It is no coincidence that “Eureka” is the state motto of California. From its founding, the state has been a hub of groundbreaking discoveries, from the Gold Rush to advancements in space exploration, the rise of Silicon Valley and the development of modern computing, the development of seismic science, and the confirmation of the accelerating expansion of the universe. But one discovery made at the University of California, Berkeley, changed the way we see the world—or at least how it was almost destroyed, along with a huge part of life on the planet.

In 1977, Walter Alvarez arrived at Berkeley with rock samples from a small Italian town called Gubbio, unaware that they would help rewrite the history of life on Earth. He had spent years studying plate tectonics, but his father, Luis Alvarez, a Nobel Prize-winning physicist known for his unorthodox problem-solving at Berkeley, would propel him into a new kind of investigation, one deeply rooted in geology and Earth sciences. Their work led to one of the most significant scientific breakthroughs of the 20th century: the discovery that a massive meteorite impact was responsible for the extinction of the dinosaurs and much of life on Earth.

The samples Walter had collected contained a puzzling clay layer sandwiched between older and younger limestone deposits. This clay was rich in iridium—an element rare on Earth’s surface. The discovery of such an unusually high concentration of iridium in a single layer of buried rock was perplexing. Given that iridium is far more common in extraterrestrial bodies than on Earth’s surface, its presence suggested an extraordinary event—one that had no precedent in scientific understanding at the time. The implications were staggering: if this iridium had arrived all at once, it pointed to a cataclysmic event unlike anything previously considered in Earth’s history. Although some scientists had speculated about meteor impacts, solid evidence was scarce.

Alvarez determined that this layer corresponded precisely to the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) boundary (formerly called Cretaceous–Tertiary or K–T boundary), the geological marker of the mass extinction that eradicated the non-avian dinosaurs 66 million years ago. Scientists had long debated the cause of this catastrophe, proposing theories ranging from volcanic activity to gradual climate change. But the Alvarez team would introduce a radical new idea—one that required looking beyond Earth.

Mass extinctions stand out so distinctly in the fossil record that the very structure of geological time is based on them. In 1841, geologist John Phillips divided life’s history into three chapters: the Paleozoic, or “ancient life”; the Mesozoic, or “middle life”; and the Cenozoic, or “new life.” These divisions were based on abrupt breaks in the fossil record, the most striking of which were the end-Permian extinction and the end-Cretaceous extinction, noted here. The fossils from these three eras were so different that Phillips originally believed they reflected separate acts of creation. Charles Lyell, one of the founders of modern geology, observed a “chasm” in the fossil record at the end of the Cretaceous period, where species such as belemnites, ammonites, and rudist bivalves vanished entirely. However, Lyell and later Charles Darwin dismissed these apparent sudden extinctions as mere gaps in the fossil record, preferring the idea of slow, gradual change (known as gradualism, versus catastrophism). Darwin famously compared the fossil record to a book where only scattered pages and fragments of lines had been preserved, making abrupt transitions appear more dramatic than they were.

Luis Alvarez was a physicist whose career had spanned a remarkable range of disciplines, from particle physics to aviation radar to Cold War forensics. He had a history of bold ideas, from using muon detectors to search for hidden chambers in pyramids to testing ballistic theories in the Kennedy assassination with watermelons. When Walter shared his perplexing stratigraphic findings, Luis proposed a novel method to measure how long the clay layer had taken to form: by analyzing its iridium content.

As discusses, Iridium is a rare element on Earth’s surface but is far more abundant in meteorites. Luis hypothesized that if the clay had accumulated slowly over thousands or millions of years, it would contain only tiny traces of iridium from cosmic dust. But if it had been deposited rapidly—perhaps by a single catastrophic event—it might show an anomalously high concentration of the element. He reached out to a Berkeley colleague, Frank Asaro, whose lab had the sophisticated equipment necessary for this kind of analysis.

