For over 50 years, the California Coastal Commission has protected public access and natural beauty, but growing challenges—wildfires, housing shortages, and political pressure—are testing its authority like never before.

Having lived for nearly 20 years on the East Coast, I’ve witnessed firsthand how vast stretches of coastline have been heavily developed, often turning pristine shores into exclusive enclaves inaccessible to the general public. In the latter half of the 20th century, America saw a surge in coastal development, driving beachfront property values to unprecedented heights. This boom was accompanied by exclusionary practices from coastal property owners and municipalities, limiting access and reinforcing barriers to the shore. From gated beachfront mansions in the Hamptons to private communities along the Jersey Shore, not to mention the vast development of the coast of Florida (Carl Hiaasen shout out!), many coastal areas are reserved for a privileged few, limiting public access and enjoyment of natural spaces. In stark contrast, California learned from these mistakes early on, adopting a fundamentally different approach focused on keeping its coastline accessible and preserved for everyone.

This ethic of preservation and accessibility has profoundly shaped California’s coastal policies and given rise to institutions specifically tasked with safeguarding the shore. The ethic of preserving California’s coast stretches back more than a century, championed by early conservationists like Julia Platt, a pioneering marine biologist and activist. Platt was a fascinating figure, and we previously covered her story, which you can read here. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Monterey’s coastline was being ravaged by sardine canneries and industrial operations that polluted the bay and threatened marine life. Defying societal barriers, Platt became mayor of Pacific Grove in 1931 and secured public control over the town’s intertidal zones, ensuring their protection from commercial exploitation.

That ethic of appreciation and commitment to coastal preservation remained deeply embedded in California’s identity as the state moved into the 20th century. By the 1970s, this consciousness transformed into action, leading to formal protections that would shape the coastline for generations. Spanning approximately 840 miles from San Diego’s sun-drenched shores to the wild, windswept cliffs of Crescent City, California’s coastline did not remain protected and accessible by accident. It was the result of a concerted effort to safeguard its natural beauty and ensure public access—an effort that culminated in the establishment of the California Coastal Commission, a state agency created to oversee and enforce these critical protections.

The Coastal Commission’s story began in 1972 amid growing environmental awareness and concerns about unchecked development. California residents, alarmed by the threat of losing their treasured coastline to developers, launched grassroots campaigns resulting in Proposition 20—the Coastal Initiative. This public referendum created the Coastal Commission initially as a temporary regulatory body.

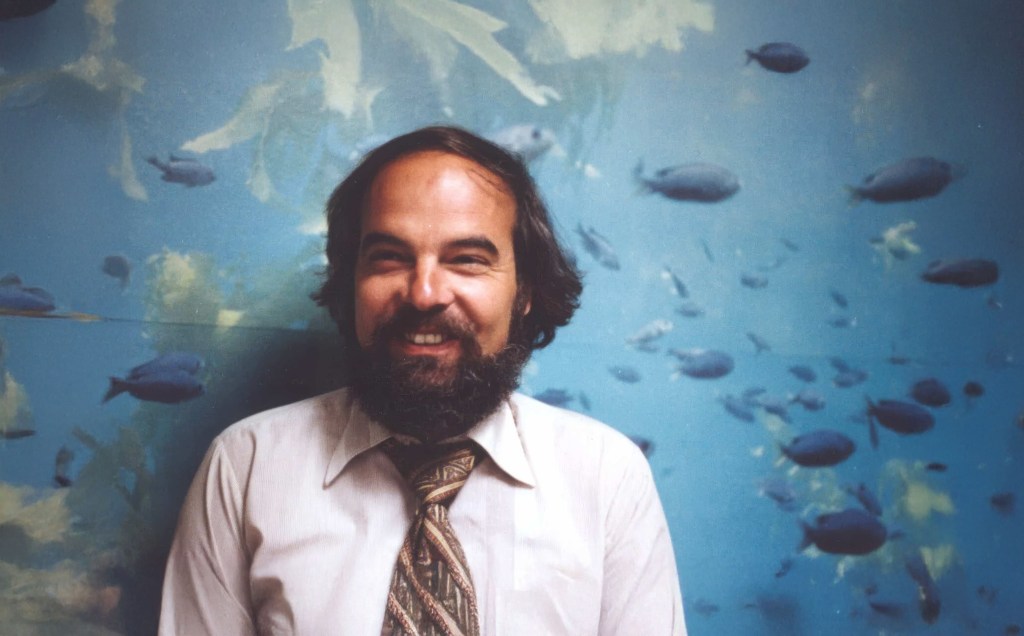

In 1976, recognizing the importance of long-term coastal preservation, the California Legislature passed the Coastal Act, permanently institutionalizing the Coastal Commission and its values (values shared by a majority of Californians, I should add). Key legislative figures included Assemblymember Alan Sieroty and Senator Jerry Smith. Peter Douglas, a passionate advocate for environmental justice who later became the Commission’s long-serving Executive Director, was instrumental in drafting the Coastal Act. Born in Berlin and fleeing Nazi Germany during World War II, Douglas’s personal experiences deeply influenced his dedication to environmental protection. One of his most lasting statements about the coast is, “The coast is never saved, it is always being saved.” (Makes for a good T-shirt.)

