Images from the most powerful astronomical discovery machine ever created, and built in California

(Credit: NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory)

I woke up this morning to watch a much-anticipated press conference about the release of the first images from the Vera Rubin Telescope and Observatory. It left me flabbergasted: not just for what we saw today, but for what is still to come. The images weren’t just beautiful; they hinted at a decade of discovery that could reshape what we know about the cosmos.I just finished watching and have to catch my breath. What lies ahead is very, very exciting.

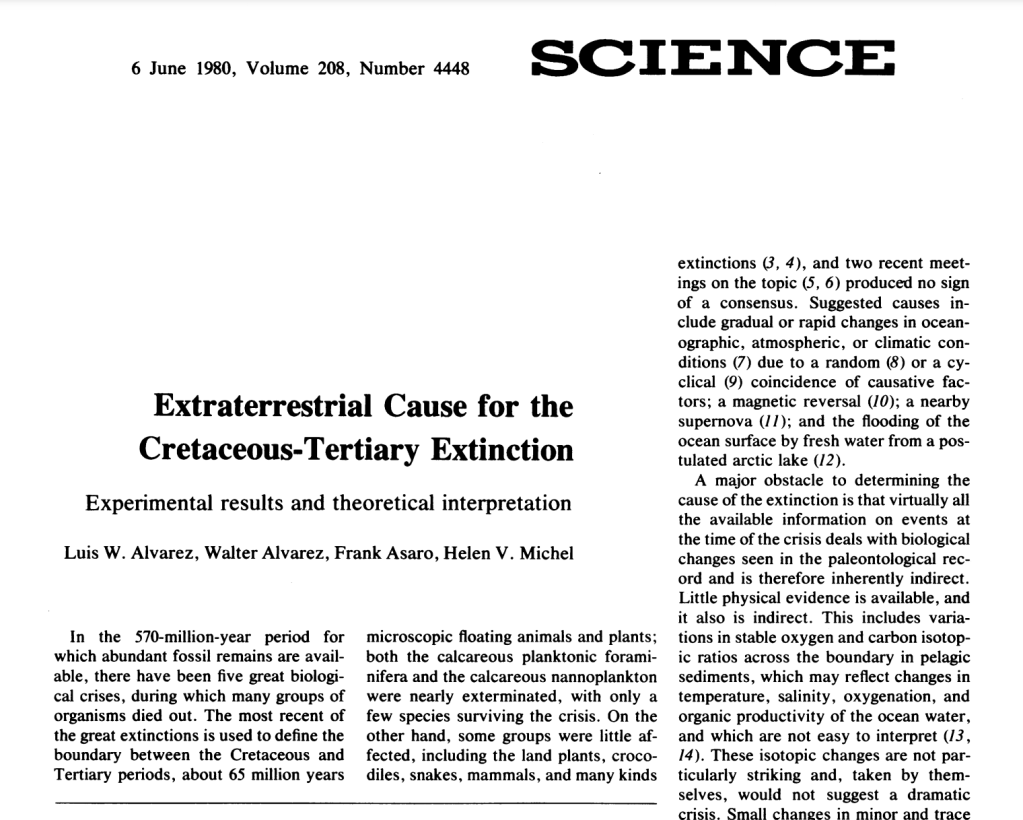

The first images released today mark the observatory’s “first light,” the ceremonial debut of a new telescope. These images are the result of decades of effort by a vast and diverse global team who together helped build one of the most advanced scientific instruments ever constructed. In the presser, Željko Ivezić, Director of the Rubin Observatory and the guy who revealed the first images, called it “the greatest astronomical discovery machine ever built.”

(Credit: NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory)

The images shown today are a mere hors d’oeuvre of what’s to come, and you could tell by the enthusiasm and giddiness of the scientists involved how excited they are about what lies ahead. Here’s a clip of Željko Ivezić as the presser ended. It made me laugh.