Nine months after submitting their samples, Walter received a call. Asaro had found something extraordinary: the iridium levels in the clay layer were off the charts—orders of magnitude higher than expected. No one knew what to make of this. Was it a weird anomaly, or something more significant? Walter flew to Denmark to collect some late-Cretaceous sediments from a set of limestone cliffs known as Stevns Klint. At Stevns Klint, the end of the Cretaceous period shows up as a layer of clay that’s jet black and contains high amounts of organic material, including remnants of ancient marine life. When the stinky Danish samples were analyzed, they, too, revealed astronomical levels of iridium. A third set of samples, from the South Island of New Zealand, also showed an iridium “spike” right at the end of the Cretaceous. Luis, according to a colleague, reacted to the news “like a shark smelling blood”; he sensed the opportunity for a great discovery.

The Alvarezes batted around theories. But all the ones they could think of either didn’t fit the available data or were ruled out by further tests. Then, finally, after almost a year’s worth of dead ends, they arrived at the impact hypothesis. On an otherwise ordinary day sixty-six million years ago, an asteroid six miles wide collided with the Earth. Exploding on contact, it released energy on the order of a hundred million megatons of TNT, or more than a million of the most powerful H-bombs ever tested. Debris, including iridium from the pulverized asteroid, spread around the globe. Day turned to night, and temperatures plunged. A mass extinction ensued. Even groups that survived, like mammals and lizards, suffered dramatic die-offs in the aftermath. Who perished, and who survived, set the stage for the next 66 million years—including our own origin 300,000 years ago.

The Alvarezes wrote up the results from Gubbio and Stevns Klint and sent them, along with their proposed explanation, to Science. “I can remember working very hard to make that paper just as solid as it could possibly be,” Walter later recalled. Their paper, Extraterrestrial Cause for the Cretaceous-Tertiary Extinction, was published in June 1980. It generated enormous excitement, much of it beyond the bounds of paleontology, but it was also ridiculed by some who considered the idea far-fetched, if not ridiculous. Journals in disciplines ranging from clinical psychology to herpetology reported on the Alvarezes’ findings, and soon the idea of an end-Cretaceous asteroid was picked up by magazines like Time and Newsweek. In an essay in The New York Review of Books, the late American paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould quipped that linking dinosaurs—long an object of fascination—to a major cosmic event was “like a scheme a clever publisher might devise to ensure high readership.”

Inspired by the impact hypothesis, a group of astrophysicists led by Carl Sagan decided to try to model the effects of an all-out war and came up with the concept of “nuclear winter,” which, in turn, generated its own wave of media coverage. But as the discovery sank in among many professional paleontologists, the Alvarezes’ idea—and in many cases, the Alvarezes themselves—were met with hostility. “The apparent mass extinction is an artifact of statistics and poor understanding of the taxonomy,” one paleontologist told The New York Times. “The arrogance.”

Skepticism was immediate and intense. Paleontologists, geologists, and physicists debated the implications of the iridium anomaly. But as the search for supporting evidence intensified, the pieces of the puzzle began to fall into place. Shocked quartz, a telltale sign of high-energy impacts, was found at sites around the world. Soot deposits suggested massive wildfires had raged in the aftermath.

In the early 1990s, conclusive evidence finally emerged. The Chicxulub crater, measuring roughly 180 kilometers across and buried under about half a mile of sediment in Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, was identified as the likely impact site. Although it was first detected by Mexico’s state-run oil company (PEMEX) in the 1950s during geophysical surveys, core samples taken decades later clinched the identification of Chicxulub as the long-sought impact site linked to the mass extinction that ended the Cretaceous era.

One of the more intriguing (if not astounding) recent discoveries tied to the end-Cretaceous impact is a site called Tanis, located in North Dakota’s Hell Creek Formation. Discovered in 2019 by a team led by Robert DePalma and spotlighted in a New Yorker article, Tanis preserves a remarkable snapshot of what appears to be the immediate aftermath of the asteroid strike.

