How the 1969 Penrose Conference on plate tectonics at Asilomar in California transformed our understanding of Earth’s dynamic processes.

Before the late 1960s, understanding Earth’s shifting surface, particularly in a geologically active region like California, was a major scientific challenge. For most of human history, the causes of earthquakes remained an enigma—mysterious and terrifying, often attributed to supernatural forces. In Japan, for example, earthquakes were traditionally believed to be caused by Namazu, a giant catfish said to live beneath the earth and whose thrashing would shake the land. Many societies believed earthquakes were divine punishments or omens, while others considered them an essential part of creation, events necessary to form a world habitable by us humans.

The complexity of California’s landscape, its mountains, valleys, deserts, and intricate network of faults, posed difficulties for early geologists. The land appeared chaotically interwoven, with many different types of rock making up the gaping deserts and soaring peaks. As the great University of California at Davis geologist Eldridge Moores once put it, “Nature is messy. Don’t expect it to be uniform and consistent.”

But there was no overarching explanation for how these earthly features got there. Scientists could observe and record earthquakes, but without a unifying theory, they struggled to piece together the deeper mechanisms driving these powerful events.

This frustration lingered until the late 1960s when an intellectual revolution in geology took shape. Despite the dawn of the space age and the rise of computing power, many earth scientists still clung to the belief that the continents were fixed, immovable features on the Earth’s surface. The breakthrough came with the acceptance of plate tectonics—a theory that elegantly explained not just earthquakes, but the entire dynamic nature of Earth’s surface. And for many geologists, the moment this new understanding solidified was in December 1969, at a groundbreaking conference at the Asilomar Conference Center in California that reshaped the future of the field. (Notably, Asilomar was also the site of the historic 1975 conference on recombinant DNA, where scientists gathered to establish ethical guidelines for genetic research, an event we have explored previously.) This was the moment when plate tectonics, a concept that would fundamentally reshape our view of the planet, truly took hold in the Western American geological community.

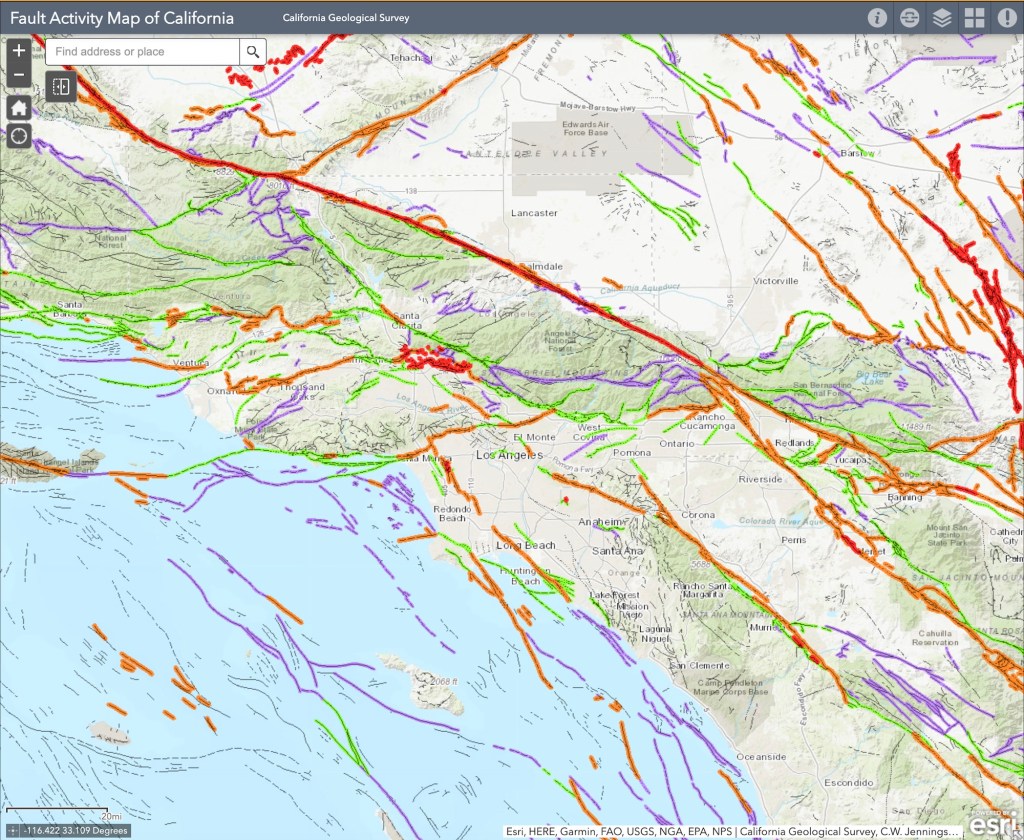

For centuries, explanations for Earth’s features ranged from catastrophic events to gradual uplift and erosion, a debate that became known as uniformitarianism versus catastrophism. In California, the sheer complexity of the geology, with its links go far beyond the borders of the state, hinted at powerful forces at play. Scientists grappled with the origins of the Sierra Nevada, the formation of the Central Valley, and the persistent threat of earthquakes along the now-famous San Andreas Fault. The prevailing models, however, lacked the comprehensive framework to connect these disparate observations into a coherent narrative.

