The Vital Role of Upwelling in California’s Rich Ocean Life

Few marine processes have been as impactful on the abundance of sea life off the coast of California as upwelling. It may not be a term you’ve heard before, but the natural oceanic process of upwelling is one of the most important engines driving climate, biological diversity, and the ocean’s food web. It’s time to pay attention.

In simple terms, upwelling happens when deep, cold, nutrient-laden water moves toward the ocean surface, replacing the warm surface water. Along the California coast, it’s fueled by the California Current, which flows southward, and by prevailing northerly winds. The wind pushes surface water offshore, allowing the deeper water to well up and take its place. This isn’t just an abstract idea; it’s been studied extensively.

In California, upwelling occurs year-round off the northern and central coast. It’s strongest in the spring and summer when northwesterly winds are at their most powerful. Upwelling is reduced in the fall and winter when winds are more variable.

Researchers from institutions like the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and Stanford University have used a variety of methods, including satellite observations and computer modeling, to study upwelling. One of the groundbreaking studies was the CalCOFI program (California Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries Investigations), which began in the late 1940s. It was a joint venture between Scripps and state and federal agencies to investigate the collapse of the sardine fishery. Over decades, it has expanded its scope and now provides invaluable long-term datasets that help scientists understand the dynamics of upwelling and its effects on marine populations.

CALIFORNIA CURATED ART ON ETSY

Purchase stunning art prints of iconic California scenes.

Check out our Etsy store.

The key to understanding the phenomenon of upwelling off the California coast begins with the importance of cold water. In colder regions, nutrients from the deeper layers of the ocean are more readily brought to the surface through various oceanic processes like upwelling, tidal action, and seasonal mixing.

Think of a well-fertilized garden versus a nutrient-poor one. In the former, you’d expect a lush array of plants that not only thrive, but also support a diversity of insect and animal life. Similarly, the nutrient-rich cold waters support “blooms” of phytoplankton, a critical component of the oceanic food web. Phytoplankton are microscopic, photosynthetic organisms that form the foundation of aquatic food webs, producing oxygen and serving as a primary food source for marine life. When these primary producers flourish, it sets off a chain reaction throughout the ecosystem. Zooplankton (tiny ocean-borne animals like krill) feast on phytoplankton, small fish feast on zooplankton, and larger predators, including larger fish, marine mammals, and seabirds, find an abundant food supply in these teeming waters.

Moreover, cold water has a higher capacity to hold dissolved gases like oxygen compared to warm water (one of the reasons that warming seas could be a problem in the future). Oxygen is a key factor for respiration in marine animals. In cold, oxygen-rich environments, organisms can efficiently carry out metabolic processes, which often results in higher rates of feeding, growth, and reproduction, thereby further boosting biological productivity.

A recent study has also shed light on how California’s rich marine ecosystem responds to climate patterns, particularly the El Niño and La Niña phases of the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Scientists found that during El Niño events, warmer waters and weaker upwelling lead to reduced nutrient levels in the California Current, which supports less phytoplankton and affects the entire food web, including fish populations. In contrast, La Niña conditions boost upwelling, bringing nutrient-rich waters to the surface and enhancing marine productivity. This research highlights the far-reaching impacts of climate cycles on ocean life and could help in forecasting changes that affect fisheries and marine biodiversity in California.

Studies have also shown the direct correlation between the intensity of upwelling and the success of fish populations. A study published in the journal “Science Advances” in 2019 explored how variations in upwelling affect the foraging behavior and success of California sea lions. Researchers found that in years with strong upwelling, sea lions didn’t have to travel as far to find food, which, in turn, positively impacted their population’s health.

Upwelling is a critical oceanic process that helps maintain the stable and immensely productive California marine ecosystem, but there are serious concerns that the dynamics behind upwelling could be changing due to climate change.

Of course, upwelling isn’t just a California thing; it’s a global phenomenon that occurs in various parts of the world, from the coasts of Peru to the Canary Islands. But California is like the poster child, thanks to extensive research and its vital role in a multi-billion dollar fishing industry that includes coveted species like albacore tuna, swordfish, Dungeness crab, squid, and sardines.