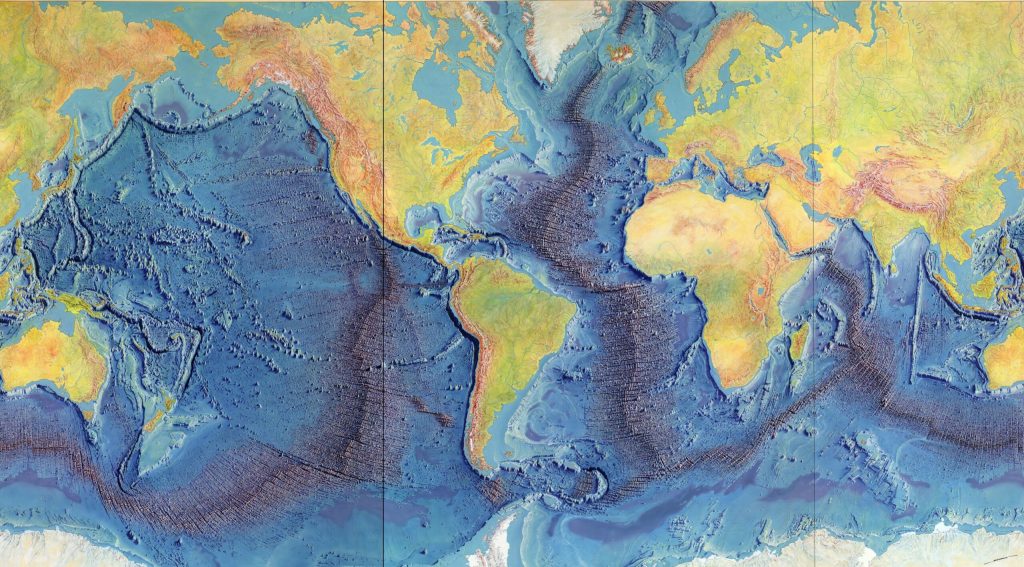

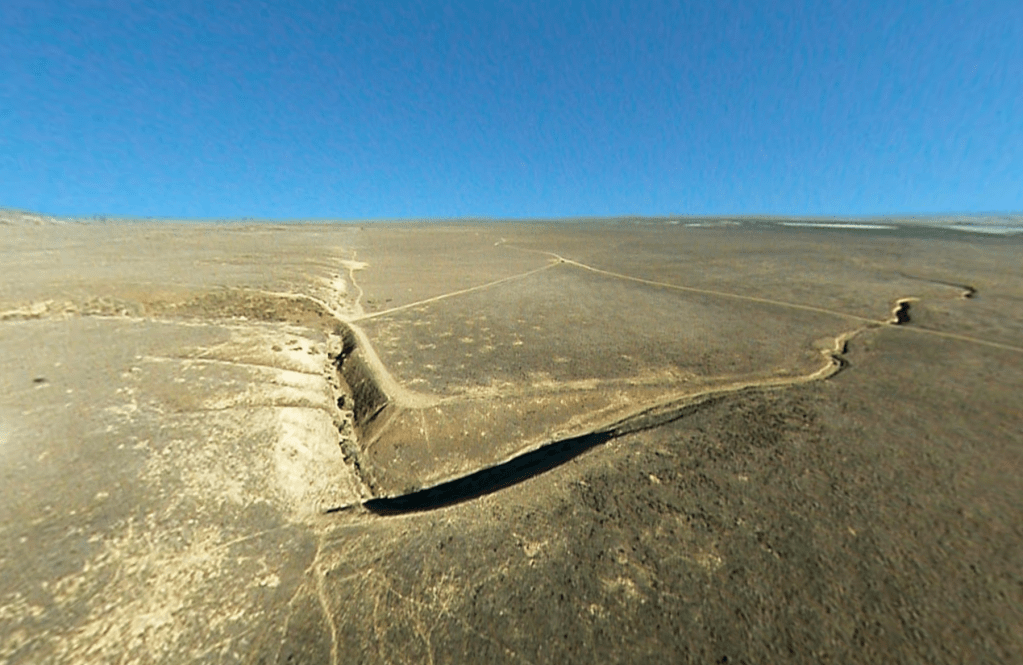

So, that first image you can see above. Check out the detail. What would normally be perceived as black, empty space to us star-gazing earthlings shows anything but. It shows that in each tiny patch of sky, if you look deep enough, galaxies and stars are out there blazing. If you know the famous Hubble Deep Field image, later expanded by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, you may already be aware that there is no such thing as empty sky. The universe contains so much stuff, it is truly impossible for our brains (or at least my brain) to comprehend. Vera Rubin will improve our understanding of what’s out there and what we’ve seen before by orders of magnitude.

(Credit: NSF–DOE Vera C. Rubin Observatory)

I’ve been following the Rubin Observatory for years, ever since I first spoke with engineers at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory about the digital camera they were building for a potential story for an episode of the PBS show NOVA that I produced (sadly, the production timeline ultimately didn’t work out). SLAC is one of California’s leading scientific institutions, known for groundbreaking work across fields from particle physics to astrophysics. (We wrote about it a while back.)

