Not So Big: How We Overstate the Length of the Blue Whale, Earth’s Largest Creature

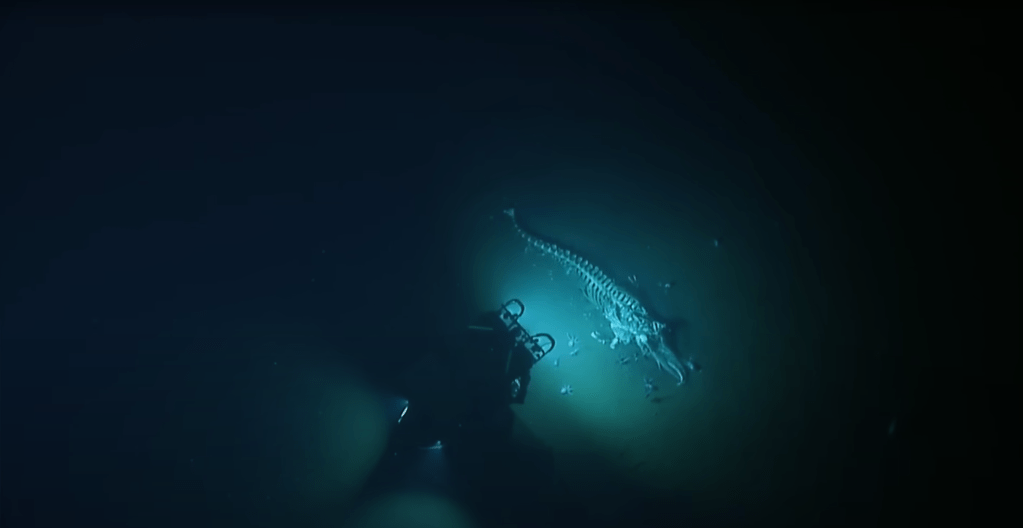

One of the most extraordinary privileges of living in California, especially near the coast, is witnessing the annual arrival of blue whales. I’ve been at sea on several occasions when these giants surfaced nearby, and to see one in person, or even through my drone RC, is astonishing and unforgettable. I once had the rare and mind-blowing opportunity to swim with and film blue whales off the southern tip of Sri Lanka for a story I wrote and produced, an experience that will forever be seared into memory.

For decades, the blue whale has been celebrated as the largest creature ever to exist (Bigger than dinosaurs! True.), with many popular accounts claiming that these animals can reach lengths of 100 feet or more. Yet in all the videos, photographs, and encounters I’ve seen, not a single whale has come close to that. Still, article after article and documentary after documentary continues to repeat the claim that blue whales “reach 100 feet or more.” Nearly every whale-watching company in California repeats the claim, echoed endlessly across Instagram and TikTok.

But is it true? Most blue whales I’ve seen off the coast of California are half that size or maybe 2/3. It felt misleading to say so otherwise. And so I did a lot of digging: reading, reaching out to experts, poring over historical records, and the fact is that no single blue whale has ever been scientifically measured at 100 feet. Close, as you will soon read, but not 100 feet or more. Especially not off the coast of California.

This discrepancy not only distorts our understanding of these magnificent creatures, but also highlights the broader issue of how media can shape and sometimes mislead public perception of scientific facts.

In other words: the perception that blue whales commonly reach lengths of 100 feet or more likely stems from a combination of historical anecdotes, estimation errors, and a tendency to highlight extreme examples.

All that said, the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) is a truly magnificent creature. Hunted nearly to extinction in the 17th to 19th centuries, the blue whale has staged a hopeful recovery in the last five decades, since commercial whaling was outlawed by the international community in 1966 (although some Soviet whale hunting continued into the early 1970s). And California, in particular, has been blessed with the annual appearance of the largest population of blue whales in the world, called the Eastern North Pacific population, consisting of some 2,000 animals. That population makes an annual migration from the warm waters of Baja California to Alaska and back every year. This is the group I’ve seen off Newport Beach.

These numbers are painfully, tragically small compared to what existed before commercial whaling began. Prior to that, it was estimated that there were some 400,000 blue whales on earth. 360,000 were killed in the Antarctic alone. (IMO: this stands as one of the most shameful acts in human history).