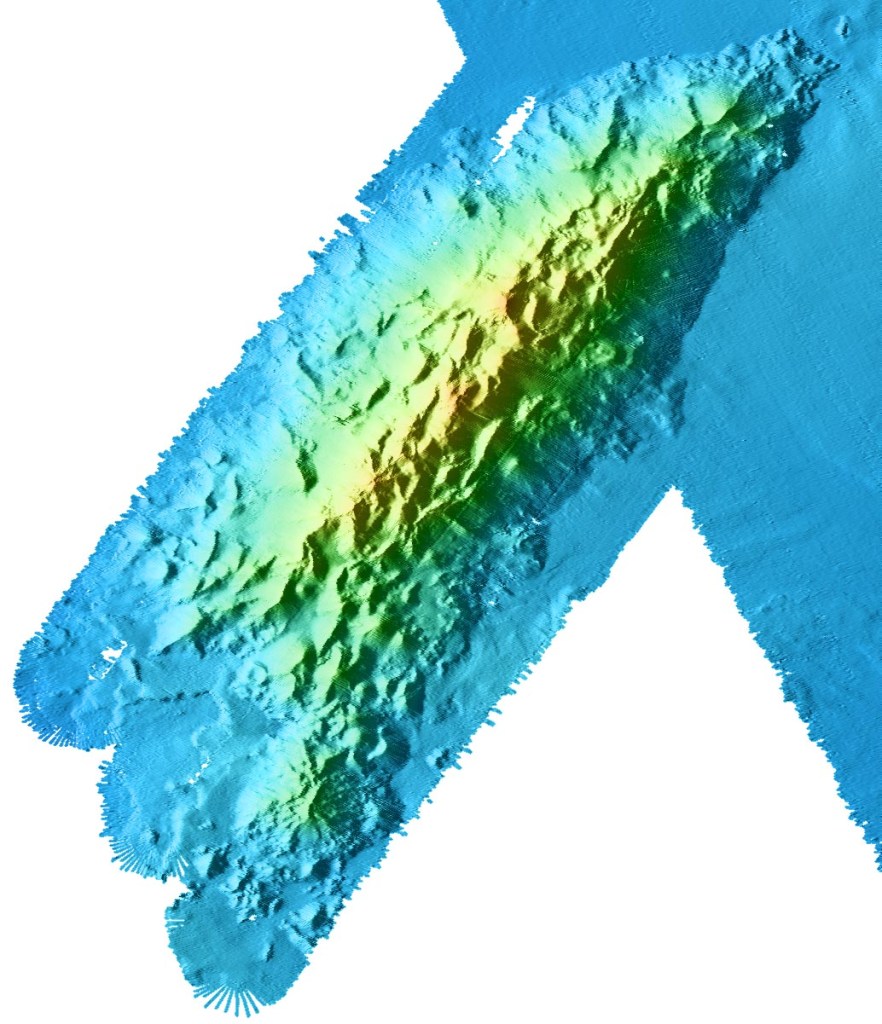

The Channel Islands provide an excellent example of a place off the California coast where the impacts of upwelling and ocean currents are particularly significant. Channel Islands National Park is uniquely located in a “transition zone” of less than 100 km where many ocean currents converge. This results in strikingly different ocean conditions at individual islands and affects where different species are found and how abundant they are.

Long-term studies of upwelling and the California Current system have shed further light on the importance of these complex and ever changing phenomenon. For example, the annual California Current Ecosystem Status Report captures the big picture of the biology, climate, physical, and social conditions of the marine ecosystem. In 2021, the California Current continued a recent cooling trend, with researchers recording the coldest conditions on the continental shelf in nearly a decade. These cooler coastal waters resulted from strong wind-driven upwelling—nutrient-rich, deep ocean water coming to the surface.

But things have grown more precarious in the north and out to sea. For the last ten years, the northeast Pacific Ocean has been a hotspot for marine heatwaves. Just this past year, scientists monitored the seventh most intense marine heatwave in this region since records began in 1982. However, there was a twist in the tale: unlike in previous years, the elevated water temperatures remained further offshore, a phenomenon partly attributable to stronger-than-average coastal upwelling. As a result, the strip of waters closer to the coast was able to maintain its cooler temperatures, thereby preserving a productive environment for marine life.

Visit the California Curated store on Etsy for original prints showing the beauty and natural wonder of California.

Upwelling is a critical oceanic process that helps maintain the stable and immensely productive California marine ecosystem, but there are serious concerns that the dynamics behind upwelling could be changing due to climate change. Warming ocean temperatures and changes in wind patterns could potentially disrupt the timing and intensity of upwelling, putting the bounty of California’s coast at risk.

Understanding these shifts is imperative for devising strategies to mitigate adverse effects on marine life and commercial fisheries. Therefore, sustained research efforts must continue to dissect this complex (and incredibly important) oceanic process and its increasingly uncertain future.