(University of California, Berkeley)

Under Douglas’s leadership, which spanned from 1985 until his retirement in 2011, the Coastal Commission achieved significant conservation victories. One landmark success was securing public access to Malibu’s Broad Beach in 1981, previously restricted to wealthy homeowners (many of them famous celebrities). Similarly, the Commission prevented extensive development of Orange County’s Bolsa Chica Wetlands, preserving this crucial ecological habitat and protecting numerous bird and marine species. Also in Orange County, the historic cottages at Crystal Cove State Park were preserved as affordable accommodations rather than being transformed into a luxury resort. Douglas was tenacious and stubborn in his efforts to protect the coast. He was “the world’s best bureaucratic street fighter,” according to Steve Blank, a member of the commission, who spoke to The New York Times in 2010.

Perhaps the Commission’s most publicized battle was with billionaire Vinod Khosla over Martins Beach near Half Moon Bay. After purchasing land surrounding the beach in 2008, Khosla closed the access road, igniting a lengthy legal fight. The Commission, alongside advocacy groups, successfully argued that public beach access must be maintained, culminating in court decisions mandating the reopening of Martins Beach to the public. It was a significant affirmation of the public’s coastal rights.

Khosla became something of a vilified figure, perhaps for a good reason. As of March 2025, the legal dispute over public access to Martins Beach continues. In May 2024, San Mateo County Superior Court Judge Raymond Swope ruled that the lawsuit filed by the California State Lands Commission and the California Coastal Commission against Khosla could proceed. The state agencies argue that, based on the public’s longstanding use of the beach, access should remain open under the legal doctrine of implied dedication.

Beyond these high-profile victories, the Commission diligently protects scenic coastal views by regulating construction along vulnerable bluffs, safeguarding habitats for endangered species like the California least tern and the Western snowy plover. The significance of this protection extends far beyond simply claiming a spot on the sand or catching a wave. The California coast is a global treasure trove of biodiversity, shaped by the collision of cold and warm ocean currents, rugged geology, and an array of microclimates. Its kelp forests, some of the most productive ecosystems on Earth, form towering underwater cathedrals that shelter fish, sea otters, and invertebrates while sequestering carbon and buffering coastal erosion. Tide pools teem with anemones, sea stars, and scuttling crabs, while offshore waters host migrating gray whales, pods of orcas, and dolphin super pods. Few places on Earth does such a dramatic convergence of oceanic and terrestrial life create a living laboratory as dynamic, fragile, and irreplaceable as California’s coastline.

Safeguarding these resources has always been a core part of the Coastal Commission’s mission. Yet, the Commission’s broad regulatory authority hasn’t been without controversy (understatement alert!). In fact, there’s been a lot over the years, and in particular right now. Critics argue it often overreaches, impacting private property rights and overriding local governance. Property owners have faced severe challenges due to stringent permit requirements and mandatory easements for public access. Furthermore, vast amounts of red tape have often contributed to delays and higher costs, fueling tension between environmental protection and economic development, particularly in the context of California’s ongoing housing crisis. The commission’s plans for managed retreat in response to coastal erosion have sparked ongoing concern among coastal property owners.

Jeff Jennings, the mayor of Malibu commented: “The commission basically tells us what to do, and we’re expected to do it. And in many cases that extends down to the smallest details imaginable, like what color you paint your houses, what kind of light bulbs you can use in certain places.

The challenges of balancing conservation with development have become even more urgent in the face of devastating wildfires, such as the Palisades Fire. This historically destructive blaze burned numerous homes along the coast, leaving behind not only physical devastation but also a complex and expensive rebuilding process. Restoring these communities requires immense resources, regulatory approvals, and long-term planning, raising questions about whether the Coastal Commission is up to the task.

Even Governor Gavin Newsom has been critical of the Commission, citing delays and bureaucracy that may hinder swift rebuilding efforts. The ongoing tension between preserving the natural environment and addressing the needs of displaced residents continues to test the Commission’s authority and effectiveness. Before dismantling the Commission and stripping it of its authority as the guardian of the coast, we must ask ourselves what it would mean to lose an agency that has stood for public access, environmental protection, and coastal preservation for over 50 years. The consequences of weakening its influence could reshape California’s coastline in ways that future generations may come to regret.

The California Coastal Commission has 12 voting members and 3 non-voting members, appointed by the Governor, the Speaker of the Assembly, and the Senate Rules Committee. Six of these are locally elected officials, and six are public members. They are supported by key figures like Executive Director Kate Huckelbridge (the first woman to lead the California Coastal Commission in its 50-year history) and Chair Justin Cummings. However, the Commission now faces mounting pressure as it navigates growing criticism over its efficiency and decision-making. Some argue that the Commission has become too rigid, impeding much-needed development, while others warn that weakening its authority would open the door to rampant privatization and environmental degradation. Surely, there is a middle ground?

But before dismantling an institution that has served as California’s coastal safeguard for over five decades, we must fully understand what is at stake. The California Coastal Commission has played a crucial role in preserving public access, protecting natural habitats, and maintaining the scenic beauty of the shoreline. Its legacy is visible in the open beaches, thriving wetlands, and untouched bluffs that define the state’s coastline. Stripping away its influence could have lasting consequences, reshaping California’s shorelines in ways that future generations may find irreversible and regrettable. Changes to the Commission’s authority may be necessary, at least temporarily, to expedite rebuilding efforts for those who have lost their homes. However, we must be cautious about how much power is stripped away, ensuring that any reforms do not undermine the very protections that have kept California’s coast open and preserved for decades.