The International Union for Conservation of Nature estimates that there are probably between 5,000 to 15,000 blue whales worldwide today, divided among some five separate populations or groups, including the Eastern North Pacific population. Many now swim so close to shore that an entire whale-watching industry has flourished along the California coast, especially in the south, with many former fishing boats converted into whale-watching vessels..

But back to size, or, more specifically, length: there are two credible references in scientific papers of blue whales that are near 100 feet. The first is a measurement dating back to 1937. This was at an Antarctic whaling station where the animal was said to measure 98 feet. But even that figure is shrouded in some suspicion. First of all, 1937 was a long time ago, and while the size of a foot or meter has not changed, a lot of record-keeping during that time is suspect, as whales were not measured using standard zoological measurement techniques (see below). The 98-foot specimen was recorded by Lieut. Quentin R. Walsh of the US Coast Guard, who was acting as a whaling inspector of the factory ship Ulysses. Sadly, there is scant detail available about this measurement and it remains suspect in the scientific community.

The second is from a book and a 1973 paper by the late biologist Dale W. Rice, who references a single female in Antarctica whose “authenticated” measurement was also 98 feet. The measurement was conducted by the late Japanese biologist Masaharu Nishiwaki. Nishiwaki and Rice were friends, and while both are deceased, a record of their correspondence exists in a collection of Rice’s papers held by Sally Mizroch, co-trustee of the Dale W. Rice Research Library in Seattle. Reached by email, Dr. Mizroch said that Nishiwaki, who died in 1984, was a very well-respected scientist and that the figure he cited should be treated as reliable.

According to Mizroch, who has reviewed many of the Antarctic whaling records from the whaling era, whales were often measured in pieces after they were cut up, which greatly introduces the possibility for error. That is likely not the case with the 98-foot measurement, which took place in 1947 at a whaling station in Antarctica where Nishiwaki was stationed as a scientific observer.

Proper scientific measurements, the so-called “standard method”, are taken by using a straight line from the tip of the snout to the notch in the tail flukes. This technique was likely not used until well into the 20th century, said Mizroch. In fact, it wasn’t until the 1940s that the use of a metal tape measure became commonplace. According to Dan Bortolotti, author of Wild Blue: A Natural History of the World’s Largest Animal, many of the larger whales in the whaling records — especially those said to be over 100 feet — were probably measured incorrectly or even deliberately exaggerated because bonus money was paid to whalers based on the size of the animal caught.

So, according to the best records we have, the largest blue whale ever properly measured was 98 feet long. Granted, 98 feet is close to 100 feet, but it’s not 100 feet, and it’s certainly not over 100 feet, as so many otherwise reputable references state.

So, setting aside the fact that so many sources say the blue whale has reached 100 feet or more, and that there is no scientific evidence proving this, a key question to ask is how large can whales become?

