California’s coast is home to dozens of seamounts, each harboring diverse ecosystems and geological mysteries waiting to be explored.

If you’ve ever looked out at the vastness of the ocean, you might think it’s a uniformly barren and flat landscape below the tranquil or tempestuous waves. But you’d be mistaken. Imagine for a moment a hidden world of underwater mountains, volcanoes that never broke the water’s surface, all lying in the mysterious depths of the ocean. These enigmatic formations are known as seamounts, and off the coast of California, they constitute an environment as fascinating as it is vital.

Interestingly, a lot of these seamounts off California are actually relatively new to science. According to Robert Kunzig and his book Mapping the Deep: “In 1984, a sidescan survey off southern California revealed a hundred uncharted seamounts, or undersea volcanoes, in a region that had been thought to be flat.”

The genesis of these structures begins with a geologic process known as plate tectonics. As tectonic plates move beneath the Earth’s crust, they create hotspots of molten rock. This magma escapes through weak points in the crust and solidifies as it reaches the cold seawater, gradually building up into an undersea mountain. After thousands of years, a seamount is born. Most of California’s seamounts are conical in shape, though erosion and other geological forces can turn them into more complex formations over time.

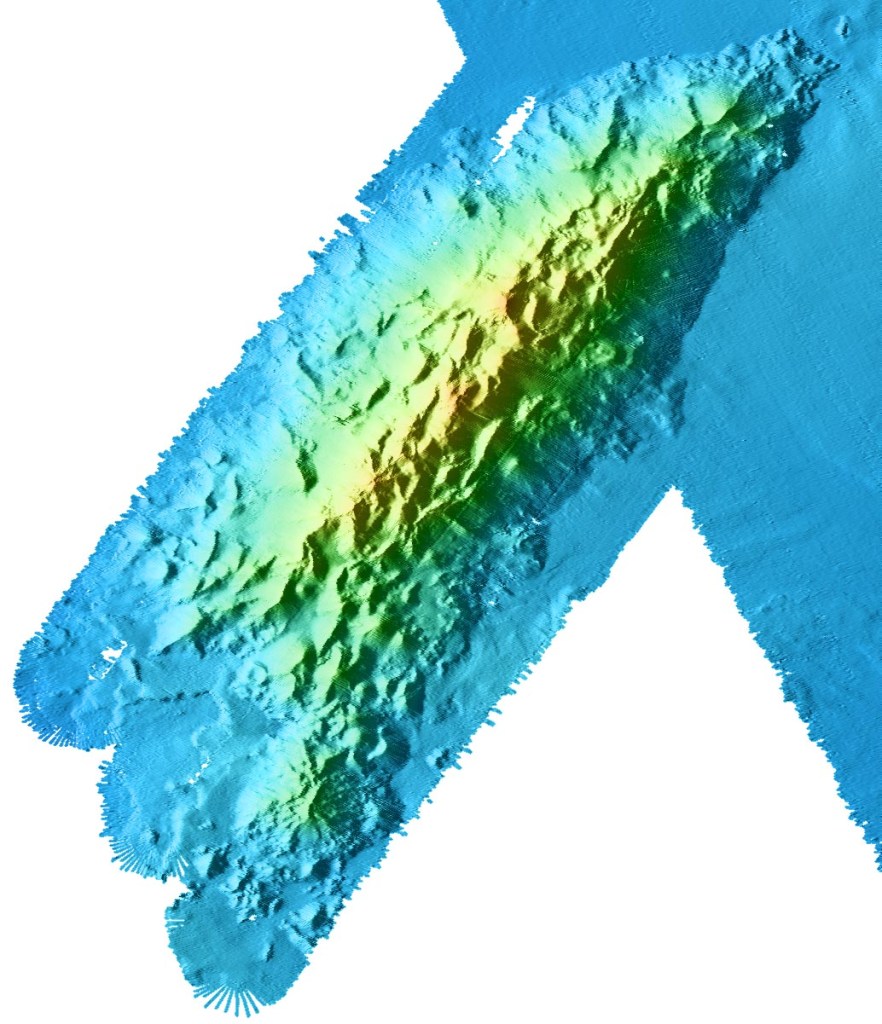

Each seamount is a world unto itself, with distinct mineral compositions, shapes, and ecosystems. Recent research has energized the scientific community. For instance, the Davidson Seamount is the most well-known of these volcanoes and was the first underwater peak to be named a seamount. The seamount is named for George Davidson, a British pioneering scientist and surveyor. Located about 80 km (50 miles) off the coast of Big Sur, it’s shaped like an elongated arrowhead made up of several parallel ridges of sheer volcanic cones. Most of these erupted about 10-15 million years ago, and are made up 320 cubic km of hawaiite, mugearite, and alkalic basalt, the basalt types commonly found along spreading ridges like the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

The sheer number of seamounts only began to emerge when new detection methods were developed, including the ability to spot them from space. These underwater mountains are so massive that they create a gravitational pull, drawing seawater slightly toward their center of mass, much like the moon’s pull generates tides. Since seawater is incompressible, it doesn’t compress around the seamounts but instead forms slight bulges on the ocean surface. Satellites can detect these bulges, helping locate the hidden, basaltic peaks below. Satellite studies suggest that the largest seamounts—those over 5,000 feet—may number anywhere from thirty thousand to over one hundred thousand worldwide, with high concentrations in the central Pacific, Indian, and Atlantic Oceans, around Antarctica, and in the Mediterranean. Each of these seamounts is an underwater volcano, typically lining mid-ocean ridges, subduction zones, or one of the forty to fifty oceanic hot spots where the earth’s crust is thin and magma rises from the mantle.