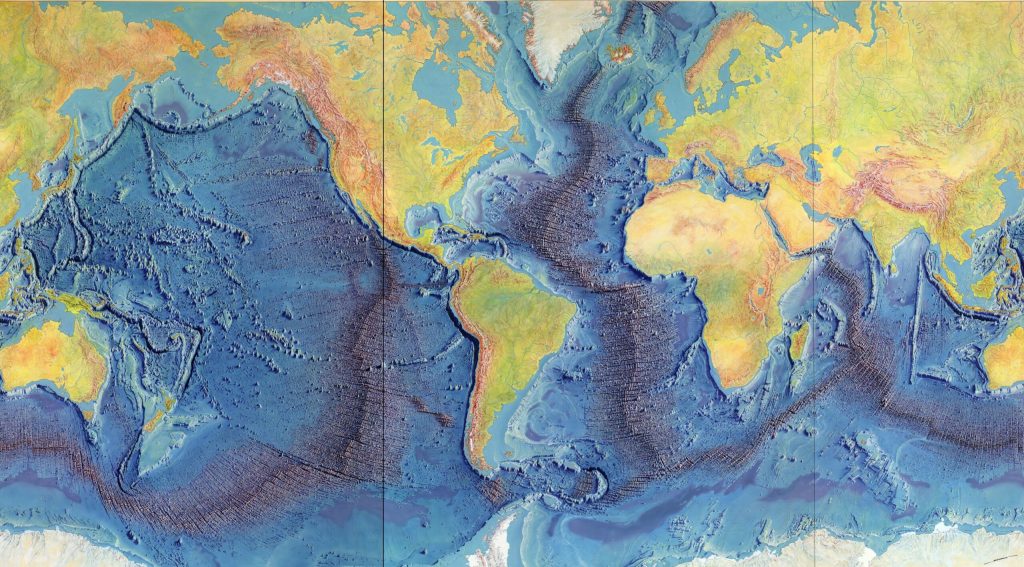

The seeds of the plate tectonic revolution had been sown earlier in the 20th century with Alfred Wegener’s theory of continental drift. Anyone looking at a world map or globe could see how the coastlines of certain continents, particularly South America and Africa, seemed to fit together like pieces of a puzzle, suggesting they were once joined. Wegener proposed that the continents were once joined together in a supercontinent called Pangaea and had gradually drifted apart over millions of years. While his ideas were initially met with skepticism, particularly regarding the mechanism that could drive such massive movements, compelling evidence from paleontology, glacial geology, and the jigsaw-like fit of continental coastlines slowly began to sway opinions. The discovery of seafloor spreading in the 1960s (itself a great story, featuring the brilliant geologist and cartographer Marie Tharp) which revealed that new oceanic crust was constantly being generated at mid-ocean ridges and that the ocean floor itself was moving like a conveyor belt, provided the crucial mechanism Wegener lacked.

It was against this backdrop of burgeoning evidence that the Geological Society of America convened one of its annual Penrose Conferences in December 1969 at the Asilomar Conference Center in Pacific Grove, California. Titled “The Meaning of the New Global Tectonics,” the event drew structural geologists from all over the world. The geological world changed overnight. A key figure in the conference was William R. Dickinson, a leading structural geologist whose work helped bridge the gap between traditional geological interpretations and the emerging plate tectonic framework. Dickinson’s research on sedimentary basins and tectonic evolution provided critical insights into how plate movements shaped the western United States, further solidifying the new theory’s acceptance.

These conferences were designed to be intimate gatherings where geologists could engage in focused discussions on cutting-edge research. The 1969 meeting proved to be a pivotal one. As UC Davis’ Moores, then a youthful figure who would become a leading voice of the “New Geology” in the West, later wrote, “the full import of the plate tectonic revolution burst on the participants like a dam failure”.

(Photo: Erik Olsen)

Paper after paper presented at the conference demonstrated how the seemingly simple notion of large plates floating atop the Earth’s plastic mantle (the asthenosphere) could explain a vast array of geological phenomena. The location of volcanoes, the folding of mountains (orogeny), the distribution of earthquakes, the shape of the continents, and the history of the oceans all suddenly found a compelling and unified explanation within the framework of plate tectonics. Geologist John Tuzo Wilson famously referred to plate tectonics as ‘the dance of the continents,’ a phrase that captured the excitement and transformative nature of this intellectual breakthrough.

For Moores, the conference was a moment of profound realization. “It was a very exciting time. I still get goosebumps even talking about it,” he told the writer John McPhee. “A turning point, I think it was, in the plate tectonic revolution, that was the watershed of geology.” Moores had been contemplating the perplexing presence of ophiolite sequences – distinctive rock assemblages consisting of serpentines, gabbro/lava, and sediments – found high in the mountains of the West, including California. He suddenly grasped that these strange and “exotic” rock sequences were remnants of ancient ocean floors that had been lifted on top of the continent through the collision of tectonic plates.

