Team Borax brand. The brand originated from the company’s need for an efficient way to transport borates from the remote mines in Death Valley to the nearest railhead in Mojave, California, covering a distance of about 165 miles.

To accomplish this, the company used large wagons pulled by teams of 20 mules. Each team consisted of 18 mules and 2 horses, and the wagons carried loads of up to 10 tons of borax. These mule teams became legendary for their endurance and reliability, making the long and arduous journey through the harsh desert environment.

Smith’s innovative methods and relentless pursuit of high-quality borates propelled U.S. Borax to the forefront of the industry. Over the decades, U.S. Borax has evolved, focusing on sustainable mining practices and advanced technologies to maintain its status as a key player in the global market, providing essential borate products for various industrial and consumer applications.

These versatile minerals are critical in agriculture where borates serve as micronutrients, essential for the healthy growth of crops. They are also key ingredients in detergents, where their stain-fighting power ensures cleaner, brighter clothes. Moreover, borates are used in insulation and fiberglass, contributing to energy efficiency and safety in buildings. The importance of borates extends to pharmaceuticals and cosmetics, where they serve as vital components in various formulations. But perhaps the most impactful use of borates is in the production of borosilicate glass.

You’ve likely encountered borosilicate glass before, most recognizably under the brand name Pyrex, produced by Corning. This stable, clear, and robust material can withstand a wide range of temperatures, from the intense heat of a Bunsen burner to the extreme cold of deep space.

Corning brought the future of borosilicate glass into the present by casting what was, at the time, the world’s largest primary telescope mirror. The primary mirror for the 200-inch Hale Telescope in California was cast out of Pyrex borosilicate glass and delivered to Caltech in the spring of 1936. Since manufacturing the Hale Telescope primary mirror blank, Corning has supplied many mirror blanks for astronomy tools worldwide.

Borosilicate glass is one of the unsung heroes of the modern age. Unlike regular glass, which can leach small particles into liquids when exposed to potent chemicals, borosilicate glass remains chemically inert, making it ideal for test tubes, lab beakers, and medical vials. Almost every medicine or vaccine in history, including those developed for COVID-19, has relied on borosilicate containers for their development, storage, and transport. However, we often overlook the importance of these materials until there’s a shortage.

This was the case during the COVID-19 pandemic when concerns arose that the primary obstacle to vaccine distribution might not be the pharmaceuticals themselves, but the containers needed for shipping. In response, thousands of workers along a complex supply chain—from mines to refineries to factories—helped avert a crisis. Corning even introduced a new type of glass, made with aluminum, calcium, and magnesium, to meet the high demand for medicinal vials.

The invention of borosilicate glass is credited to German chemist Otto Schott in the late 19th century. Schott was driven by the need for a type of glass that could withstand extreme temperatures and resist chemical corrosion. In 1887, he succeeded in creating this revolutionary material by adding boron oxide to traditional silica-based glass, resulting in a product with exceptional thermal and chemical stability. This breakthrough led to the founding of the Jena Glassworks, where Schott’s borosilicate glass was produced and quickly found applications in scientific and industrial settings. Its remarkable properties made it indispensable for laboratory equipment, cookware, and a variety of other uses. The material’s resilience and reliability have ensured its place as a critical component in modern science and technology, solidifying Schott’s legacy as a pioneer in glassmaking.

Due to its low coefficient of thermal expansion, borosilicate glass maintains the same optical properties across a range of temperatures, making it an ideal material for scientific lenses and other high-precision optical components, including lenses and mirrors for telescopes and microscopes.

It is also used in lighting, particularly for high-intensity lamps and projectors. Artists and craftspeople value borosilicate glass for its workability and durability in creating intricate glass sculptures and jewelry. Its robustness extends to the industrial sector, where it is used in chemical processing equipment, tubing, and sight glasses in high-temperature and corrosive environments. Overall, the unique properties of borosilicate glass make it indispensable across a wide range of applications, from everyday household items to specialized scientific and industrial equipment.

CALIFORNIA CURATED ART ON ETSY

Purchase stunning art prints of iconic California scenes.

Check out our Etsy store.

The abundance of boron in the California desert, particularly the Mojave Desert, is due to a combination of geological conditions and historical processes. Volcanic activity in the region has contributed boron-rich rocks, which, along with tectonic activity, has created basins and depressions where water could accumulate and evaporate. These conditions, coupled with the arid climate, led to the evaporation of ancient lakes and the formation of borate minerals in playas—flat, dry lakebeds that form in desert regions when water evaporates completely, leaving behind a layer of minerals. Hydrothermal activity also played a role by depositing borate minerals through fractures in the Earth’s crust. These factors collectively resulted in significant boron deposits, such as those found in the U.S. Borax boron mine, one of the world’s largest sources of boron.

The US Borax mine in Boron, California, is a fine example of some of the little-known places where California’s industrial history is laid out for all to see, even if few people probably visit. The mine highlights the ingenuity and perseverance of those who ventured into the state’s arid deserts to unearth one of the most versatile and indispensable materials known to modern industry.