While the gold rush was an incredible boon for California, hydraulic mining’s environmental toll—eroded hillsides and choked rivers—remains a stark reminder of the cost of progress.

“Earth provides enough to satisfy every man’s needs, but not every man’s greed.” — Mahatma Gandhi

“Greed is a bottomless pit which exhausts the person in an endless effort to satisfy the need without ever reaching satisfaction.” — Erich Fromm

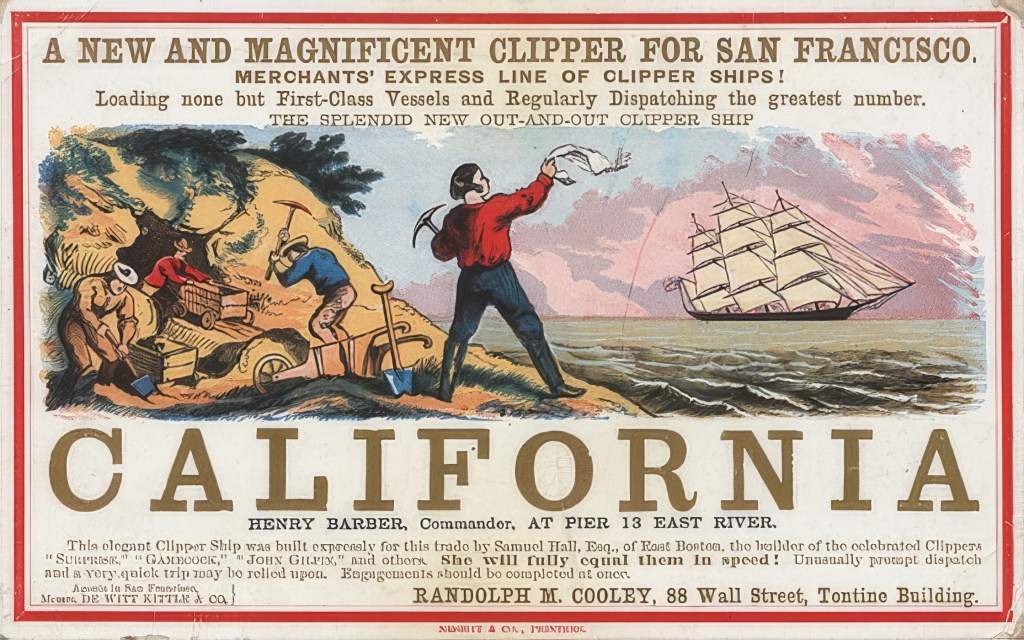

It was the tail end of the 19th century, a time of gunslingers and gold-diggers, of pioneers venturing forth into the vast expanse of the American West. The year was 1853, and the place was California. From the bustling seaports of San Francisco to the rugged mining towns dotting the Sierra Nevada foothills, the Golden State was witnessing an unprecedented phenomenon. This was the era of the California Gold Rush, a frenzy of ambition, adventure, and avarice that transformed the state and the nation.

The Gold Rush began in 1848 when gold nuggets were discovered at Sutter’s Mill in Coloma, near Sacramento. Soon after, miners from around the world rushed to California, lured by the promise of riches. But as the easily accessible placer deposits in river beds were quickly exhausted, the miners were forced to develop new, more efficient methods of extraction to mine the deeper and harder-to-reach gold seams. Thus, hydraulic mining – a form of mining that utilized high-pressure water jets to wash away soil and rock, revealing the precious metal underneath – was born.

CALIFORNIA CURATED ART ON ETSY

Purchase stunning art prints of iconic California scenes.

Check out our Etsy store.

Enter: The Innovators

Hydraulic mining in California is inextricably linked with two significant figures: Edward E. Matteson, an entrepreneurial miner, and Anthony Chabot, a young businessman turned water systems innovator. Matteson is credited as the originator of hydraulic mining in 1853, having invented the process out of necessity while trying to extract gold from the gravels of Nevada County, in a site later known as “Blue Tent.”

Matteson’s invention involved directing a powerful stream of water from a makeshift canvas hose onto a hillside, effectively washing away the dirt and gravel to expose the gold underneath. This crude but effective method marked a turning point in gold mining, facilitating the extraction of gold from areas previously deemed unprofitable or inaccessible.