Moores reasoned that the serpentines and coarsely crystalline igneous rocks at the base of these sequences were characteristic of the rocks underlying all the world’s oceans. The “green rocks” in the middle (now the state rock of California) showed evidence of moderate pressure and temperatures, indicating they had been subjected to significant geological forces. By connecting these ophiolite sequences to the processes of plate collision and obduction (where one plate rides over another), Moores provided a powerful piece of evidence for plate tectonics and offered a new lens through which to understand the complex geological architecture of the American West.

His deduction was in line with what is now known about plate tectonics. The geological “confusion” apparent in the Rockies, the Sierra Nevada, and other western mountain chains was now understood as the result of neighboring plates bumping into each other repeatedly over vast geological timescales. The concept of terranes, foreign rock slabs or slices or sequences that have traveled vast distances and become accreted to continents, further illustrated the dynamic and assembly-like nature of California’s geological landscape.

)

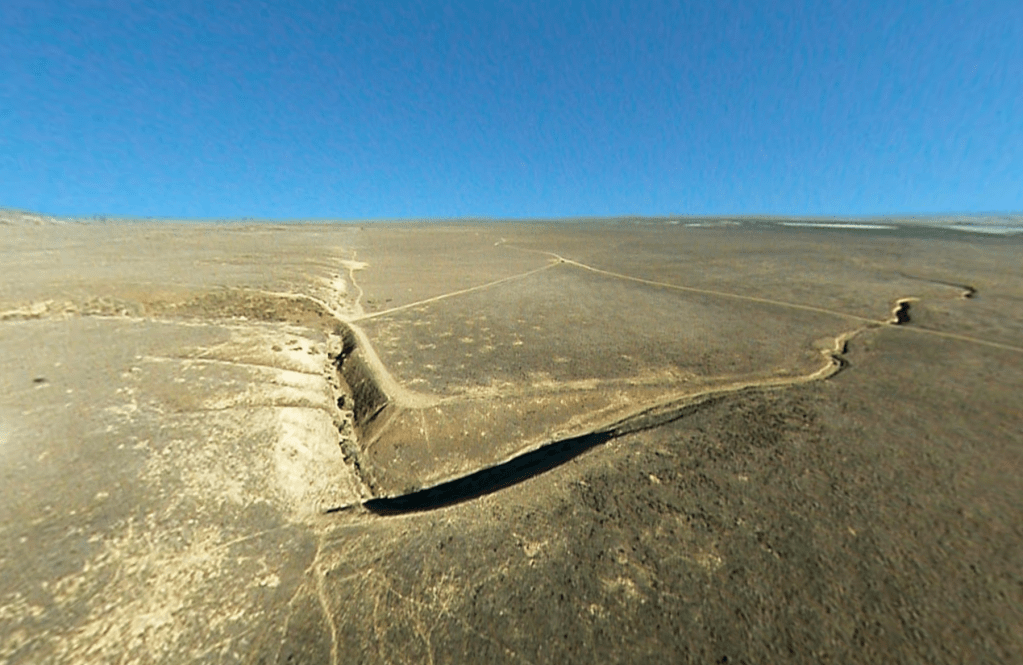

California, situated at the active boundary between the massive Pacific Plate and the North American Plate, became a prime natural laboratory for studying the principles of plate tectonics. The San Andreas Fault, a “right-lateral strike-slip fault” where the Pacific Plate slides northward relative to the North American Plate, is a direct consequence of this ongoing tectonic interaction. Places like Parkfield, California, lying directly on the fault, became the center of the seismic universe, offering invaluable opportunities to study the processes of locking and unlocking that precede earthquakes.

The dramatic offsets of streams like Wallace Creek on the Carrizo Plain vividly demonstrate the horizontal movement along the fault. These offsets, where streams appear abruptly displaced, serve as clear, visual records of the fault’s slip history, showing just how much the land has shifted over time. Further proof of the movement of plates along the fault was uncovered in a remarkable investigation by Thomas Dibblee Jr., a pioneering field geologist who meticulously mapped vast regions of California. One of his most compelling discoveries was the striking geological similarity between rocks found at Pinnacles National Park and those in the Neenach Volcanic Field, located more than 195 miles to the southeast. Dibblee determined that these formations were once part of the same volcanic complex but had been separated by the gradual (but pretty damn quick in geological time) movement of the Pacific Plate along the San Andreas Fault over millions of years.

The insights gained from the plate tectonic revolution, sparked in part by that pivotal conference in Pacific Grove, continue to inform our understanding of California’s geological hazards and history. The work of scientists like Eldridge Moores and the subsequent advancements in the field have provided a robust framework for interpreting the state’s complex and ever-evolving landscape. The 1969 Penrose Conference marked not just a shift in scientific thinking but a fundamental unlocking of some of the Earth’s deep secrets, with California the place, once again, at the center of scientific advance.