Pinnacles National Park’s open landscape of dramatic rock formations and craggy spires looks otherworldly, especially in golden hour light. But few people who visit the park, located in Central California, southeast of the San Francisco Bay Area, are aware that the rock formations were once at the center of a fierce debate in the history of California geology.

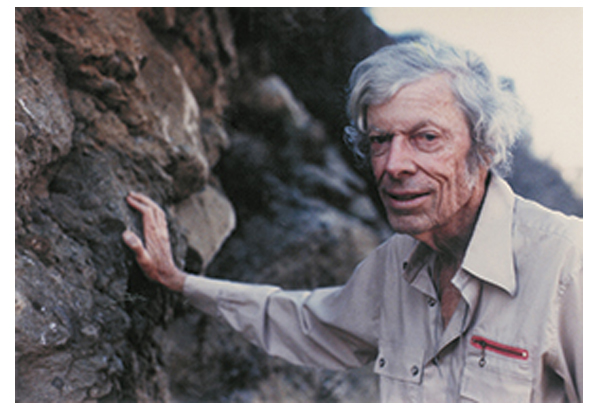

And at the center of the controversy was a young geologist named Thomas Dibblee Jr.

Pinnacles National Park, formerly Pinnacles National Monument, tells the story of ancient volcanic activity and the relentless geologic forces of the San Andreas Fault. This fault, a major boundary between the Pacific and North American tectonic plates, is the platform for the dramatic northward journey of the park’s volcanic remnants. Dibblee’s research illuminated how, over millions of years, the landscapes we see today were sculpted by the movements of these tectonic plates and how the shape of California as a state has changed dramatically as a result.

The crux of Dibblee’s discovery lies in the relationship between Pinnacles National Park and a volcanic source located near present-day Neenach, close to Palmdale in Southern California. The geological narrative that Dibblee pieced together revealed that the rock formations at Pinnacles originated from volcanic eruptions that occurred approximately 23 million years ago, near what is now Neenach. Over millions of years, the relentless movement along the San Andreas Fault has transported these formations over 195 miles (314 kilometers) to their current location. At the time, very few people, geologists included, believed that was possible.

Purchase stunning coffee mugs and art prints of iconic California scenes.

Check out our Etsy store.

Dibblee had to be wrong. But it turned out, he was not, and his measurements and discovery launched a passionate debate about the speed of geologic forces.

Dibblee’s findings not only shed light on the significant distances that landscapes can travel over geological timeframes but also provided a tangible connection between the theory of plate tectonics and observable geological features. The juxtaposition of Pinnacles National Park and the Neenach volcanic formation serves as a clear indicator of the San Andreas Fault’s role in shaping California’s geological, indeed it’s physical, identity.

A key aspect of Dibblee’s methodology was his keen observational skills, which enabled him to recognize that the rocks at Pinnacles National Park were strikingly similar in composition and age to those near Neenach, even though these areas are separated by about 195 miles (314 kilometers) today. He noted the volcanic origins of these formations and, through detailed mapping, was able to correlate specific rock types and strata between these distant locations.

Another crucial element in Dibblee’s discovery was his understanding of the San Andreas Fault as a major geological feature capable of significant lateral movement (remember the San Andreas is a slip or sliding fault). By correlating the age and type of rocks across this fault line, Dibblee inferred that the only plausible explanation for the similarity between the rocks at Pinnacles and those near Neenach was that they had once been part of the same volcanic field, which had been split and displaced over millions of years due to the movement of the San Andreas Fault.

Dibblee’s work also benefited from the broader scientific context of his time, particularly the emerging theory of plate tectonics in the mid-20th century. This theoretical framework provided a mechanism for understanding how large-scale movements of the Earth’s crust could result in the displacement of geological formations over vast distances. Dibblee’s findings at Pinnacles and Neenach became a compelling piece of evidence supporting the theory of plate tectonics, showcasing the San Andreas Fault’s role in shaping California’s landscape.

But Dibblee’s ideas were controversial at the time. Many in the scientific community were hesitant to embrace a theory that suggested such dramatic movement across the Earth’s crust, partly because it challenged existing paradigms and partly due to the limitations of the geological evidence available at the time. The prevailing theories favored more static models of the earth’s crust, with changes occurring slowly over immense periods. Dibblee’s insights into tectonic movements and the geological history of regions like the Pinnacles National Park were ahead of their time and laid the groundwork for the acceptance of plate tectonics.

This Pinnacles revelation was groundbreaking, emphasizing the dynamic and ever-changing nature of the Earth’s surface. Dibblee’s ability to piece together these monumental shifts in the Earth’s crust from his detailed maps and observations has left a lasting impact on our understanding of geological processes. His work at Pinnacles and the recognition of its journey alongside the San Andreas Fault underscores the importance of detailed geological mapping in unraveling the Earth’s complex history.

Born in 1911 in Santa Barbara, California, Dibblee’s life and work were deeply intertwined with the rugged terrains and picturesque landscapes of the Golden State, Dibblee’s journey into geology began at a young age, fostered by his natural curiosity and the geological richness of his native state.

After earning his degree from Stanford in 1936, Dibblee embarked on his professional journey with Union Oil, later moving to Richfield. It was during this period that his extensive field mapping efforts culminated in the discovery of the Russell Ranch oil field near New Cuyama. By 1952, Dibblee had meticulously mapped every sedimentary basin in California with potential for oil, cementing his legendary status as a petroleum geologist. His reputation for traversing the state’s backcountry on foot for extended weeks became a defining aspect of his character and contributed to his storied career in geology.

Dibblee moved on to a career at the United States Geological Survey (USGS) that would span over six decades, much of it spent with the agency and then later through independent projects. His work ethic and passion for fieldwork were unparalleled; Dibblee was known for his meticulous and comprehensive approach, often spending long days in the field, mapping out California’s complex strata with precision and care.

Over his career, Dibblee mapped over 240,000 square kilometers of California’s terrain, an achievement that provided an invaluable resource for understanding the state’s geological history and structure. He mapped large swaths of the Mojave Desert, the Coast Range and the Los Padres National Forest, earning a presidential volunteer action award in 1983 from President Reagan.

His maps are celebrated for their accuracy and detail, serving as critical tools for academic research, oil exploration, environmental planning, and education. The Dibblee Geological Foundation, established to honor his work, continues to publish these maps, ensuring that his legacy lives on.

Dibblee’s insights into the geology of California were pivotal in several areas, including the understanding of the San Andreas Fault, a major fault line that has been the focus of extensive seismic research due to its potential for large earthquakes. Dibblee’s mapping efforts helped to clarify the fault’s characteristics and behavior, contributing to our understanding of earthquake risks in California and aiding in the development of safer building practices and disaster preparedness strategies.

Furthermore, Dibblee’s work shed light on the process of plate tectonics and the geological history of the western United States. His observations and mapping of sedimentary formations and fault systems in California provided empirical evidence that supported the theory of plate tectonics, a cornerstone of modern geology that explains the movement of the Earth’s lithospheric plates and the formation of various geological features.

Thomas Dibblee Jr.’s contributions to the field of geology are not just confined to his maps and scientific discoveries. He was also a mentor and inspiration to many aspiring geologists, sharing his knowledge and passion for the Earth’s history through lectures, field trips, and personal guidance. His dedication to his work and his ability to convey complex geological concepts in an accessible manner made him a respected figure among his peers and students alike. Through his dedication and pioneering work, Dibblee has left an indelible mark on the field of geology, making him a true giant in the scientific exploration of California as well as our planet.