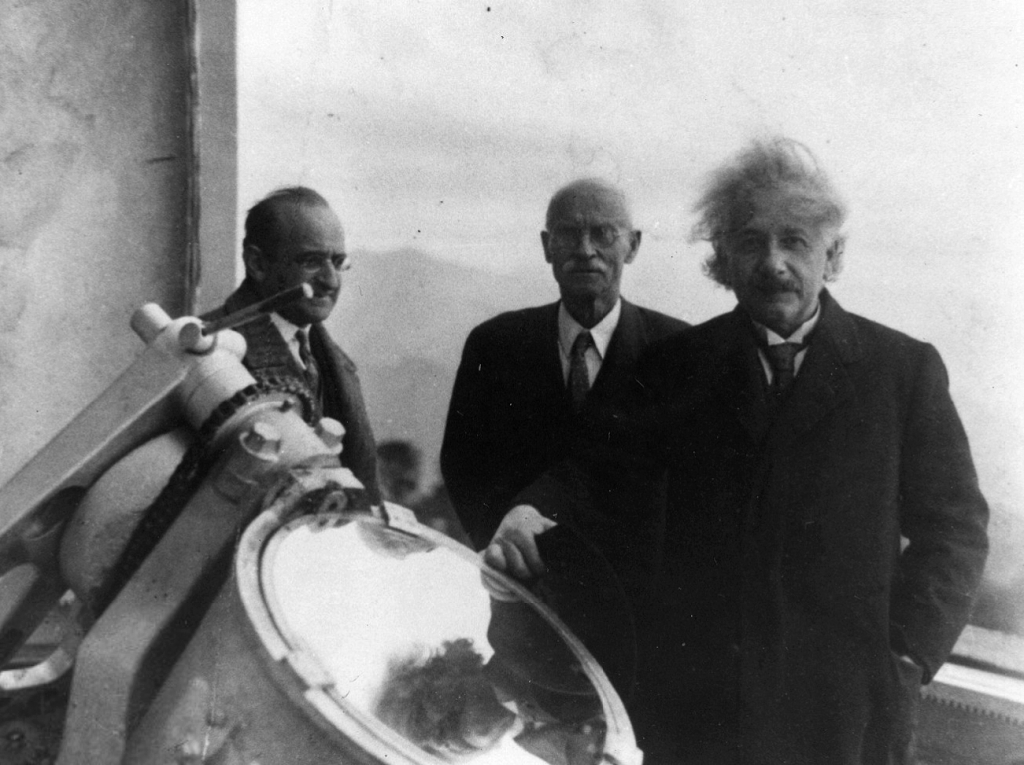

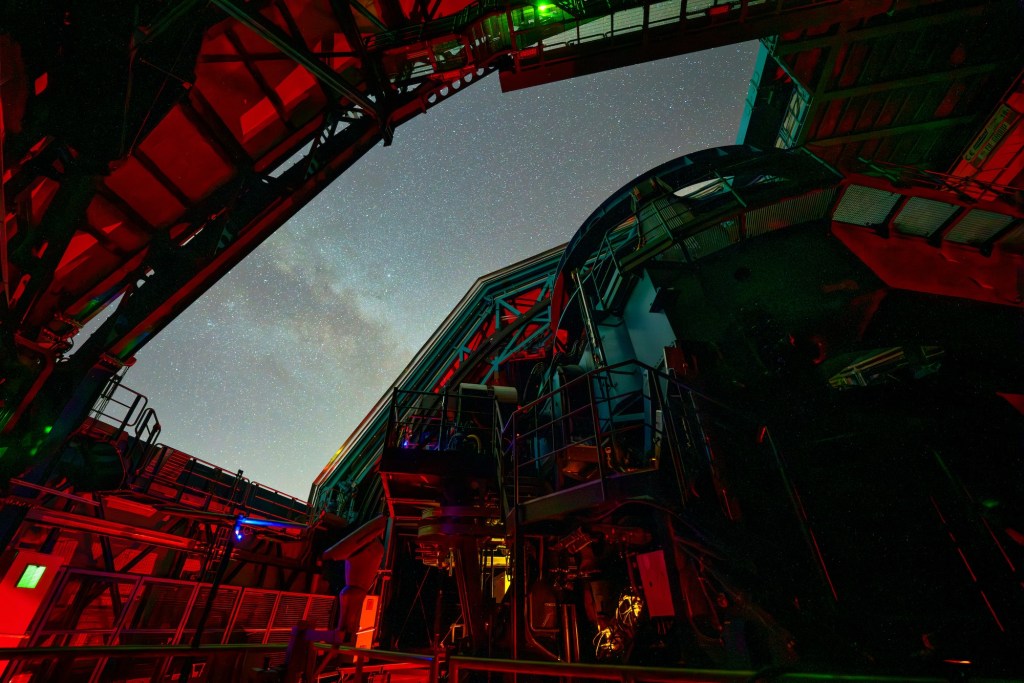

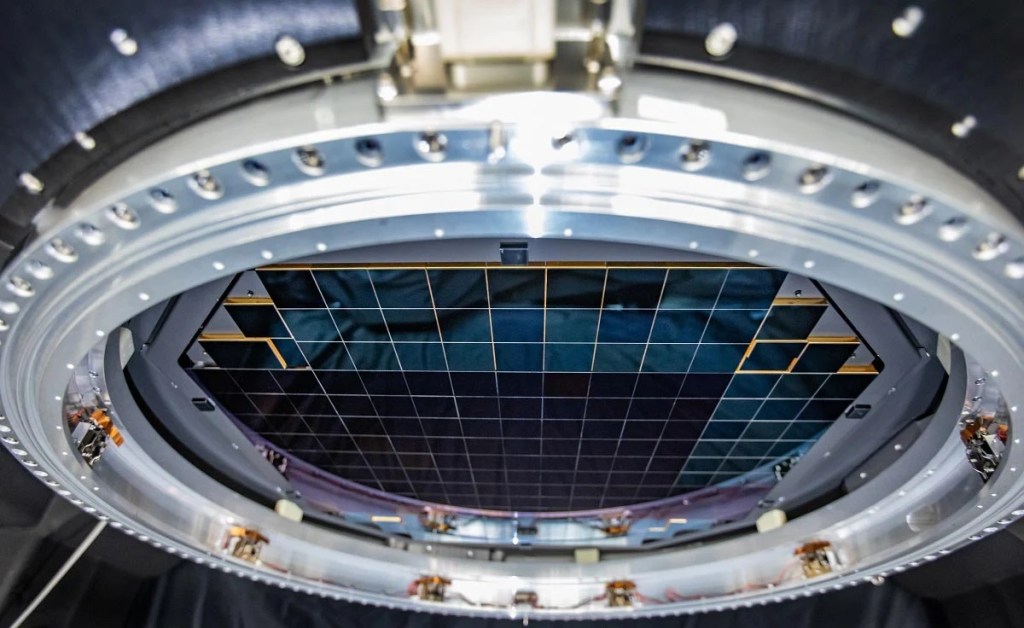

Now fully assembled atop Chile’s Cerro Pachón, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory is beginning its incredible and ambitious mission. Today’s presser focused on unveiling the first images captured by its groundbreaking camera, offering an early glimpse of the observatory’s vast potential. At the heart of the facility is SLAC’s creation: the world’s largest digital camera, a 3.2-gigapixel behemoth developed by the U.S. Department of Energy.

This extraordinary instrument is the central engine of the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), a decade-long sky survey designed to study dark energy, dark matter, and the changing night sky with unprecedented precision and frequency. We are essentially creating a decade-long time-lapse of the universe in detail that has never been captured before, revealing the dynamic cosmos in ways previously impossible. Over the course of ten years, it will catalog 37 billion individual astronomical objects, returning to observe each one every three nights to monitor changes, movements, and events across the sky. I want to learn more about how Artificial Intelligence and machine learning are being brought to bear to help scientists understand what they are seeing.