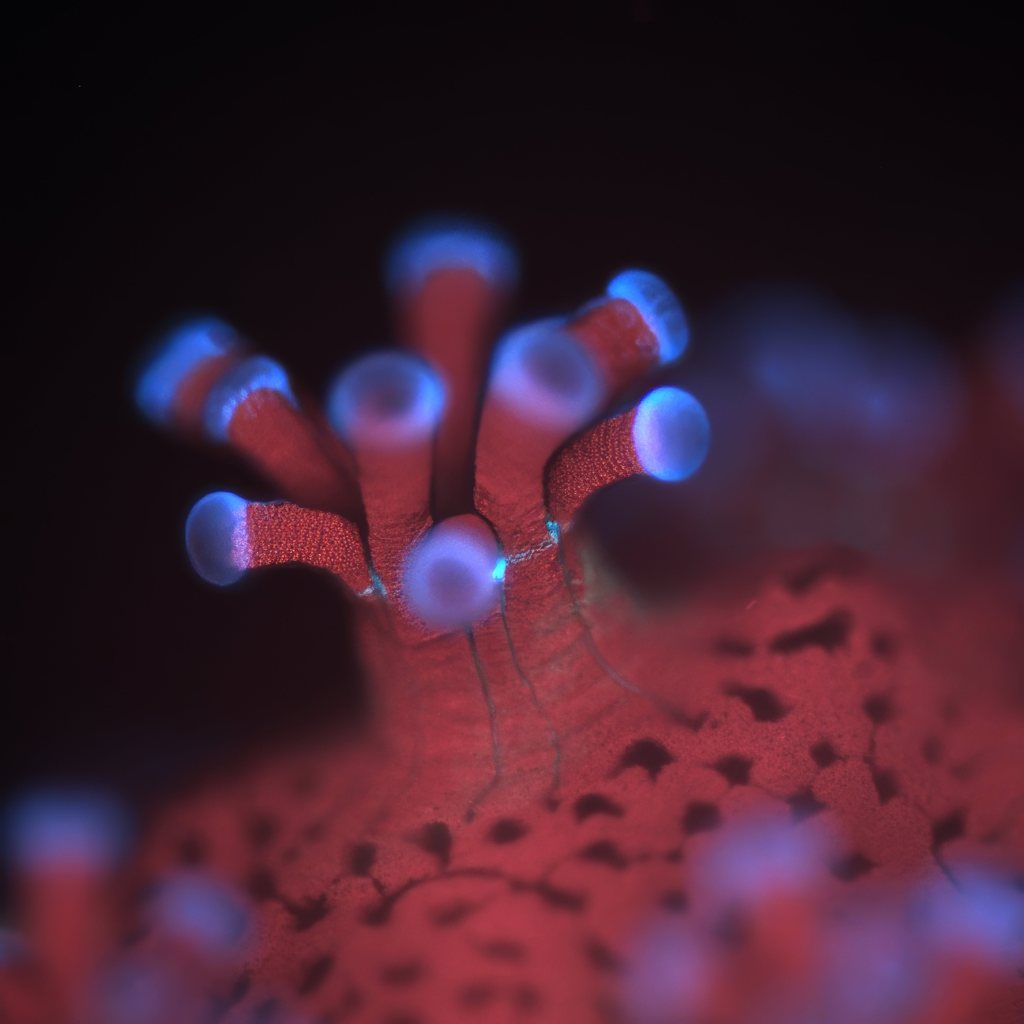

Most baleen whales are so-called lunge feeders. They open their mouths wide and lunge at prey like krill or copepods, drawing in hundreds of pounds of food at a time. Lunge-feeding baleen whales, it turns out, are wonderfully efficient feeders. The larger they become, the larger their gulps are, and the more food they draw in. But they also migrate vast distances, and oftentimes have to dive deep to find prey, both of which consume a large amount of energy.

A 2019 scientific paper in Science described how a team of researchers used an ocean-going Fitbit-like tag to track whales’ foraging patterns, hoping to measure the animals’ energetic efficiency, or the total amount of energy gained from foraging, relative to the energy expended in finding and consuming prey. The team concluded that there are likely ecological limits to how large a whale can become and that maximum size in filter feeders “is likely constrained by prey availability across space and time.” That is especially the case in today’s era, when overfishing and illegal fishing, including krill harvesting in Antarctica, have reduced the amount of prey available even in regions that used to be very prolific.

John Calambokidis, a Senior Research Biologist and co-founder of Cascadia Research, a non-profit research organization formed in 1979 based in Olympia, Washington, has studied blue whales up and down the West Coast for decades. He told California Curated that the persistent use of the 100-foot figure can be misleading, especially when the number is used as a reference to blue whales off the coast of California.

The sizes among different blue whale groups differ significantly depending on their location around the globe. Antarctic whales tend to be much bigger, largely due to the amount of available food in cold Southern waters. The blue whales we see off the coast of California, Oregon, Washington and Alaska, are part of a different group from those in Antarctica. They differ both morphologically and genetically, and they consume different types and quantities of food. North Pacific blue whales, our whales, tend to be smaller and likely have always been so. Calambokidis believes that the chances any blue whales off the West Coast of the US ever reaching anything close to 100 feet is “almost non-existent”.