Davidson Seamount is by far the best-studied of the many seamounts off the California coast. Stretching a sprawling 26 miles in length and spanning 8 miles across, this colossal seamount ranks among the largest known formations of its kind in U.S. territorial waters. Towering at a remarkable 7,480 feet from its base to its peak, the mountain remains shrouded in the depths, with its summit situated a substantial 4,101 feet beneath the ocean’s surface. Studies have indicated that some seamounts contain deposits of rare earth elements, which could have potential economic importance in the future.

Seamounts are biodiversity hotspots. Boasting an incredibly diverse range of deep-sea corals, Davidson Seamount serves as a kind of underwater Eden. Often referred to as “An Oasis in the Deep,” this submerged mountain is a bustling metropolis of marine life, featuring expansive coral forests and sprawling sponge fields. But it doesn’t stop there—crabs, deep-sea fishes, shrimp, basket stars, and a host of rare and still-unidentified bottom-dwelling creatures also call this place home. The seamount is more than just a biologically rich environment; it’s a treasure trove of national importance for its contributions to ocean conservation, scientific research, education, aesthetics, and even history.

Perhaps the most astonishing discovery at Davidson Seamount occurred in 2018, when scientists discovered the “Octopus Garden,” the largest known aggregation of octopuses in the world. The garden is about two miles deep and was discovered by researchers on the research vessel (RV) Nautilus. The team of scientists initially spotted a pair of octopuses through a camera on a remotely operated vehicle (ROV). Amanda Kahn, an ecologist at Moss Landing Marine Laboratories and San Jose State University, who was on the Nautilus during the discovery, told Scientific American that after observing the pair for a bit, the operators started to drift away from the rocks to move on, but immediately saw something unusual. “Up ahead of us were streams of 20 or more octopuses nestled in crevices,” Kahn says.

Typically lone wanderers of the ocean, octopuses aren’t known for their social gatherings. So, when researchers stumbled upon more than just one or two of these creatures, they knew something out of the ordinary was afoot. Swiftly pivoting from their original plans, the team zeroed in for a closer look. What they found was a community of these grapefruit-sized, opalescent octopuses, along with something even more mysterious—unusual shimmers in the surrounding water, hinting at the existence of some kind of underwater fluid seeps or springs. It turns out the octopuses migrate to deep-sea hydrothermal springs to breed. The females brood their eggs in the garden, where it is warmer than surrounding waters.

“This Octopus Garden is by far the largest aggregate of octopuses known anywhere in the world, deep-sea or not,” James Barry, a benthic ecologist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute told Scientific American. Barry is the leader of the new study, published on in August in Science Advances, that reveals why the animals are gathering. The researchers have observed over 5,700 Pearl octopuses (Muusoctopus robustus) breeding near Davidson Seamount, 3,200 meters below the ocean’s surface. In this deep-sea nursery, octopus mothers keep their eggs warm in 5°C waters flowing from a hydrothermal spring. The water is more than 3°C warmer than the surrounding ocean. This added warmth accelerates the embryos’ development, allowing them to fully mature in just under two years on average.

The Octopuses Garden was studied over the course of 14 dives with MBARI’s remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Doc Ricketts. It is within the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, so it is federally protected against exploitation and extraction., although many scientists are concerned that global warming could end up having a deleterious impact on the biological life found around seamounts.

So far scientists have discovered other octopus gardens around the globe. There are four deep-sea octopus gardens in total. Two are located off the coast of Central California and two are off the coast of Costa Rica.

New technological advancements like Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs) have recently opened doors to discoveries we never thought possible. Cutting-edge imaging technology has finally given us the ability to capture strikingly clear and high-resolution pictures from this enigmatic deep-sea habitat. These vivid images provide both the scientific community and the general public with unprecedented peeks into the lives of rare marine species inhabiting this mostly cold and dark underwater world.

Davidson Seamount’s proximity to the rich educational and research ecosystem in the Monterey Bay area. One of the world’s preeminent ocean research organizations, the Monterey Bay Research Institute (MBARI), is located in Moss Landing, California, right at the spot where the magnificent Monterey Canyon stretches away from the coast for hundreds of miles. This geographic boon makes it easier for interdisciplinary teams to join forces, enriching our understanding and educational outreach related to this uniquely captivating undersea landscape.

Beyond being hubs of biodiversity, seamounts also serve as waypoints for migratory species. Just like rest stops along a highway, these underwater mountains provide food and shelter for creatures like whales and tuna on their long journeys. This makes seamounts critical for the health of global marine ecosystems. Additionally, understanding seamounts could give us insights into climate change. They play a role in ocean circulation patterns, which, in turn, affect global weather systems. They are also excellent “archives” of long-term climate data, which could help us understand past climate variations and predict future trends.

Advances in underwater technology, like ROVs, autonomous submersibles and better remote sensing methods, are making it easier to study these mysterious mountains. But many questions still remain unanswered. For instance, how exactly do seamount ecosystems interact with surrounding marine environments? What are the long-term impacts of human activities, like deep-sea mining or overfishing, on these fragile habitats? And what untapped resources, both biological and mineral, lie waiting in these submerged summits?

Octopus Garden between research expeditions. (Photo: MBARI)

We can wax poetic about the mysteries of seamounts, but understanding them better is crucial for the preservation of marine ecosystems and for equipping ourselves with the knowledge to tackle environmental challenges. So, the next time you look out over the ocean, consider the hidden worlds lying beneath those waves—each a bustling metropolis of life and a potential goldmine of scientific discovery.

More information:

Video about California seamounts

Recent discovery of the Octopuses garden (MBARI).

.