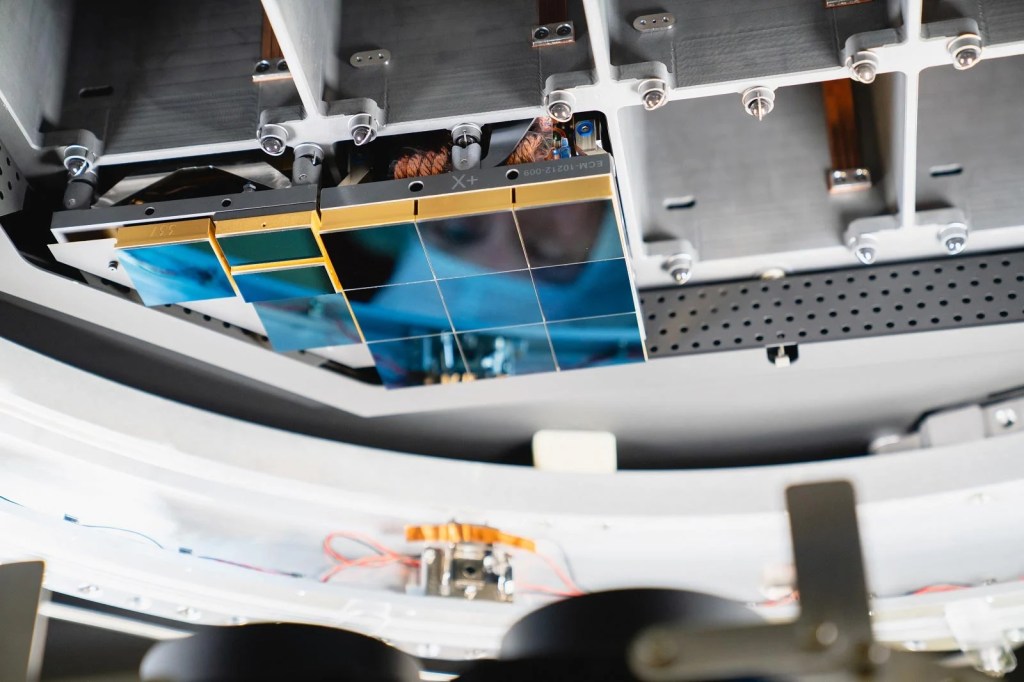

The camera, over 5 feet tall and weighing about three tons, took more than a decade to build. Its focal plane is 64 cm wide-roughly the size of a small coffee table-and consists of 189 custom-designed charge-coupled devices (CCDs) stitched together in a highly precise mosaic. These sensors operate at cryogenic temperatures to reduce noise and can detect the faintest cosmic light, comparable to spotting a candle from thousands of miles away.

Rubin’s camera captures a massive 3.5-degree field of view-more than most telescopes can map in a single shot. That’s about seven times the area of the full moon. Each image takes just 15 seconds to capture and only two seconds to download. A single Rubin image contains roughly as much data as all the words The New York Times has published since 1851. The observatory will generate about 20 terabytes of raw data every night, which will be transmitted via a high-speed 600 Gbps link to processing centers in California, France, and the UK. The data will then be routed through SLAC’s U.S. Data Facility for full analysis.

The images produced will be staggering in both detail and scale. Each exposure will be sharp enough to reveal distant galaxies, supernovae, near-Earth asteroids, and other transient cosmic phenomena in real time. By revisiting the same patches of sky repeatedly, the Rubin Observatory will produce an evolving map of the dynamic universe-something no previous observatory has achieved at this scale.

What sets Rubin apart from even the giants like Hubble or James Webb is its speed, scope, and focus on change over time. Where Hubble peers deeply at narrow regions of space and Webb focuses on the early universe in infrared, Rubin will cast a wide and persistent net, watching the night sky for what moves, vanishes, appears, or explodes. It’s designed not just to look, but to watch. Just imaging the kind of stuff we will see!

This means discoveries won’t just be about what is out there, but what happens out there. Astronomers expect Rubin to vastly expand our knowledge of dark matter by observing how mass distorts space through gravitational lensing. It will also help map dark energy by charting the expansion of the universe with unprecedented precision. Meanwhile, its real-time scanning will act as a planetary defense system, spotting potentially hazardous asteroids headed toward Earth.

But the magic lies in the possibility of the unexpected. Rubin may detect rare cosmic collisions, unknown types of supernovae, or entirely new classes of astronomical phenomena. Over ten years, it’s expected to generate more than 60 petabytes of data-more than any other optical astronomy project to date. Scientists across the globe are already preparing for the data deluge, building machine learning tools to help sift through the torrent of discovery.

And none of it would be possible without SLAC’s camera. A triumph of optics, engineering, and digital sensor technology, the camera is arguably one of the most complex and capable scientific instruments ever built. I don’t care if you’re a Canon or a Sony person, this is way beyond all that. It’s a monument to what happens when curiosity meets collaboration, with California’s innovation engine powering the view.

As first light filters through the Rubin Observatory’s massive mirror and into SLAC’s camera, we are entering a new era of astronomy-one where the universe is not just observed, but filmed, in exquisite, evolving detail. This camera won’t just capture stars. It will reveal how the universe dances.