However, it was Anthony Chabot who took Matteson’s idea and turned it into an industrial-scale operation. Chabot, known as the “Water King,” was a successful entrepreneur who had established multiple water systems in California. Intrigued by Matteson’s invention, he developed the hydraulic nozzle, or “monitor,” in 1855. With this high-pressure water cannon, miners could erode whole mountainsides in their search for gold, making hydraulic mining the most effective and popular method of gold extraction at that time.

The profits from hydraulic mining were enormous. As a result, the state economy boomed and many jobs were created. From 1860 to 1880, California’s mining operations yielded $170 million. San Francisco had more millionaires than New York or Boston.

The Scourge of the Sierra

From the mid-1850s to the mid-1880s, hydraulic mining reigned supreme in California, especially in the counties of Nevada, Placer, and Yuba, where extensive networks of canals, reservoirs, and sluices were constructed to support the practice. Hydraulic mines became colossal operations, employing hundreds of workers and dislodging millions of tons of earth annually. But this progress came at a tremendous cost to the environment.

The enormous water pressure used in hydraulic mining dislodged vast quantities of soil, rock, and debris, collectively referred to as “slickens.” These slickens were often laden with mercury, a neurotoxin used extensively in gold amalgamation processes. Water cannons, such as the one above, were used to wash away earth and mountains to access gold. In the early days of the gold rush, these cannons were small with canvas hoses, but more force was eventually needed. By the 1870s these cannons were anywhere from 13 to 18 feet long and could blast water 500 feet. The rivers of Northern California became choked with these toxic tailings, devastating local ecosystems.

“I am at a loss to illustrate the tremendous force with which the water is projected from the pipes. The miners assert that they can throw a stream four hundred feet into the air. … Those streams directed upon an ordinary wooden building would speedily unroof and demolish it,” wrote a reporter for the San Francisco Daily Alta.

One notable example is the Yuba River. In its heyday, hydraulic mining along the Yuba generated approximately 685 million cubic yards of debris, enough to bury Manhattan under ten feet of waste. Much of this sediment still remains, hindering river navigation and threatening local wildlife to this day. The Feather and American rivers also bear the scars of this destructive practice.

The Aftermath and Lingering Effects

By the 1870s, the catastrophic consequences of hydraulic mining were impossible to ignore. Downstream communities, most notably Marysville and Sacramento, suffered frequent and devastating floods exacerbated by mining debris. Agricultural lands were rendered useless by layers of sterile slickens, and fish populations in rivers dwindled alarmingly. The long-term health impacts of widespread mercury contamination are still being understood today.

The tension between the mining industry and the downstream farming communities ultimately culminated in the landmark case of Woodruff vs. North Bloomfield Gravel Mining Company in 1884. This case, presided over by Judge Lorenzo Sawyer, resulted in the famous “Sawyer Decision,” which effectively banned hydraulic mining due to its destructive environmental impact.

But while the Sawyer Decision marked the end of large-scale hydraulic mining, the scars left on the landscape of Northern California are far from healed. The evidence of this destruction is still visible in the stark, eroded hillsides and vast debris fields of Malakoff Diggins State Historic Park in Nevada County, once the site of California’s largest hydraulic mine.

Modern research is shedding new light on the enduring impacts of hydraulic mining. A study published in 2022 by the University of California, Davis, found that the mercury used in 19th-century mining operations has had far-reaching effects on the state’s ecosystems. Scientists discovered elevated levels of the neurotoxin in local wildlife, suggesting that the legacy of the Gold Rush continues to impact California’s environment and its inhabitants.

The Sierra Fund has introduced the Resilient Sierra Initiative to address the long-term impacts of mining in the Sierra Nevada. Their research estimates that around 26 million cubic yards of sediment remain trapped in reservoirs, which could be released as the climate changes, potentially increasing the frequency and severity of downstream flooding.

CALIFORNIA CURATED ART ON ETSY

Purchase stunning art prints of iconic California scenes.

Check out our Etsy store.

The advent of hydraulic mining during the California Gold Rush was undoubtedly a milestone in mining technology. It enabled the extraction of enormous amounts of gold and facilitated the growth and development of California. However, this innovation came with a heavy price. The ecological damage caused by hydraulic mining has left indelible marks on the landscape and continues to influence the state’s environment and communities.

Throughout history, humanity has often pursued wealth at the expense of the natural world. While some impacts are minor and fade over time, far too often, we cross a clear line without pausing to reflect on the damage we’re inflicting. Hydraulic mining in California serves as a powerful reminder: that line exists.

More information: KQED Documentary