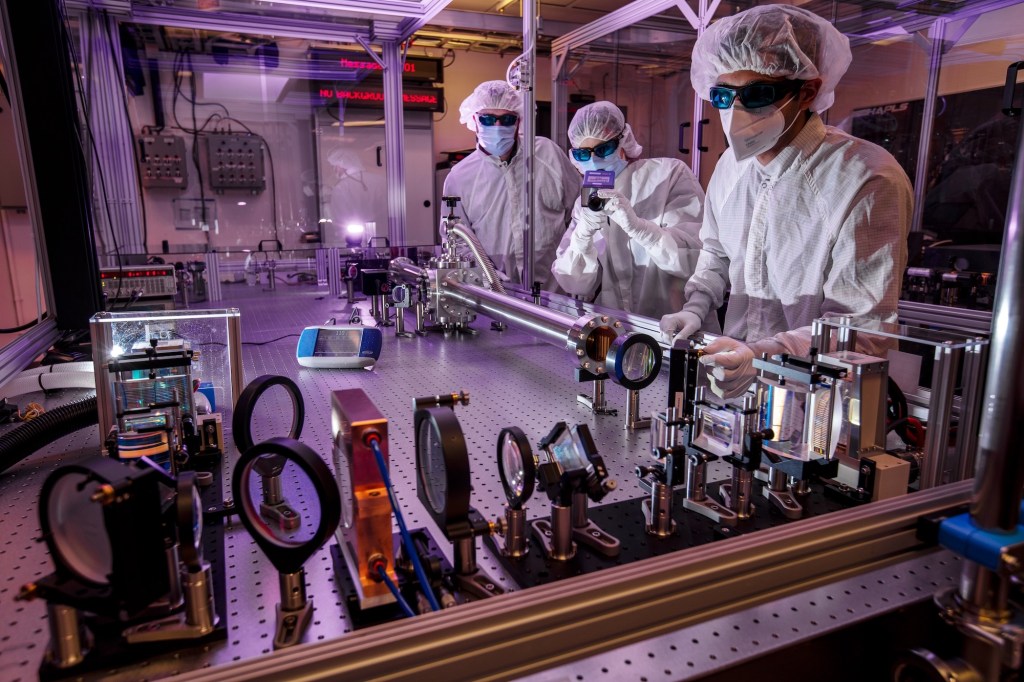

I emailed Regina Asmutis-Silvia, Executive Director North America of Whale and Dolphin Conservation, to ask about this discrepancy among so many seemingly authoritative outlets. She wrote: “While it appears biologically possible for blue whales to reach or exceed lengths of 100’, the current (and limited) photogrammetry data suggest that the larger blue whales which have been more recently sampled are under 80 feet.” Photogrammetry is the process of using several photos of an object — like a blue whale — to extract a three-dimensional measurement from two-dimensional data. It is widely used in biology, as well as engineering, architecture, and many other disciplines. Photogrammetry measurements are now often acquired by drones and have proven to be a more accurate means of measuring whale size at sea.

Here’s a key point: In the early part of the 20th century and before, whales were measured by whalers for the purpose of whaling, not measured by scientists for the purpose of science. Again, none of this is to say that blue whales aren’t gargantuan animals. They are massive and magnificent, but if we are striving for precision, it is not accurate to declare, as so many articles and other media do, that blue whales reach lengths of 100 feet or more. Or to insinuate that this size is in any way common. This is not to say it’s impossible that whales grew to or above 100 feet, it’s that, according to the scientific records, none ever has.

A relevant point from Dr. Asmutis-Silvia about the early days of Antarctic whaling: “Given that whales are long-lived and we don’t know at what age each species reaches its maximum length, it is possible that we took some very big, very old whales before we started to measure what we were taking.”

In an email exchange with Jeremy Goldbogen, the scientist at Stanford who authored the study in Science above, he says that measurements with drones off California “have been as high as 26 meters” or 85 feet.

So, why does nearly every citation online and elsewhere regularly cite the 100-foot number? It probably has to do with our love of superlatives and round numbers. We have a deep visceral NEED to be able to say that such and such animal is the biggest or the heaviest or the smallest or whatever. And, when it comes down to it, 100 feet is a nice round number that rolls easily off the tongue or typing fingers.

All said, blue whales remain incredible and incredibly large animals, and deserve our appreciation and protection. Their impressive rebound over the last half-century is to be widely celebrated, but let’s not, in the spirit of scientific inquiry, overstate their magnificence. They are magnificent enough.