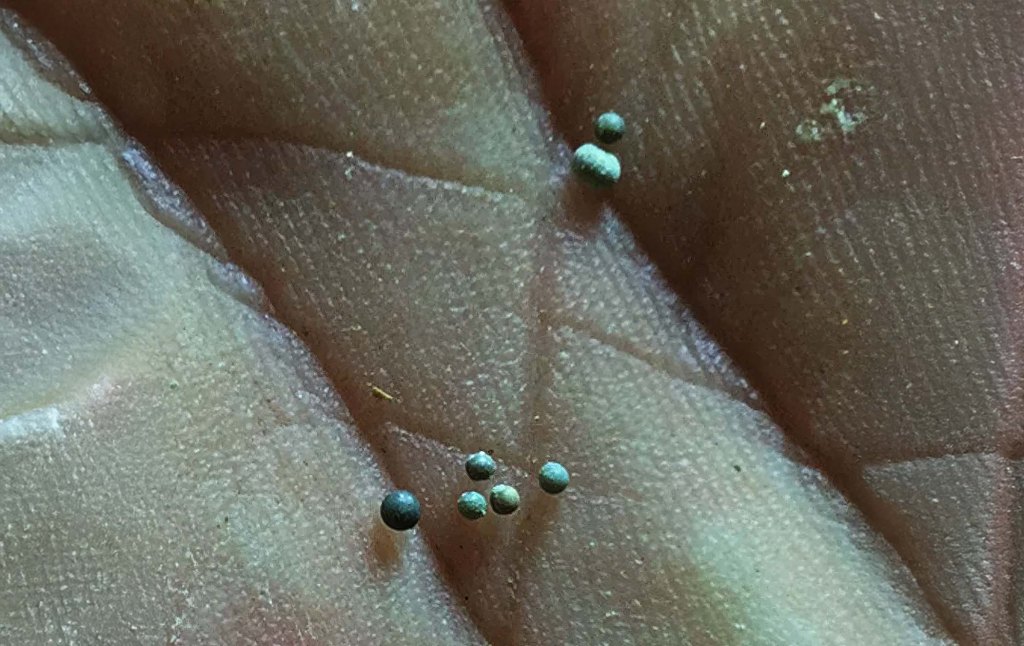

The sedimentary layers at Tanis indicate large waves—often called “seiche waves”—that may have surged inland in the immediate aftermath of the impact. They also contain countless tiny glass spherules that rained down after the explosion. Known as microtektites, these blobs form when molten rock is hurled into the atmosphere by an asteroid collision and solidifies as it falls back to Earth. The site appears to hold them by the millions. In some cases, fish fossils have been found with these glass droplets lodged in their gills—a striking testament to how suddenly life was disrupted.

Although still under investigation, Tanis has drawn attention for its exceptional level of detail, potentially capturing events that took place within mere hours of the impact. The precise interpretation of this site continues to spark controversy among researchers. There is also controversy about the broader cause of the mass extinction itself: the main competing hypothesis is that the colossal “Deccan” volcanic eruptions, in what would become India, spewed enough sulfur and carbon dioxide into the atmosphere to cause a dramatic climatic shift. However, the wave-like deposits, along with the abundant glass spherules, suggest a rapid and violent disturbance consistent with a massive asteroid strike. Researchers hope to learn more about the precise sequence of disasters that followed—tidal waves, intense firestorms, and global darkness—further fleshing out the story of how the world changed so drastically, so quickly.

All said, today the Alvarez hypothesis is widely accepted as the leading explanation for the K-Pg mass extinction. Their contributions at UC Berkeley—widely recognized as one of the world’s preeminent public institutions—not only reshaped our understanding of Earth’s history but also changed how we perceive planetary hazards. The realization that cosmic collisions have shaped life’s trajectory has led to renewed interest in asteroid detection and planetary defense.

Walter and Luis Alvarez’s discovery was a testament to the power of interdisciplinary science and the willingness to follow unconventional ideas. Their pursuit of an extraterrestrial explanation for a terrestrial mystery reshaped paleontology, geology, and astrophysics. What began with a father and son pondering an ancient Italian rock layer ended in a revelation that forever changed how we understand the history of life—and its vulnerability to forces from beyond our world.